The cuckoo holds a special place in Irish folklore, serving as a weather forecaster, predictor of farming fortunes, and harbinger of good and bad luck. The dwindling numbers of cuckoos visiting Ireland highlight the urgent need to not only conserve the bird species but also to preserve its rich associated lore.

The cuckoo – “an cuach” in Irish – features prominently in various old sayings, superstitions and tales from Ireland. They mainly revolve around the recurring and intertwined themes of the changing of seasons, weather predictions, farming and luck. The Irish Folklore Commission recorded a wealth of cuckoo-related lore in the first half of the 20th century, with the bird featuring heavily within the Schools’ Collection (1937–39) in particular.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Seasons, weather and farming predictions

The arrival of the common cuckoo (“Cuculus canorus“), with its distinctive call, is always welcomed as a signal for the beginning of summer in Ireland. The following old verse and similar renditions have long been recited throughout Ireland and Britain:

“The cuckoo comes in April.

She sings her song in May,

Then in June another tune,

And in July she flies away.”

In Donegal, anything out of the ordinary was called a “winter cuckoo”.

As we all know, the cuckoo doesn’t build its own nest or rear its young; rather, she lays her eggs in the nests of other birds. In Ireland, the unwitting host is often the meadow pipit, usually known in Irish as “riabhóg mhóna” but also as “banaltra na cuaiche” (meaning “the cuckoo’s nurse”) or “giolla na cuaiche” (meaning “the cuckoo’s servant”). The pipit was also called the “ground lark” in certain parts of Ireland.

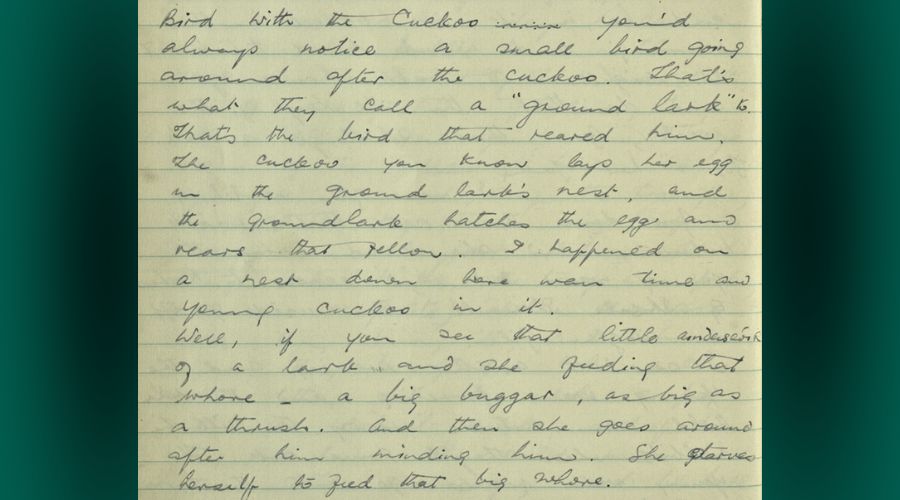

After the young cuckoo hatches, it rolls the other eggs out of the nest, securing its place as the sole surviving “gearrcach” (“chick”). Its unfortunate foster mother then wears herself out feeding the hungry young bird. John Carroll from Co. Wexford in 1937/38 explained:

“You’d always notice a small bird going around after the cuckoo. That’s what they call a ‘ground lark’ … That’s the bird that reared him.”

Though we all delight in hearing the cuckoo’s first call every year, its arrival can herald a harsh and bitter spell of weather known as “Scairbhín na gCuach” (meaning the rough weather of the cuckoo), which usually lasts from mid-April to mid-May. In Britain, this is sometimes referred to as a “gowk storm” (gowk being another name for the cuckoo). On the other hand, in Clonmacnoise, Co. Offaly, there was a belief that when the cuckoo sings at night, it signals fine weather.

Sign up to our newsletter

Another well-known cuckoo saying in Ireland seems to caution against staying up late at night: “Cuckoo oats and woodcock hay, up all night and down all day”.

However, a similar rhyme, known in Scotland, was recorded by James Hardy in 1879: “Cuckoo oats and woodcock hay, make a farmer run away”. This, Hardy explained, means that if adverse weather in spring prevents the sowing of oats until the cuckoo is heard or if heavy autumn rains prevent the gathering of the last of the hay until after the arrival of the woodcock, both circumstances will lead to substantial losses for the farmer. It may also warn against laziness and delaying tasks. Even today, in some parts of Ireland, a farmer who postpones sowing his crops might be labelled a “cuckoo farmer”.

>>> YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: The heron in Irish folklore

If you happen to hear the cuckoo’s call while you’re planting potatoes, you can expect to find what are known as “cuckoo potatoes” later in the year, implying a poor crop. This Irish sean-fhocal (old saying) also links the cuckoo with a bad harvest:

“Má labhruigheann an chuach ar crann gan duilleabhar,

díol do bhó agus ceannuigh arbhar.”

Similarly, it is known in English as:

“If the cuckoo sings on a bare thorn,

you can sell your cattle and buy corn.”

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Emyr Estyn Evans, Ireland’s first professor of geography, in his 1957 study of Irish folkways, remarked that it would be worthwhile to listen out for the call of the cuckoo on the first day of July, for to hear it was a sign of a good harvest.

Other predictions

Various accounts in the National Folklore Collection indicate that the cuckoo can be a harbinger of good or bad luck. Lucky the person who hears the cuckoo for the first time in his right ear but woe betide him if he hears it in his left ear.

When the cuckoo called, some would turn the coins in their pockets twice, believing it secured a year free from financial troubles. Yet, for those without a penny in their pocket, this superstition did not bode well.

In some regions of Ireland, it was believed that the direction faced upon hearing the cuckoo’s call could impact life expectancy, signalling a move in that direction before the year’s end – a bad omen for those facing towards a graveyard. Similarly, an entry in the Schools’ Collection from West Cork states,

“If a person hears the cuckoo for the first time after its visit, behind him, it is regarded as a sign that he, or some near relative of his, will die before the year is out.”

Writing in 1887, Lady Wilde (“Speranza”), an Irish poet and nationalist, noted that in one Irish family, a cuckoo always appears before a death.

There are ways to protect yourself against the bad luck that the cuckoo can bring. In 1896, the custom on first hearing the cuckoo was to say: “Go mairimíd beo ar an amsa seo arís. Amen.” (meaning “May we live to see this day again”).

A F F I L I A T E A D

This tradition continued into the 20th century as Galwegian Pádhraic Mac Giolla Phádhraic also advised in 1937 that when the cuckoo calls, respond with “Go mbeire muid beo ar an am seo aríst”. Just be sure to have your breakfast before you hear it or else a “mí-ádh” (“misfortune”) might befall you for the whole year.

Upon hearing the first cuckoo call of the year, young people in some parts of Ireland and Britain would inspect the soles of their shoes, and if they found a grey hair there, it was considered a sign that they would live long enough to comb their own grey hairs. This belief was held, for example, in Counties Clare and Offaly.

Please help support

Irish Heritage News

A small independent start-up in West Cork

Give as little as €2

Thank You

There was also a belief, recorded in Clare, that the “maiden who is the first to hear the cuckoo will be married before Hallowe’en”. If she discovered a hair on the sole of her left shoe upon hearing the cuckoo’s call, it was thought to predict the colour of her future husband’s hair. Hardy also recorded this tradition in the west of Scotland.

Recent cuckoo-inspired composition

A recent musical composition, “When the cuckoo sings in May”, written in the old traditional Múscraí style by Seán Ó Muimhneacháin, poignantly tells the true story of an ageing father anxiously awaiting the return of his ailing daughter:

“In efforts to restore her health, he sent her far away,

But she promised to return again when the cuckoo sang in May.”

But, alas, her health did not recover and yet the sound of the cuckoo at her graveside brought some measure of consolation:

“The friends who gathered ‘round her grave shed many bitter tears,

But lo! What sound or notes profound that now assail their ears?

The cuckoo’s song, so clear and strong, came wafting o’er the way,

And he knew she kept her promise, when the cuckoo sang in May.”

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Cuckoo’s current status in Ireland

Unfortunately, the National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) has reported a substantial decline in the cuckoo population across Ireland, with breeding numbers down by 27% between 1968 and 2011.

Last May, the cross-channel Cuckoo Tracking Project, conducted by the NPWS and the British Trust for Ornithology (BTO), satellite tagged three cuckoos in Killarney National Park in Co. Kerry and a cuckoo in the Burren National Park in Co. Clare. This collaborative effort aims to determine the factors contributing to the decline in the cuckoo population by closely monitoring migration patterns. By the autumn, the three Killarney cuckoos had made it to Central Africa, having flown thousands of miles.

Enthusiasts can follow these birds live and sponsor a cuckoo to support the ongoing research here. This project highlights the importance of collaborative efforts to preserve our wildlife.

Know any cuckoo-related folklore or sayings? Please share them with us in the comment section below!

Advertising Disclaimer: This article contains affiliate links. Irish Heritage News is an affiliate of FindMyPast. We may earn commissions from qualifying purchases – this does not affect the amount you pay for your purchase.

READ NOW

➤ Navan’s unusual horse grave and the pagan Viking horse cult

Birdwatchireland.ie

Dúchas, Main Manuscript Collection, vol. 0377, p.110; vol. 0481, p.250; vol. 0527, p.207. National Folklore Collection, UCD.

[https://www.duchas.ie

/en/cbe/volumes]

Dúchas, Schools’ Collection, vol. 0285, p.15; vol. 0596, pp.27-30; vol. 0812, pp.140-141. National Folklore Collection, UCD.

[https://www.duchas.ie

/en/cbes/volumes]

Evans, E. E. 1957. Irish folk ways. Routledge & Kegan Paul: London.

Hardy, J. 1879. ‘Popular history of the cuckoo’. The Folk-Lore Record 2, pp.47-91.

Mac Lir, M. 1896. ‘The folk-lore of the months. III, April’. Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Journal, ser. 2, vol. 2.16.

Ó Buachalla, C. 2023. ‘The Scairbhín: nature’s dramatic seasonal change in Ireland’. Gormú, 5 May 2023.

[https://www.gormu.com/

the-scairbhin-nature-s-dramatic-

seasonal-change-in-ireland]

Ó Crohan, T. 1986 (1st pub. 1928) Island Cross-talk: pages from a diary. Trans. by T. Enright. Oxford University Press.

Ó Muimhneacháin, S. 2019. ‘When the cuckoo sings in May’. [song] In The Cuckoo Sings in May. Lettertec, pp.2-3.

Swift, N. 2023. ‘The cuckoo in Irish folklore’. The Fading Year, 13 Apr. 2023.

[https://thefadingyear.

wordpress.com

/2023/04/13/

the-cuckoo-in-irish-folklore/]

Teanglan.ie

Wilde, J. 1887. Ancient Legends, Mystic Charms, and Superstitions of Ireland. Vol. 1. Ticknor & Co.: Boston.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T