This feature explores the history and folklore surrounding Our Lady’s Bed on Church Island, Co. Sligo.

Church Island (Inis Mór) is the largest island on Lough Gill which sits on the modern-day boundary of Counties Sligo and Leitrim. There you will find a medieval church and cemetery, and a most unusual monument with an intriguing story.

Our Lady’s Bed

“Our Lady’s Bed” has been described variously as a cavity in a rock, a cromleac, a saint’s bed and most recently it was classified by the National Monuments Service as a “Ritual site – holy/saint’s stone”, a categorization applied to monuments “associated with a particular saint, and may be considered to have certain miraculous properties”.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

This obscure monument attracted much attention from antiquarians as early as the 18th century, starting with Englishman Francis Grose in 1791 who visited the island as part of an archaeological expedition to Ireland during which he suffered a fatal stroke in Dublin.

In 1904 William J. Fennel provided the most detailed report to date of Our Lady’s Bed, explaining that it was

“a rude construction more like a poor attempt to build a cromleac than an oratory or a devotional cell.”

Unfortunately, none of the antiquarians included a photograph of the monument in their accounts.

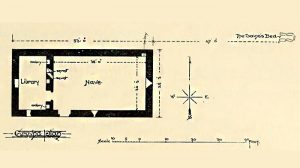

Although it is often described as being adjacent to the church doorway, which is in the south wall, Fennel’s drawing (pictured above) clearly shows it located about 15m east of the northeastern corner of the church.

This confusion regarding its location is difficult to reconcile, though local man Joseph Caheny suggested to us that this can possibly be accounted for by the existence of two different monuments: 1. the Saint’s Bed (a tomb-like structure) a short distance to the east of the church and 2. Our Lady’s Bed (a cavity in a rock) beside the doorway of the church. Fennel, on the other hand, clearly believed that the Saint’s Bed and Our Lady’s Bed were one and the same, stating:

“A certain amount of fame seemed at one time to hover round the ‘Saint’s Bed’, or as it is sometimes called ‘Our Lady’s Bed’.”

Sign up to our newsletter

For the purpose of this article, we will follow Fennel and assume that his interpretation is correct. By the time he had visited the island at the start of the 20th century, the monument was in a ruinous state.

Rituals performed on Church Island

Our Lady’s Bed was believed to have protective and curative powers, specifically for pregnant women. Grose explained that pregnant women would enter the monument and

“turn thrice around, which they believe prevents their dying in labour; at the same time they repeat certain prayers.”

Almost identical descriptions of this curious custom were provided by James McParlan in 1802, Thomas Dudley Fosbroke in 1817, Samuel Lewis in 1837 and again in 1882 by Sligo antiquarian William Gregory Wood-Martin. The latter two added that it was performed lying down and Lewis provided the alternative name “My Lady’s Bed”.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Fennel offered a more detailed account of the ritual:

“… it [Our Lady’s Bed] is said to have possessed a sacred power, which made it a place of frequent resort for women who desired the blessings of maternity. The ritual required the aspirant to enter it feet foremost, which was accomplished by wriggling in and turning over three times and always to the right, repeating each time ‘In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost,’ and then emerging, and having said three ‘Our Fathers’ and three ‘Hail Marys,’ the rite was complete.”

Sign up to our newsletter

Although in 1882 Wood-Martin stated that the ritual associated with the then overgrown monument had long ceased, Fennel spoke to an inhabitant of the island in 1904 who claimed that she knew an American woman who,

“desiring such blessings, came, in good faith, to ‘Our Lady’s Bed,’ and observed its ancient rite, with the result that the ‘blessings’ came afterwards to her abundantly, and in quick succession.”

In 1885 Irish author Ethel Greene (d.1887) wrote a fictional tale called “St Patrick’s Ford” in which the saint visited Church Island and there married fugitives Eva An Geanamuil and Cormac Ulla; she added: “Patterns used to be held on the Island, and up to the present day, it is much resorted to by lovers, who believe that a visit to this shrine will ensure them a blissful ending to their wooing”. Of course, this is a fictional piece but the linking of this place with a fruitful union possibly stemmed from the lore that had built up around Our Lady’s Bed over the centuries. Greene’s story also ties in nicely with the existing legend of Innisfree, a tiny island on Lough Gill 1.8km southeast of Church Island, where two mythological lovers are said to be buried.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Where can we find similar monuments?

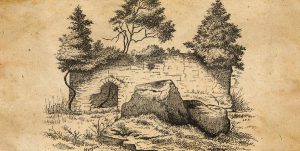

There is also a medieval church site on a nearby island on Lough Gill, called Cottage Island. Interestingly a curious monument in a ruinous state has been recorded near the church on Cottage Island (pictured below). It is not unlike Our Lady’s Bed and has also been compared to a “cromleac” and a “cist”, though it may have formed part of an enclosure surrounding the church.

Some antiquarians could have mixed up the two monuments, as well as confusing Church and Cottage Islands. This confusion is a real possibility because these two islands are the largest on Lough Gill and were the only ones occupied in recent times, both being the homes exclusively of families named Gallagher in the 19th and 20th centuries.

>>> READ MORE: Cottage Island on Lough Gill: its history and archaeology

Fennel’s statement comparing Our Lady’s Bed to a “cromleac” is intriguing. This outdated term typically refers to a prehistoric megalithic monument and in Ireland, it was most commonly applied to portal and wedge tombs. But given the ecclesiastical context and seemingly small size of Our Lady’s Bed, it is far more likely that it resembles some sort of shrine.

For example, gable shrines found on early medieval church sites are formed by slabs that incline towards one another to form an inverted V‐shape (pictured below), in a somewhat similar fashion to the much larger stones forming prehistoric tombs. These shrines were constructed over what was believed to be the grave of the founding saint and some housed translated relics.

Fennel’s plan of Our Lady’s Bed also deserves attention (see above). The drawing shows that it was entered from the west end and was formed by two rows of two edge-set stones, with a stone positioned perpendicular to these at the east end or rear of the monument. An interesting parallel comes from the early church site of Iniscealtra on Lough Derg, Co. Clare, where the internal structure of the Confessional (pictured below) is formed by two rows of two inclining unwrought pillarstones but unlike Our Lady’s Bed, it was entered at the east end. This unusual arrangement on Iniscealtra has also been compared to prehistoric tombs but the origins of the Confessional can be confidently traced to the early medieval period and it was likely constructed as a reliquary shrine.

Perhaps Our Lady’s Bed also housed saintly relics? Its location east of the church seems to reinforce this notion as it is typical of important early burials and shrines. For instance, the Confessional is a short distance northeast of two churches on Iniscealtra. Furthermore, it can be theorized that Our Lady’s Bed was initially associated with St Lomán who is traditionally believed to have established the church site on the island in the early medieval period. Fennel stated that “the Saint ‘mortified’ himself by spending sleepless nights in it [Our Lady’s Bed]”, although there is no proof that the structure is contemporary with the saint.

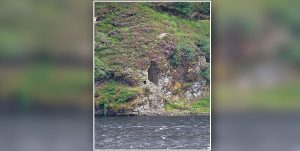

The various descriptions of the monument also bring to mind St Kevin’s Bed in Glendalough, Co. Wicklow, which is a small, manmade cave said to have been used in the 12th century by St Laurence O’Toole during Lent (pictured below). St Kevin’s Bed is just large enough for an adult to lie down inside. It is fascinating to note that in the 18th century expectant mothers would climb into St Kevin’s Bed in search of protection during pregnancy and childbirth.

As we have learnt, the layout of Our Lady’s Bed – as well as other penitential shrines like the Confessional and St Kevin’s Bed – would have forced the pilgrim into a penitent position, lying down or crawling on their knees. In this position inside Our Lady’s Bed, the pilgrim could potentially touch the saint’s relics (if indeed it was a reliquary monument as argued here), which would dispense protection and healing.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Devotion to Our Lady on Church Island

At some point devotion to the local saint on Church Island was seemingly sidelined by the cult of Our Lady as indicated by the name “Our Lady’s Bed”. This move is not surprising when we consider the trend in late medieval Europe of devotions made by pregnant women to Mary, mother of Jesus, for a safe delivery.

>>> READ MORE: Church Island on Lough Gill: its history and archaeology

In addition, it seems that in the late medieval period Church Island was possibly encompassed in the lands owned by the Cistercian foundation of Boyle Abbey, Co. Roscommon. Boyle Abbey was also known as St Maria Virginis (St Mary the Virgin), which indicates the strong devotion by this order to Our Lady. In fact, in the medieval period, the Ave Maria (Hail Mary) was one of the few prayers that the lay brethren of this order were permitted to learn.

There is a vague tradition linking the ecclesiastical site on Church Island with a female order. A letter written in 1836 by Ordnance Survey researcher Thomas O’Conor stated that “Tradition says that this [Church Island] was a nunnery”. This belief possibly stems from Church Island’s protective status for women and its long-established dedication to Our Lady.

Similarly, an entry in the Schools’ Folklore Collection (c.1937) states that there was previously a community of nuns on the nearby Cottage Island. In the medieval period, the church on Cottage Island was actually a dependency of the Premonstratensian order based at Holy Trinity abbey in Lough Cé and interestingly adoration to the Virgin Mary was central to Premonstratensian life. There is no definitive evidence supporting the idea that female orders resided on these two neighbouring islands but the folklore possibly hints at a strong emphasis on devotion to Our Lady and female-centred rituals in the general Lough Gill area.

If any of our readers have information regarding Our Lady’s Bed, please comment below.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Subscribe to the Irish Heritage News newsletter and follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram for all the latest heritage stories.

READ NOW

➤ Your essential visitor’s guide to Lough Gill

➤ Church Island on Lough Gill: its history and archaeology

➤ Could Church Island be Yeats’ treasured “Lake Isle of Innisfree”?

➤ Cottage Island on Lough Gill: its history and archaeology

Anglo-Celt, 21 Mar. 1885.

Archaeological Survey of Ireland, RMP SL015-096003-.

[https://maps.archaeology.ie/

HistoricEnvironment]

Fennell, W.J. 1904. ‘Church Island, or Inismore, Lough Gill’. Ulster Journal of Archaeology 10, pp.166-69.

Fosbroke, T.D. 1817. British Monachism, or Mannners and Customs of the Monks and Nuns of England. London, p.39.

Grose, F. 1791. The Antiquities of Ireland. Vol. 1. London, pp. 58-9.

Kilgannon, T. 1926. Sligo and its surroundings.

Lewis, S. 1837. A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland. Vol. 2. London.

Lewis, S. 1840. A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland. 2nd ed, vol. 1. London.

McCarthy, B., O’Leary, C. and Wallace, P. 2017. ‘Inis Cealtra: appendix 2 detailed support material’. In Inis Cealtra: Visitor management and sustainable tourism development plan. Clare County Council.

McParlan, J. 1802. Statistical Survey of the County of Sligo. Dublin, pp.103-04.

Ó Riain, P. 2011. A Dictionary of Irish Saints. Dublin.

O’Rorke, T. 1890. The History of Sligo: Town and County. Vols 1–2. Dublin.

Ordnance Survey Letters for County Sligo (1836).

[http://www.askaboutireland.ie/aai-files/assets/ebooks/OSI-Letters/SLIGO_14%20F%2014.pdf]

Penrose’s Pictorial Annual, 1908–09, vol. 14.

Schools Folklore Collection.

[https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes]

Wood-Martin, W.G. 1882. History of Sligo, county and town, from the earliest ages to the close of the reign of Queen Elizabeth. Vol. 1. Dublin.

Wood-Martin, W. G. 1887. ‘The rude stone monuments of Ireland (continued)’. Journal of the Royal Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland 4th series, vol. 8(71/72), pp.123-5.