From its inception in the early 19th century to its closure in 1956, Sligo Gaol housed a diverse inmate population. Among the many prisoners who endured its challenging conditions was Michael Collins. Efforts now focus on preserving this former gaol’s history and built heritage, while transforming it into a flagship visitor attraction.

In 1813, three commissioners appointed by the Sligo Grand Jury were tasked with overseeing the construction of a new county gaol on a 7-acre site on the eastern edge of Sligo town. About two-thirds of the prison was completed and ready for occupation five years later. This marked the beginning of a remarkable chapter in Sligo’s history.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Life in Sligo Gaol

Sligo Gaol was initially designed to hold 160 prisoners – many found themselves incarcerated here for minor offences and repeat offenders often made up a sizeable portion of the prison population. Men and women, as well as other categories of inmates such as debtors and those classified as “lunatics”, were segregated within the prison.

Sign up to our newsletter

The gaol was run by a modest workforce of between 10 and 22 individuals, which typically included the governor, deputy-governor, medical officer, matron, nurse, clerk, schoolmaster, watchman, several turnkeys, a local inspector and a barber who was tasked with stopping the spread of lice. There were also usually two or three chaplains – one from the Church of Ireland, one from the Roman Catholic Church and occasionally a Presbyterian representative. The local Ursuline Sisters were regular visitors.

Although conditions within the gaol were considered relatively good for the time, life within its walls was harsh. It soon earned a reputation for discipline and order. Inmates endured 12–14-hour work shifts daily with short breaks for food, exercise, instruction and prayer. They washed using buckets in the yards and ate their meals in their cells. The dietary regimen consisted primarily of oatmeal, Indian meal, potatoes, bread, milk and buttermilk. Regulations prohibited friends and relatives from delivering food to “pauper prisoners”.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

In the prison school, inmates learned to read and write and obtained some basic knowledge of arithmetic. Trades like shoemaking and tailoring were also taught. All prisoners were issued with prison clothing and footwear made within the gaol; their own clothes were removed on arrival at the prison, fumigated in an oven and placed in a store until their release.

Prisoners were responsible for all cleaning duties within the gaol. Other tasks included weaving, shoemaking, tailoring, making blankets, nets and mats, gardening, making bone manure, metalworking, coopering, carpentry and painting. Those sentenced to hard labour were usually engaged in stone-breaking, wood chopping and oakum picking – a fibre used in shipbuilding to seal gaps. From 1826, they also drove the treadmill, which was used to draw water from the Garvoge River to fill the tanks required for sanitation.

Female prisoners were expected to knit and sew as well as work in the laundry; some also undertook nursing duties. The matron was supported in her duty by some benevolent women in the town who were engaged in instructing the female prisoners.

The gaol’s capacity was severely strained during the peak of the Famine in the 1840s when a maximum of 291 inmates was recorded.

“The cells are large and airy, but so great is the crowd that beds have been laid down on the floors of all the day rooms, and every other available spot.”

In contrast, the installation of gas and a piped hot water heating system in 1879 earned the gaol the nickname “The Cranmore Hotel”, highlighting its comparatively luxurious accommodation. (The gaol is located near Cranmore Road.) For much of the 20th century, Sligo Gaol operated self-sufficiently, with inmates selling their produce in town on Saturdays and with the profits going towards the upkeep of the prison.

A F F I L I A T E A D

Prisoners

By the early 20th century, the number of inmates in Sligo Gaol had dropped significantly. Hangings continued within its walls until 1903. The last person executed was a Mr Doherty from Carrick-on-Shannon, Co. Leitrim, after he was found guilty of murdering his son.

>>> RELATED: Peaceful protest in turbulent times: the trial of Glenade Land League Secretary Brian McEnroy in Co. Leitrim, 1880–81

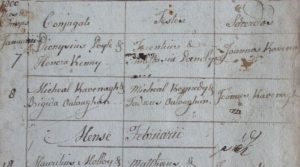

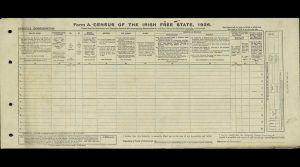

To gain insight into the prison population at this time, valuable information can be extracted from the 1901 and 1911 census returns, though the inmates are listed by their initials only. The prisoners mainly came from Connacht, Ulster and the Midlands. The majority were Roman Catholics, though some were members of the Church of Ireland. There was a mix of single and married prisoners and a small number of widowed inmates. The majority could read and write, but few had Irish. No illnesses were recorded among the prison population.

Please help support

Irish Heritage News

A small independent start-up in West Cork

Give as little as €2

Thank You

The 1901 census recorded 39 male and 13 female prisoners aged between 17 and 66, as well as a four-month-old boy – the baby of one of the female prisoners. They were imprisoned for all sorts of crimes: multiple types of assault (including assault of police), charges related to drunkenness and possession of illegal spirits, being in a licenced premises during prohibited hours, engaging in riotous behaviour, ill-treatment of children, vagrancy, false pretences, poaching, larceny, housebreaking, embezzlement, insubordination in the workhouse, stealing a heifer and some were held in contempt of court. All of these crimes were committed between 1899 and 1901 and their prison sentences ranged from 7 days to 12 months, while one individual, found in contempt of court, had an “unlimited” sentence. For their occupations, most of the men were listed as labourers, but there were also farmers, tinsmiths, a cattle dealer, a fisherman, a mason, a plasterer, a sweep, a hatter, a shoemaker, a baker, a shopkeeper and a clerk. The female prisoners were listed as housekeepers, dealers and prostitutes.

The 1911 census recorded 40 male and 5 female prisoners aged between 21 and 73, as well as a seven-month-old baby boy. Two of the inmates were in prison for manslaughter and were serving 12 months of hard labour. Other crimes listed included a range of assault and malicious injury charges, using threatening language, neglect and ill-treatment of children, uttering false coin (i.e. using counterfeit money), larceny, numerous robberies (of cattle, a watch, boots, socks, a shirt and drawers), breaking and entering, malicious damage, wandering abroad and begging, vagrancy, and several crimes related to drunkenness. All of the crimes were committed between 1909 and 1911, and their prison sentences ranged from 7 days to 18 months, though a few inmates were awaiting trial. Again, most of the men were listed as general labourers, but there were also farmers, an agricultural labourer, a cattle drover, a horse trainer, a tailor, a shoemaker, a carpenter, a cabinet maker, a tinsmith, a butcher, a shopkeeper and spirit grocer, and an itinerant musician and violinist. No occupation was listed for the female prisoners, but all were mothers.

Noteworthy among those incarcerated within the walls of Sligo Gaol were political activists, Fenians and IRA members. This included Charles Stewart Parnell, Michael Davitt, Michael Collins, Linda Kearns and Frank Carty, the Vice Commander of the Sligo Brigade and later Fianna Fáil TD, who orchestrated a daring escape from the prison in 1920; he also broke out of Derry Gaol the following year. Carty was not the only prisoner rescued from Sligo Gaol.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

During World War 2, several German spies were detained in Sligo Gaol. In September 1946, ten of the spies were released, eight of whom opted to stay in Ireland.

Michael Collins

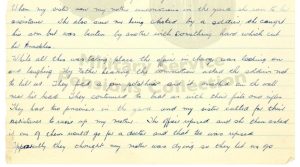

In April 1918, Michael Collins found himself a prisoner in Sligo Gaol after delivering a speech in Co. Longford purportedly advocating for arms raids. Despite being in solitary confinement for three weeks, he was permitted visitors and had access to newspapers. Collins kept a diary during this period, documenting his experiences:

“Thursday April 4th. Spent a hopelessly sleepless night. Don’t know why as I was tired enough going to bed. Mattress an awful thing. Reminded me of a sack half filled with sods of turf, except that the lumps of fibre didn’t seem to be as pliable as the sods of turf. Taken out on my own to exercise at 11.30.”

“Saturday April 6th. Have had still another sleepless night. Must try to get this wretched mattress changed. Katie called to see me this morning. Did not recognise me. It strikes me that I cannot have changed as much as all that. Poor thing somewhat upset… I wish to God I wasn’t in jail.”

Collins was eventually released on bail. Interestingly, according to Sligo Gaol Register, he gained a pound in weight while detained.

During a raid on one of Collins’ offices, he entrusted Sinéad Ní Dheirg, his personal secretary, with this diary. Collins told her to read it and decide whether to keep it or destroy it as she saw fit. The diary is now in the National Library of Ireland, has been digitized and can be read in full here.

>>> READ MORE: Maolra Seoighe: the hanging of an innocent Connacht man

The prison complex

The extensive prison complex cost somewhere in the region of between £22,000 and £30,000 to build. It was erected by John Lynn, based locally, to designs by Richard Ingleman. This ambitious building project was characterized by good-quality workmanship and utilized local Ballysadare limestone throughout.

Sligo Gaol stands as Ireland’s best surviving example of a prison complex featuring a distinctive polygonal cell block arrangement. Inspired by English philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s “Panopticon Theory”, this strategic design dictated the layout wherein a polygonal arc of cell blocks radiates outward from the governor’s house in the centre. This allowed the governor to closely monitor all activities within the prison and also move about easily. Both prisoners and guards were under constant surveillance.

Enclosed exercise yards filled the space between the governor’s house and the cell blocks, serving the purpose of promoting air circulation to prevent the spread of disease. There was a separate block on the site’s eastern side for housing female prisoners and there were designated areas for other types of inmates too. The guard house was located to the south of the cells and controlled access to the gaol.

The gaol underwent various expansions and improvements over the years to accommodate the growing inmate population. In the 1820s, a hospital was erected on the east side of the complex and on the west side, a marshalsea (debtors’ prison) and a treadmill. Later still, they added a schoolroom, dispensary, chapel and a high perimeter stone wall around the entire prison complex. These walls remain an imposing feature in Sligo town to this day.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Samuel Lewis described the prison complex in detail in his Topographical Dictionary of Ireland in 1837:

“The county gaol is a handsome and substantial building, erected on the polygonal plan … the governor’s house is in the centre, and the debtors’ ward and the hospital form two advanced wings; it is well adapted to the classification of the prisoners, each of whom has a separate sleeping cell; it has a treadmill for hard labour, a school, and a surgery and dispensary within its walls…”

The closure of Sligo Gaol

With ever-dwindling inmate numbers, the closure of Sligo Gaol came in 1956. Unfortunately, substantial portions of the compound were demolished between the 1960s and early 1980s; this included the female block, hospital, treadmill and much of the guard house. However, the iconic polygonal cell blocks, the governor’s house and the marshalsea (debtors’ prison) remain largely intact. Remarkably, they have retained their character and appear much as they did when the last prisoners departed for Mountjoy Gaol nearly 70 years ago.

The future for Sligo Gaol

Sligo County Council took ownership of the former prison complex in 1957, repurposing sections for administrative use and storage. In 2010, the local authority, aided by the Heritage Council, commissioned a conservation plan for Sligo Gaol, and small-scale conservation efforts have been underway since.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

A local voluntary group known as the “Friends of Sligo Gaol” has also been working tirelessly to preserve the gaol, promote awareness of its historical importance and make it accessible to the public. Together with the Sligo Local Community Development Committee (LCDC), they funded a feasibility study to explore the prospect of transforming the gaol into a tourism attraction. The report was carried out by CHL Consulting Ltd – the consultants behind the Titanic Centre in Belfast and Spike Island in Cork.

Their long-term vision for Sligo Gaol involves creating an immersive visitor experience, incorporating an interactive museum and event space. The feasibility report predicts 55,000 visitors annually but recommends a phased approach to the project.

In late May 2024, Sligo County Council secured €200,000 in funding to advance plans and designs for Sligo Gaol, and to carry out further public engagement and consultation. The council hopes to secure additional capital funding in 2025 for the renovation and adaptive reuse of this historic site.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

The funding, sourced from THRIVE, Town Centre First Heritage Revival Scheme, was awarded under the European Regional Development Fund’s (ERDF) Northern and Western Regional Programme 2021–27. This scheme provides local authorities with financial support to renovate and adapt derelict and vacant publicly owned heritage buildings in towns and cities.

Further details regarding Friends of Sligo Gaol’s future plans for the gaol and additional resources can be found on their website.

* Originally published in November 2023; updated in June 2024.

Advertising Disclaimer: This article contains affiliate links. Irish Heritage News is an affiliate of FindMyPast. We may earn commissions from qualifying purchases – this does not affect the amount you pay for your purchase.

READ NOW

➤ The workhouse cemetery: “Clonakilty, God help us”

➤ Golf’s early days in Sligo and its founding fathers

➤ Digitized records for Stanwix Widows’ Almshouses in Thurles now online

➤ The “Lady of the Lake”: Beezie and her island

➤ Excavation of Sligo’s Green Fort yields over 1,000 finds from 17th-century bastioned military fort

A D V E R T I S E M E N T