By Dr Michael Flavin

Dr Michael Flavin reflects on the experiences of the Irish following the IRA bombings on British soil in the 1970s, detailing the discrimination and abuse they faced in Britain, while recounting his own family’s fears during this time.

The Troubles in Northern Ireland lasted 30 years and cost over 3,500 lives. The conflict took place in the six counties of the northeast, with an identifiable epicentre in Belfast, but that is only part of the story because The Troubles spilled far further than that.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

On 17 May 1974, bombs in Dublin and Monaghan killed 35, including an unborn child and injured almost 300. The attack was carried out by a Loyalist paramilitary group – the Ulster Volunteer Force.

The conflict travelled further south. Paramilitary groups needed money for arms, and on 7 June 1978, the Irish National Liberation Army (a breakaway faction from the Official IRA) staged a raid on a security van in Barnagh Gap, Co. Limerick. One of those involved later died in the hunger strike of 1981.

The Troubles travelled still further. A Provisional IRA bombing campaign in Britain in the early 1970s brought more publicity to the conflict, as had been intended. The most notorious incidents included the Guildford Pub Bombings of 5 October 1974, in which four soldiers and one civilian were killed and more than 60 injured.

The violence worsened on 21 November 1974 when two pubs in Birmingham were bombed, killing 21 and injuring over 180. The British parliament responded by passing the Prevention of Terrorism Act, which allowed police to detain terrorist suspects for seven days without charge.

Sign up to our newsletter

Before this bombing campaign, it was relatively easy to be Irish in Britain. Lazy anti-Irish racism – in the form of the ubiquitous Irish jokes of the period – was a constant, minor irritant, but Irish people were generally left to their own devices, interacting quite harmoniously with the home population. Most Irish families in Britain went to Mass every Sunday, had holy water fonts in their homes, where the Sacred Heart took pride of place and the children attended Catholic schools.

Following Ireland’s War of Independence and Civil War, which somewhat stunted socioeconomic development, as well as the food and fuel shortages experienced in Ireland during World War 2, the extended period of post-war reconstruction in Britain represented opportunity for the Irish. In the absence of immigration controls, there was an influx of Irish people seeking jobs in Britain in construction, in factories, in the transport industry and in the new National Health Service. Free education was available up to the age of 18, with the added prospect of free or grant-supported university places.

A F F I L I A T E A D

Not that moving to Britain for work was a revolutionary development after WW2. Large-scale emigration had been a reality since the Great Famine (1845–52). Irish labourers (navvies) were fundamental in constructing Britain’s railway network, yet Charles Dickens failed to have even one Irish character in his extensively populated novel, Dombey and Son (1846–48), in which the construction of the railways is a substantial element. Often working in life-threatening conditions, the Irish were simultaneously essential and invisible.

After WW2, Irish immigrants once again proved vital, rebuilding Britain’s infrastructure and maintaining its services. At the same time, the Irish retained their own distinct identity.

In Birmingham, in 1967, the Irish Development Association founded the Irish Centre – a community hub. I first visited the Irish Centre, located on Digbeth High Street, as a small child in the 1970s, prior to the pub bombings. The stage had a painted backdrop of an archetypal Irish landscape: a chequered patchwork of fields, a river, a lone cottage with a plume of peat smoke. Meanwhile, at the bar, pints of Guinness lined up in various stages of composition.

It was a place for families and for single men cutting loose after a week’s work. It was a space, too, for young people, both first- and second-generation Irish, to find partners. Many met their future spouse on the dance floor, perhaps flung together in the loosely organized chaos of the “Siege of Ennis”.

Music at the Irish Centre was constant. Some of it came from the traditional repertoire, but more came from the country and Irish scene, in which the established musical patterns, phrases and instrumentation of country and western were augmented by culturally and geographically specific references: “Pretty Little Girl from Omagh”; “The Galway Shawl”; “Along the Wicklow Hills”. Big stars of the Irish dance hall circuit, including Dickie Rock and Brendan Shine, drew Irish crowds to British venues.

Starting in 1952, there was a St Patrick’s Day parade in Birmingham each year, which provided the Birmingham Irish with an opportunity to celebrate their identity. Individual county ties subdivided national identity into the local and regional. It wasn’t just the nation you came from that mattered. It was also your county; your nearest town; your parish; your townland. There was more than one form of Irishness in Britain, an economically, socially and culturally active community resisting homogenization, despite the reductive and often dangerous Irish stereotypes appearing everywhere in the media.

The IRA’s British bombing campaign and, in particular, the Birmingham Pub Bombings changed all that. The Irish Centre was attacked, as were Catholic schools and churches. Having an Irish accent could result in a refusal of service in shops. Cheques drawn against Irish banks were declined. Traders in Birmingham’s Bull Ring market refused to handle Irish goods. Irish factory workers were sent home, at risk of assault from their colleagues. In Longbridge, 1,500 workers marched in protest against the bombings, carrying banners calling for those responsible to be hanged.

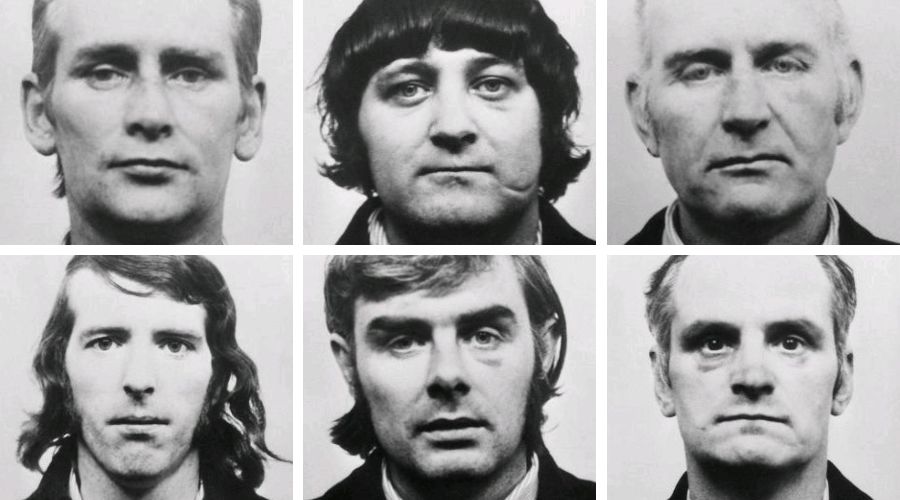

The police were under tremendous pressure to catch the men who had bombed the Birmingham pubs and, within hours, they detained five men at Heysham port. Four were from Belfast; one from Derry. They were travelling home to visit family and to attend the funeral of Birmingham IRA volunteer James McDade, who died on 14 November while planting a bomb at the telephone exchange in Coventry.

The five men were taken to Morecambe police station for a forensic test, overseen by Dr Frank Skuse. He concluded two of the men had recently handled explosives. Excellent police work had caught the bombers – hadn’t it?

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

No. The forensic test should have been repeated for confirmation. It was not. A brutal onslaught of violence ensued, as a result of which three of the five men confessed. A sixth man, arrested in Birmingham, was also maltreated and also confessed.

The written confessions contradicted each other and further contradicted known facts about the explosions, established once the crime scenes had been examined. No matter. The Birmingham Six were sentenced to life in prison on the basis of what the judge called, “The clearest and most overwhelming evidence I have ever heard”. He was later elevated to the House of Lords.

As for the Birmingham Six, they remained in prison until 1991 when they were acknowledged as victims of an infamous miscarriage of justice. The four convicted of the Guildford Pub Bombings were also innocent. Wrongful convictions of Irish people in British courts were a feature of The Troubles. As for Dr Skuse, whose evidence was central to the conviction of the six, he was retired, aged 51, on the grounds of “limited effectiveness”.

A F F I L I A T E A D

Life became hard for the Birmingham Irish, and for the Irish in Britain as a whole, living in a climate of suspicion. Birmingham’s St Patrick’s Day parade ended, not to be brought back until 1996. Its Irish Centre continued to operate and GAA games were played at Glebe Farm, east of the city, but the community did not often raise its head above the parapets. It lived within itself and stoically kept on working, benefiting the British economy and society.

A perception of Irish people as sub-human savages, which goes back to the original colonization of Ireland in the mid-12th century (and earlier), persisted into the 1980s. The IRA’s Brighton Bomb of October 1984 came close to killing the then Prime Minster, Margaret Thatcher. In its aftermath, Sunday Express editor Sir John Junor asked, in his newspaper column, “wouldn’t you rather admit to being a pig than to being Irish?”

Sign up to our newsletter

These racist perceptions were challenged by Republican prisoners campaigning for political status in Northern Ireland’s prison system. The labelling of Republicans as mafiosi figures without authentic support was undermined by the election of hunger striker Bobby Sands as Member of the British Parliament for Fermanagh and South Tyrone. Those of us growing up Irish in the UK at the time were transfixed by the determination shown by the prisoners, alerting us to the political and legal aspects of a conflict that had previously been played out through bombs and bullets alone in the British media.

The Irish in Britain did not accept their demonization. They continued to work, to socialize and to express their culture through music, sport and literature. My own novel, One Small Step, describes what it was like to be Irish in Birmingham in the immediate aftermath of the bombings, when adults feared the next knock at the door. My own parents quietly disposed of a vinyl album of Irish rebel songs. It was not safe to be Irish in Birmingham. Innocent people had already been lifted by the police: you could be next.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

The concentric circles sent out from The Troubles spread wider. The Irish diaspora in the USA could sometimes be a source of support for Irish Republicans, but it was also a vital friend during the peace process of the 1990s, when the Armalite gave way to the ballot box. The presence of President Clinton in the peace process showed the high profile and high stakes of the negotiations, helping to bring all parties to the table.

Much has changed since the Troubles ended with the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 and an entire generation has grown up post-conflict. Ireland is a dynamic and confident European nation, and Irishness is no longer stigmatized but celebrated.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

The recent 50th anniversary of the Birmingham Pub Bombings was marked respectfully, though pressure continues to be exerted by relatives and friends of those lost to bring the two surviving alleged bombers to justice. One of the many appalling outcomes of the bombings is the fact that the real bombers remain free while innocent men were beaten, framed and convicted.

An exhibition of “The Irish in Britain at 50”, funded by the UK’s National Lottery, toured internationally in 2023–24 (I was one of the interviewees for the oral history project, which remains an important archive).

The children of the emigrants who came to Britain in the 1950s and 1960s have found partners within and beyond the Irish community; their descendants carry their DNA and hold an appreciation of Ireland’s culture and history, and an optimism about its future.

Dr Michael Flavin is an academic at King’s College London. His Troubles novel, One Small Step, is available via Amazon.co.uk and Amazon.com.

Advertising Disclaimer: This article contains affiliate links. Irish Heritage News is an affiliate of FindMyPast. We may earn commissions from qualifying purchases – this does not affect the amount you pay for your purchase.

READ NOW

➤ Oasis brothers Liam and Noel Gallagher’s Irish heritage traced through Meath and Mayo

➤ A guide to navigating Northern Ireland’s church records

➤ Clogagh: a small West Cork community transformed by the Revolution

➤ Did your ancestor spend time in a workhouse?

➤ Tracing John F. Kennedy’s Irish ancestry through Wexford, Limerick, Cork and Fermanagh

A D V E R T I S E M E N T