We explore the possibility that Yeats’ most famous poem was inspired not by Innisfree but by Church Island on Lough Gill, Co. Sligo. Here, we investigate the geography of the region and look at other romantic literary references to this place.

There are about 20 islands and islets on Lough Gill, which sits on the boundary between Counties Sligo and Leitrim. This includes the tiny island of Innisfree of Yeats fame. Although William Butler Yeats was born in Dublin in 1865, his parents had strong Sligo connections and he spent considerable time there during his childhood when the poet-to-be was powerfully affected by the western landscape.

“I had still the ambition, formed in Sligo in my teens, of living in imitation of Thoreau on Innisfree, a little island in Lough Gill, and when walking through Fleet Street very homesick I heard a little tinkle of water and saw a fountain in a shop-window which balanced a little ball upon its jet, and began to remember lake water. From the sudden remembrance came my poem ‘Innisfree’, my first lyric with anything in its rhythm of my own music.” (W.B. Yeats, 1916)

Some have since questioned the above statement.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Innisfree

Yeats died in France in 1939 and was buried there but his remains were later disinterred and laid to rest in Drumcliff churchyard, Co. Sligo, in 1948. Inspired by this momentous occasion, Sligoman Joe Jennings – then a budding journalist and later government press secretary – visited Innisfree. In the 1950s, writing for the Sligo Champion, he controversially declared that Innisfree could not have served as the muse for the acclaimed poem. Being less than an acre in area, he argued that the island is too small to have accommodated habitation and does not align with the poem’s description:

“[It] is covered in rough shrubbery, It is probably the most inhospitable place in Lough Gill! With difficulty we tried to have a look around Innisfree, Our verdict was instantaneous. This could not be the place Yeats had in mind when he composed the famous poem!” (Joe Jennings)

In Yeats’ own words, it was the American poet Henry David Thoreau (1817–62) whom he sought to emulate. But Thoreau’s cabin was built on a 14-acre plot of woodland and pasture on the shores of Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts, a much more congenial site than Innisfree.

Church Island

Jennings proposed instead that Yeats’ poem was inspired by Church Island (Inis Mór), the largest island on Lough Gill at over 40 acres. Sited on it are a medieval church, a cemetery and a monument known as Our Lady’s Bed, which is traditionally believed to have provided protection for pregnant women.

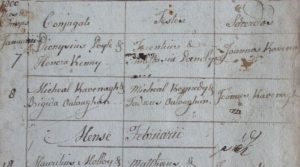

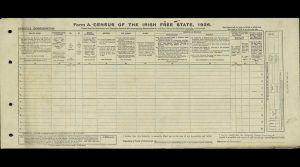

There was also plenty of room for a cabin, bean-rows, beehives, numerous glades and anything else the poet-heart desired. Certainly, it was still sustaining human life in the first half of the 20th century as several records indicate. No such evidence exists for life on the inhospitable Innisfree and some 20th-century sources claim that local fishermen had taken to calling it “Rat Island”! However, Joseph Cahany – who has a great knowledge of local placenames – maintains that the fishermen were probably referring to a different island called “Ráth Island” (also known as “Wolf Island”) on the western shore of the lake.

Sign up to our newsletter

Some locals shared Jennings’ belief and shortly after he had advanced his theory, it was confirmed by an elderly local man named Pat Carroll, who had connections with nearby Clogherrevagh House and recalled the poet visiting the house and his frequent trips to Church Island. The Wynnes resided at Clogherrevagh House and their extensive estate – owned by the Ormsby-Gore family – included Church Island as well as many of the islands on the lake and much of the land around Lough Gill. Innisfree was not part of this estate.

The logistics of travelling to the islands should be taken into account. Clogherrevagh House (now St Angela’s College) is on the northern shore of Lough Gill. Innisfree, positioned on the lake’s southeastern end, is more than a 2km boat trip from the house. On the other hand, Church Island is just 0.4km from Clogherrevagh, as well as being visible from the estate’s boathouse on the shoreline.

>>> RELATED: Church Island on Lough Gill: its history and archaeology

But perhaps Yeats approached Innisfree from the southern lakeshore? Reminiscing about his childhood, he stated: “I planned to live some day in a cottage on a little island called Innisfree, and Innisfree was opposite Slish Wood”. Slish Wood is an extensive oak forest on the southern shore of Lough Gill, not far from Innisfree and was part of the Wynne estate. Although certainly a greater distance from the woods, Church Island could also be described as being opposite the woods, and so Yeats’ description is of little help.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

It was suggested by Jennings that using poetic license Yeats had sidelined Church Island, opting instead for the more romantic-sounding name of another of Lough Gill’s islands. Of course, this all remains conjecture. But this was not the first time Yeats had reinvented a placename. In “The stolen child”, written in 1886, Slish Wood was referenced under the more beguiling name “Sleuth Wood”.

Cottage Island

The identification of Yeats’ inspiration may never be satisfactorily resolved but another possibility less frequently mooted is the 15-acre Cottage Island on the western end of Lough Gill, also visible from Slish Wood.

>>> RELATED: Cottage Island on Lough Gill: its history and archaeology

It was home to Mrs Bridget “Beezie” Clerkin, the last human inhabitant of Lough Gill. Tragically she fell into the open-hearth fire in her home on the island in 1949 and died aged 78. It is still known today by locals as Beezie’s Island.

>>> RELATED: The “Lady of the Lake”: Beezie and her island

Lough Gill’s Literary Yield

While it has been argued that “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” should be understood as representing a state of being rather than a specific geo-reference, after its publication there was an outpouring of creative works espousing the natural beauty of the region. For example, local amateur poets Terry O’Toole from Manorhamilton and T. Slevin from Clogherrevagh both composed poems titled “Lough Gill”, which were printed in the Sligo Champion in 1896 and 1929 respectively; both refer to Church Island, while Slevin’s poem also mentions Innisfree.

But Yeats was not the first to recognize the charm of Lough Gill. In 1837 Samuel Lewis in his Topographical Dictionary of Ireland stated that,

“The scenery is very romantic and is greatly embellished with the highly cultivated demesne of Hazlewood, the handsome residence of Owen Wynne, Esq. The lough is studded with islands, of which Church and Cottage islands are the largest. At Hollywell is another demesne belonging to Mr. Wynne, from which mountains covered with wood, the lake with its numerous islands, and the road sometimes running under stupendous rocks and sometimes through small planted glens, present scenes of great beauty.”

In 1883, just five years before Yeats penned his famous poem, fellow nationalist Patrick Grehan Smyth from Ballina, Co. Mayo, published a semi-fictional novel titled The Wild Rose of Lough Gill (an earlier version had been printed in Dublin Weekly News). Set during the period of the 1641 Rebellion and its aftermath, it tells the love story of Edmund O’Tracy and his wild rose, Kathleen Ní Cuirnin. In reality, the O’Cuirnins were an important family in this region and were intrinsically linked with Church Island. In the late medieval period, they resided on the island and were the chroniclers in poetry and music for the Ó Ruaircs in whose territory Lough Gill lay. They were also the hereditary keepers (caretakers) of the ecclesiastical treasures of this church.

Yeats and Smyth both mingled reality with fiction, recognising that Lough Gill offered escapism. “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” expresses the urban-dwelling poet’s longing for the peace and tranquillity of island life, while Smyth too romanticized the solitude of life on Church Island, which was much at odds with the eventful life of the main protagonist:

“Very soon a break in the wood showed him [Edmund O’Tracy] the peaceful bosom of the beautiful lake, sleeping under the silvery green veil of the moonlight, which gilded the surrounding woods, as well as the old ivied ruins on Innismore, or Church-island, where of old it is said St. Loman, the nephew of Patrick, watched, and prayed, and fasted. It was a sweet and peaceful scene, suggestive of calm and holy meditation, and quite at variance with the stormy thoughts and anxieties that throbbed in the spectator’s breast, as, reining up his horse for a few moments, he gazed with a kind of involuntary admiration on the lovely prospect.”

Elsewhere Smyth provides further description of the lake’s scenery and like Yeats’ poetry, he expresses the effect of this natural landscape on the senses:

Elsewhere Smyth provides further description of the lake’s scenery and like Yeats’ poetry, he expresses the effect of this natural landscape on the senses:

“The sunlight gilt … the venerable ruins on Church Island; and here and there from amidst the trees a thin blue wreath of smoke ascended into the still air from the thatched hut of a brughaidh or farmer — almost the only tokens of human life visible in the landscape.

The vesper voice of Nature sounded sweet and low. Now and then a stray zephyr rustled the branches of the trees, seeming to shake off flakes of sunlight into the shadowy recesses of the wood. There was an occasional drowsy lowing from the kine in the pastures, a cooing of amatory doves in the depths of the wood, the rustle of a rabbit among the tall grass and fern, the shriek of a skimming seagull, or the plash of a water-fowl. These and other sounds mingled at intervals with the gentle, dreamy ripple of the wavelets on the shingle; but the hush of eve was growing deeper every moment, and the sounds that broke its silence seemed to add to its tranquillity.”

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Regarding this publication, suffragette Hanna Sheehy-Skeffington (1877–1946) commented in 1935:

“I recall my first acquaintance many years ago, through fiction, with the beauties of Lough Gill in a now old-fashioned novel, still readable “The Wild Rose of Lough Gill.” Sligo still reads it, for I noted it in local bookshops and libraries side by side with books on Countess Markieviez and Yeats’ poetry.”

Like “Innisfree”, Smyth’s historical novel found a special place in popular imagination and “The Wild Rose” was adopted as the name of an annual festival in nearby Manorhamilton, Co. Leitrim. First held in 1970, the festival was inspired by the exploits of the original Wild Rose, Kathleen of Lough Gill, and was traditionally a weeklong celebration of homecomings and family reunions for thousands of emigrants from this region of Ireland.

READ NOW

➤ Your essential visitor’s guide to Lough Gill

➤ Church Island on Lough Gill: its history and archaeology

➤ Cottage Island on Lough Gill: its history and archaeology

➤ The “Lady of the Lake”: Beezie and her island

➤ How Our Lady’s Bed on Church Island protected expectant mothers

Beckett Crowe, N. 2015. ‘Patrick Grehan Smyth’. Our Irish Heritage.

[https://www.ouririshheritage.org/

content/archive/

people/101_mayo_people/arts-craft-and-culture/patrick_grehan_smyth]

Birth record, Bridget Byron, 23 May 1871, Cottage Island, Sligo.

[https://civilrecords.irishgenealogy.ie/

churchrecords/images/birth_

returns/births

_1871/03285/2204116.pdf]

Brown, T. 2016. ‘Yeats, William Butler’. Dictionary of Irish Biography.

[https://www.dib.ie/biography/yeats-william-butler-a9160]

Census of Ireland, 1911, ‘house 1 in Church Island (Lough Gill) (Calry, Sligo)’.

[http://www.census.nationalarchives.

ie/pages/

1911/Sligo/Calry/Church_Island

__Lough_Gill

_/756025/]

Census of Ireland, 1911, ‘house 1 in Clogherrevagh (Calry, Sligo)’.

[http://www.census.nationalarchives.

ie/pages/

1911/Sligo/Calry/Clogherrevagh

/755863/]

Death record, Bridget Clerkin, 8 Dec. 1949, Cottage Island, Lough Gill, Sligo.

[https://civilrecords.irishgenealogy.ie/

churchrecords/images/

deaths_returns/

deaths_1949/04536/4195767.pdf]

FitzPatrick E. 2012. ‘Formaoil na Fiann: hunting preserves and assembly places in Gaelic Ireland’. Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium 32, pp.95-118.

Griffith’s Valuation, 1848–64, Parishes of Calry and Killerry.

[http://www.askaboutireland.ie/

griffith-valuation/]

Hopper, K. 2008. ‘A sense of place: W. B. Yeats and ‘The Lake Isle of Innisfree’’. Geography 93(3), pp.176-80.

Jennings, J. ‘Church Island – Yeats’ beloved Lake Isle of Innisfree?’ Sligo Champion, 5 Nov. 2007.

Lewis, S. 1837. A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland. Lewis and Co.: London.

Schools’ Folklore Collection, vol. 0161, p.310.

[https://www.duchas.ie/

en/cbes/4701688/4692715]

Sheehy-Skeffington, H. ‘The Killarney of the West’. Irish Press, 14 Oct. 1935.

Sligo Champion, 18 Jul. 1896; 27 Jul. 1929; 20 Feb. and 7 Aug. 1954.

Smyth, P. G. 1883. The Wild Rose of Lough Gill. Gill and Son: Dublin.

Yeats, W.B. 1893. The Countess Kathleen: And various legends and lyrics. Roberts Bros: Boston.

Yeats, W.B. 1999. W. B. Yeats Autobiographies. W.H. O’Donnell and D.N. Archibald (eds) Macmillan: New York.