By Sheron Boyle

This week marked the 113th anniversary of the sinking of the RMS Titanic. In 1912, a beautiful 20-year-old woman was due to sail on the ship to begin a new life in America. Sheron Boyle tells how her Irish grandmother’s brush with the infamous Titanic tragedy was followed by a doomed love affair in the US and her inspiring tale of coping with adversity.

My image of my paternal grandmother, Margaret Boyle née Martin, was of an old lady with her dark, fine hair scraped back in a bun. A widow for many years, she dressed in the regulation black and white of her generation with the occasional navy blue thrown in as a nod to high days and holidays.

When we stayed at the family farm outside Milltown, Co. Galway, in the 1960s and 1970s, she wore workman-like black boots and I’d stare at them thinking how, back in my Yorkshire home city, I didn’t know any women who wore such footwear.

Life halted at 6pm in her bungalow as RTÉ (Irish TV) played the Angelus – the prayer of devotion traditionally recited in devout Catholic households three times a day. My grandmother stopped whatever she was doing, sat in her high-backed wooden kitchen chair and prayed. Then the television would be switched off – and covered with a tea towel while we ate our meal.

At night time, I’d quietly watch her silhouette as she knelt at her bedside to pray before she got into bed with me.

Her careworn face was lined and tanned – undoubtedly from years of running the farm, raising her seven children, caring for a disabled husband and tending the orphaned seven children on the neighbouring farm.

But though the top of her back was stooped as age took hold, her blue eyes always had a twinkle in them.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Today, her story would probably register as shocking. Back then, and in the harsh times of life in the first half of the 1900s, it was undoubtedly one replicated in all of Ireland’s counties.

Occasionally, it would be mentioned that my grandmother had been to America as a young woman. And more shockingly, she had been due to sail on the Titanic, joining the hundreds with a third-class ticket, hoping it would transport them to a better life across the Atlantic.

Sign up to our newsletter

It was a story I never, regrettably, asked her about. But it is said that on the anniversary of the ship’s sinking, 15 April, she would never talk about it and would feel ill.

>>> YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Talking to older people: questions to find out about Ireland’s past and your roots

I have spent years researching my family tree – long before the internet was in mass use – and as I garnered information, it made me reassess the old lady staring stoically into the camera in our family photos and see through fresh eyes the once beautiful young woman she was.

From at least the time of the Great Famine (1845–52), Irish people were forced to leave their homeland in order to survive. They really only had two choices: America or England. And so my ancestors emigrated to both lands. By 1890, two of every five Irish-born people were living abroad. By the end of that century, the population of Ireland had almost halved, and it never regained its pre-Famine level.

A F F I L I A T E A D

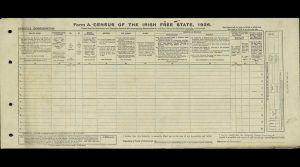

Over half of my ancestors went to the US. Born in 1891, Margaret was the seventh of 12 children of Thomas and Ellen Martin raised on a small farmstead in Rockfort in the townland of Levallyroe near Irishtown, Co. Mayo.

Missing the Titanic

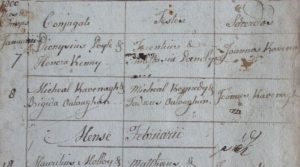

When the young 20-year-old decided to try for a new life in America, where at least three siblings had already emigrated, she paid £7 for her steerage-class ticket (no. 367167) and was booked to sail aboard the Titanic from Queenstown (now Cobh), Co. Cork, on 11 April 1912, along with around 120 other Irish passengers.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

She was due to sail with a cousin, Celia Sheridan. Family myth has it that thanks to Celia being late leaving her family home and so possibly unable to buy a ticket, the duo missed the boat – finally leaving 24 hours later on the SS Celtic. My grandmother cancelled her passage on the Titanic and her ticket (which incorrectly has her listed as Mary) simply states “Not boarded”.

>>> YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Irish connections with the doomed “Millionaires’ Ship”, the RMS Republic

Though she never discussed her brush with that fateful journey, she must have put herself in the place of those who perished on the ship that night? Her chances of survival were slim, with over 70% of steerage passengers dying.

However, when the “unsinkable” Titanic careered into an iceberg, Margaret was fast asleep in her cabin about 700 miles away.

Please help support

Irish Heritage News

A small independent start-up in West Cork

Give as little as €2

Thank You

Contemporary US newspaper reports indicate that news of the sinking – in which 1,517 passengers and crew died and just over 700 were saved – was kept from the Celtic passengers. As the New York Times, on Sunday, 21 April 1912, reported:

“The news that the Titanic had gone down was received by Capt. Hambelton of the Celtic last Monday, several hours after the liner went down, but it was not known among the passengers until last Wednesday, when it was posted on the bulletin board… The second- and third-class passengers did not learn of the disaster until Friday, when the liner was in halting distance of New York.”

The Chicago Tribune for 21 April reveals that the Titanic sent an SOS to the Celtic but other ships were nearer, adding:

“After Wednesday the nervousness spread. Few passengers, if any, took off their clothing when they retired. When Mrs H. C. Bergh, wife of a Rochester businessman, refused to go to bed, her example was followed by most of the married women passengers.”

And so, as Margaret was among the first passengers to sail into New York on 20 April, docking in the very bay where the Titanic should have been, it must have been a gloomy New World she entered.

But she must have thought how lucky she was to have missed the boat, in the very saddest sense.

A new start in America

Margaret went on to a new life – joining her sister and spinster aunt (both named Celia Martin) and working as a maid in Hartford, Connecticut, for the prosperous and politically-active Hooker family.

It was while in America that she posed for a handsome black-and-white photo with her sister Celia, her three brothers, Owen, Jim and Pat, and the latter’s wife Delia, all living in the Hartford area. Margaret is wearing a lovely white blouse, her lustrous brown hair piled high and her high cheekbones define her face.

Mr Blackburn, a love lost

Shades of her strong character emerged as it became known that she had become close to a man who, shockingly for the time, rumour had it was a non-Catholic and – probably as bad – was said to have German origins. My aunt Margaret Cleary – my father’s sister who lives in Manchester, Connecticut – believes his first name was possibly Michael and surname Blackburn.

I employed a genealogist to help me overcome the hurdles I faced when researching my grandmother’s story. Michael Rochford of Heir Line found a copy of her Titanic ticket and then, amazingly, helped track down a Blackburn family living in Connecticut in the early 20th century.

He discovered that the Blackburns left Dewsbury – a mill town in West Yorkshire, just 6 miles from my home today – where the father was a foreman and moved to Sagan in Germany (now Żagań in western Poland) to work in a mill there. A widower, he met and married a German woman and en masse they immigrated to Windsor Locks, Connecticut, which had a developing mill industry. Michael Blackburn was a product of his father’s first marriage, but had a German stepmother – hence the link.

A F F I L I A T E A D

Return to Ireland

The family story passed down is that at some point, my grandmother won a raffle and the unusual prize was a paid trip back to Ireland – so she went home – as yet I cannot find when.

I personally doubt there was ever a raffle and wonder if it was a story put out by her family. Did her spinster aunt, then in her 50s, disapprove of the relationship? Did she write to her brother and his wife, telling them what their beloved daughter was doing, which led them to order her home?

With the religious and cultural differences, Margaret and Michael were never going to be, though as she left America for good, he gave her a gold ring with the letter “M” engraved inside it. In the romantic sense, they were ships that pass in the night. She later told a neighbour it was an engagement ring.

New beginnings in Galway

Margaret’s effort to carve out a new life in the bright New World ended not as she hoped. And so in 1923, at the relatively late age of 32, she wed my grandfather, Michael Boyle, a man several years older than herself. It was thought to be a semi-arranged match.

They settled at his family homestead in a hamlet called Emeracly (Ummeracly) outside Milltown, Co. Galway. After fathering seven children, including a set of twins, Michael succumbed to arthritis – so severe that my own father could never recall seeing him walk.

Sign up to our newsletter

But the redoubtable Margaret coped with her lot, running the small farm, raising her brood and overseeing the seven neighbouring orphaned Donnelly children. When the authorities came to take them to children’s homes, she put her cattle on their land and simply refused to allow them to be split up. To this day, the Donnellys – many now in Philadelphia – credit her with keeping them together.

My grandmother’s legacy

The circle of life continued and – as countless other families had to – Margaret waved off one son, Pat and three daughters, Mary, Margaret and Philomena, to the US, and my father, Michael and his brother, Jimmy, for the UK, while the youngest, Sean, stayed behind to run the family farm.

In their late teens, my dad, with his lifelong pal, Jimmy Donnelly, travelled to Lincolnshire and the North Yorkshire market towns, where they slept above the pigs in a barn and hired themselves out for work.

Dad eventually settled in Wakefield and worked for decades as a miner and a labourer. His siblings settled to varying degrees in the US. My aunt Margaret was just 16 when, in 1948, she left their thatched cottage home – with no electricity or indoor toilet – and flew to New York for a new life.

My generation of the family undoubtedly benefited from their hard work – we were the first to go to university, travel the world for pleasure not necessity and have genuinely comfortable lives.

After Granny died from old age – at the great age of 92 in 1982 – her wedding ring and her lost love’s ring – which she had kept all her life – were passed to her daughter Mary in Philadelphia.

Chance encounter with Mr Blackburn

As for Granny’s lost love, my aunt Margaret Cleary was introduced to Mr Blackburn at a social event in Hartford in the 1950s, where she had settled.

Mother-of-five Margaret Cleary, now 95 and living in Manchester, Connecticut, recalls the meeting:

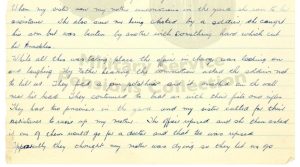

“It was at a picnic and my Uncle Pat Martin, a bus driver, introduced us. Mr Blackburn was told I was Margaret’s daughter but he said he knew straight away who I was as I looked like my mother.

I think his first name was Michael. My mother told me about him when I was young. I wish now I had asked her more but you don’t think about it at the time.”

Mr Blackburn told my aunt that he had never married but was very pleased to meet her. Did he always hold a candle for my grandmother?

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

My grandmother told a friend she regretted leaving America. I took my children to see the house where she worked as a maid and thought, why wouldn’t she feel sad – leaving her first love, a new life filled with hope in the New World, to return to the hard life of rural Ireland. She put duty and family before love and life in America.

One day, I hope to tell her story in a book. Meanwhile, it is left to us, the descendants she left behind, to ponder how different life would have been if Margaret Martin had boarded the Titanic – if she had not missed the boat in many senses of her life – but such was the journey she took that brought me to be born and raised in Yorkshire.

If anyone has any information about the Martin or Blackburn families, email Sheron at sheronboyle@aol.com, or you can find her on Facebook here or X here.

Sheron Boyle is a freelance journalist and writer with 35 years of experience reporting for the UK and Irish national press, specializing in crime and human interest stories.

Advertising Disclaimer: This article contains affiliate links. Irish Heritage News is an affiliate of FindMyPast. We may earn commissions from qualifying purchases – this does not affect the amount you pay for your purchase.

READ NOW

➤ Oasis brothers Liam and Noel Gallagher’s Irish heritage traced through Meath and Mayo

➤ From Mayo to Buckingham Palace: the legacy of Tom Mulloy, an untrained “genius”

➤ RIC barracks under siege in Clarinbridge and Oranmore, Co. Galway, during the Easter Rising

2 Responses

What a lovely inspiring story and Margaret sounds like a wonderful, strong and caring woman. I would just like to comment on the sentence “…they really only had two choices: America or England….” In fact, many thousands of Irish people also emigrated to Australia (and indeed to Canada) before, during and after the great famine – 95% of my ancestors included (one ancestor emigrated from Cornwall) – and established excellent lives for themselves and their Australian descendants.

I know that my great grand father and mother came from Ireland around 1868. There last name was O”Connor my name is Laughlin and used to be Mc Laughlin. I did the DNA Ancestry, which said I was 79% Irish and the rest Misc. Since my mother side came from England I called and questioned ancestry. They pulled my DNA file and said my DNA was tested 40 times and each time it was 79%. I have been to Ireland once and thought about going back. Such a beautiful country especially the cliffs of

Moher. I have read a lot of books about Irelands history and enjoyed reading Micheal Collins life. Also the five books by Morgan Llywelyn of 1916 to 1979. I love your story and the pictures. Thank you