Why would a crozier and a bell have been depicted on the Killinaboy slab? What was the inspiration behind the carvings of these precious early medieval relics?

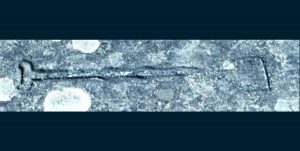

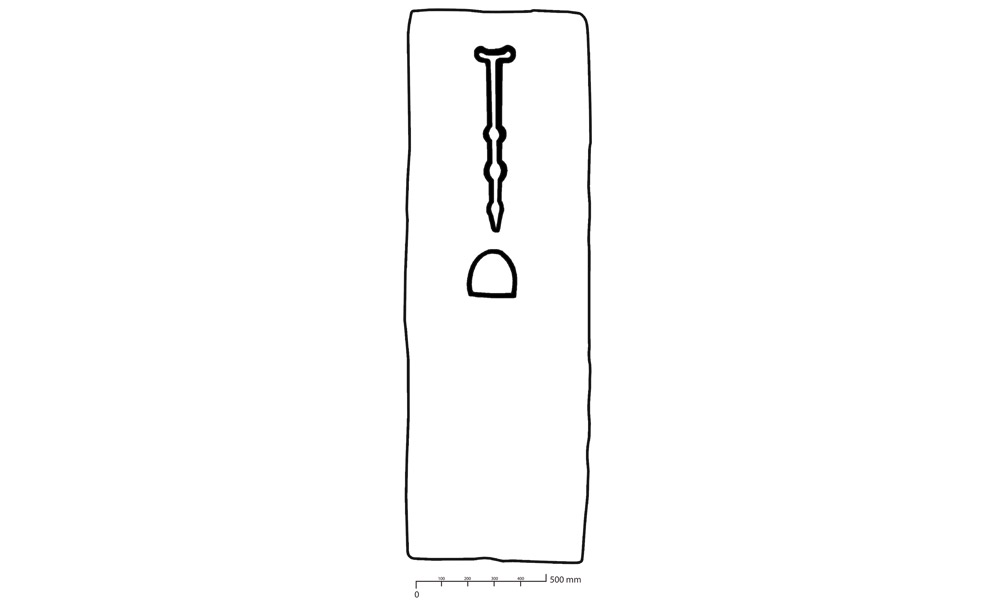

Located in the southwestern corner of Killinaboy early medieval church site, in north Clare, is a grave-slab deeply incised with an unusual carving. It seemingly depicts a tau-shaped crozier and a bell. The date of this large slab, measuring over 2m long, is uncertain but the 13th or 14th century seems plausible.

The tau crozier

A crozier is a type of staff carried by a bishop or abbot as a symbol of pastoral office and authority. In Western Christianity, the head of the crozier was often shaped like a shepherd’s crook but in the Eastern Church, the head was more commonly tau-shaped, while the oldest croziers from Ireland typically had a drop-head. However, the crozier featuring on the Killinaboy slab is tau-shaped.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

“Tau” is a T-shaped letter in the Greek alphabet, which was symbolically important to early Christians for a number of reasons. In time, the symbol became most closely associated with St Anthony of Egypt. Tradition holds that in the latter years of his life, the saint used a tau-shaped crutch. In the 12th century, the tau was selected as the symbol of the Order of Hospitallers of St Anthony (the Antonines) in France. At around the same time or a little earlier, tau-shaped croziers were being used by some high-ranking clergymen.

The tau crozier was introduced to Ireland probably in the 12th century, though surviving examples are very rare. Irish croziers sometimes encased a wooden staff, often a relic of a saint. In this way, the croziers operated as reliquaries. Even those that did not encase relics became intrinsically linked over time with the holy clerics that carried them.

The Kilkenny Archaeological Society tau-shaped crozier head (pictured above) could date to the early 12th century. This piece is of interest in the context of the Killinaboy carving because it has two upward curving seal heads, one at each end of the crossbar. As we can see, the crossbar of the Killinaboy tau carving displays similar curvature.

Part of the reason why the Killinaboy carving can be recognized as a crozier is that its shaft has three evenly spaced bulbous projections or knops. The knops indicate that the original crozier represented by this carving was manufactured in bronze.

The Killinaboy carving is arguably the only depiction of a tau crozier on an Irish grave-slab. While the tau crozier was also fairly unusual within the broader context of medieval stone craftmanship, it was reiterated locally on other types of sculpture: tau croziers feature on two 12th-century high crosses in north Clare (the Doorty Cross at Kilfenora and Tola’s Cross at Dysert O’Dea), and most notably the 12th-century freestanding sculpture from Roughaun Hill, just 2km away, is T-shaped (pictured below). Like on the Killinaboy carving, the ends of the crossbar of the Roughaun sculpture curve upwards.

It seems likely then that the various carvings in north Clare – including that on the Killinaboy grave-slab – portray the same venerated object: a tau crozier that was kept locally and clearly inspired sculptors for centuries. This relic could have been brought to the various church sites in north Clare during pilgrimage processions.

RELATED:

Although relatively unusual, the tau crozier does feature on medieval sculpture in other parts of Ireland too. For example, two types of croziers – tau-headed and spiral-headed – are carved on a cross from Broughanlea, Co. Antrim.

Rectangular grave-slabs and tombstones from Kilfenora (Clare), Labbamolaga (Cork) and Boyle Abbey (Roscommon), all compare well with the Killinaboy slab as they each carry a carving of a crozier, sometimes featuring knops, though none are tau-shaped.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

The handbell

The outline hemispherical shape carved beneath the crozier on the Killinaboy slab is possibly a representation of a handbell. It was not uncommon for bells to be depicted on gravemarkers, possibly because bell-ringing featured at funerals, but such gravemarkers are usually much later in date than the present slab.

One of the earliest descriptions of the slab comes from Rev. Philip Dwyer who noted in 1878:

“At the western side of the crowded graveyard is a flag slab with a curious symbolical emblem for the parish clerk … exhibiting a bell attached to a strap with which he rang the people to prayers, perambulating the parish.”

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

In the early 20th century, the Limerick antiquarian T.J. Westropp recalled on several occasions a legend that the Killinaboy bell was concealed in a “swampy patch” or “marsh” south of the church site. Unfortunately, it is not clear if he was referring to a handbell or a large church bell. But, in 1938, the following folk story was recorded in the Schools Folklore Collection:

“Nearly three hundred years ago English soldiers came to Kilnaboy, to plunder the Church. An old woman lived in a little house near by and when she heard that they came to plunder the Church, she went into the Church secretly and took a gold bell which it possessed because she was afraid they would take it. She took the bell and buried it in the soft ground in Riase Mór and it is said that she died and told her secret to nobody.”

This story clearly refers to a portable bell, probably a handbell. Notably, 12th-century copper alloy handbells are known to derive from the nearby early medieval church sites of Rathblathmaic and Kilshanny.

It has been suggested by a number of archaeologists that the bell from Kilshanny (also called the Bell of St Cuana) in particular could have inspired the carving at Killinaboy. This bell, now in the British Museum, may have originally been a drinking cup or chalice, and was subsequently refashioned as a bell; this idea is supported by the presence of three uneven features and a hole at the top of the object, possibly marking the point at which the missing stem of the chalice was attached.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

The tau-and-bell combo

Bells, staffs and croziers were often associated with Irish saints and later became the insignia of early bishops. Croziers are known to have accrued special functions in medieval Ireland. Some had a legal role even into modern times. For example, in the early 19th century it was recorded that St Grellan’s crozier from Ahascragh, Co. Galway, was still used for oath-swearing.

Hand bells were used by the early Church for timekeeping and in rituals. For instance, the processional exhibition of relics was accompanied by bell-ringing. Over time the bells were themselves considered relics, often connected with an early saint, such as the Kilshanny bell which is traditionally linked with St Cuana. Westropp in 1900 recorded that this bell “was used to swear upon, and was reputed to twist the mouths of perjurers to one side”.

Practices such as oath-swearing may have necessitated the movement of the prized bells and croziers throughout their local regions. Many miracles were attributed to them and they were much venerated by the people.

The Killinaboy slab is not the only medieval carving known to display both a crozier and a bell. Early medieval carved stones at Killadeas and White Island (both in Fermanagh), and the lintel stone of the doorway of the Priests’ House at Glendalough (Wicklow), all depict clerics carrying bells and staffs/croziers, though none are tau-shaped.

The dual symbolism could indicate that the Killinaboy slab marked the grave of some sort of cleric. This is especially likely when we consider that the head of the east/west oriented slab is to the east in contrast to the typical arrangement for medieval graves which saw their heads to the west. But sometimes graves holding the remains of priests and bishops were oriented in the opposite way, with their heads to the east, so that they could watch over their flock. This could explain the “upside-down” orientation of the Killinaboy slab, which distinguishes it as a special grave.

Sign up to our newsletter

We have already learnt that the Order of Hospitallers of St Anthony (the Antonines) adopted the tau symbol. Interestingly bells also became associated with the order, due to the practice of placing bells on their pigs. The Antonines also rang bells to announce their presence.

The most famous confraternity associated with the Antonines was that of the Knights of St Anthony, founded in 1382 by Albrecht II of Bavaria. Significantly the Knights of St Anthony wore a gold tau-shaped amulet from which a small bell hung. In the late medieval period, pendants cast in bronze, copper or lead alloy and purchased by pilgrims as souvenirs often featured this conjoined tau-and-bell symbol. This combination of symbols also appeared on other forms of jewellery, including rings. These pendants and rings are illustrated in several pieces of late medieval artwork.

By the mid-13th century, Antonine foundations had spread to London and York, and had adopted the rule of St Augustine. Of course, we know that there were Augustinian establishments in the north Clare area (including at Kilshanny), and it is quite possible that some conjoined tau-and-bell pilgrims’ pendants found their way there.

While this artistic parallel of the tau-and-bell combo is interesting to explore, earlier Irish dedicatory trends involving relics which took the form of bells and croziers should not be dismissed as the likely influence for the Killinaboy carving. What distinguishes this carving from the Antonine-inspired jewellery is that this tau clearly represents a crozier and must have been motivated by familiarity with such an object.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Killinaboy: an important repository for relics

Killinaboy is a medieval church foundation with some early features surviving, including the stump of a round tower. The church is mainly a late medieval construction but preserves features of an earlier church, including a huge double-armed cross protruding in relief from the west gable wall. The double-armed cross may be key to understanding the grave-slab carvings.

Byzantine reliquaries, sometimes containing a fragment of the cross on which Christ was crucified (the “True Cross”), were often fashioned in the shape of a double-armed cross. The presence of a double-armed cross on the gable of the church at Killinaboy has led to the belief that the building was used to store precious relics, perhaps even a relic of the True Cross, fragments of which were in circulation in Ireland in the medieval and post-medieval periods.

But maybe the church also housed locally important relics in the shape of a tau crozier and a handbell. The various relics would have been preserved by hereditary keepers of the church’s property (usually descendants of clergy). The striking double-armed cross could have operated as a beacon to signal their presence as it occupies a prominent position overlooking the road from Corofin to Kilfenora, which corresponds to the ancient “Bóthar na Mac Ríogh” (the King’s Sons Road).

All of the relics are now lost or their connection with Killinaboy is tentative. Some may have been removed as early as 1573 when, as the Annals of the Four Masters tell us, a war broke out among the Dalcassians and “some of their people carried utensils and spoils out of the church of Cill-inghine-Baoith [Killinaboy]”.

Sign up to our newsletter

Subscribe to the Irish Heritage News newsletter and follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram for all the latest heritage stories.

READ NOW

➤ Killinaboy’s disappearing and re-appearing tau cross

➤ St Tola’s high cross – an early medieval masterpiece at Dysert O’Dea

➤ The children’s burial ground in Drumanure, Co. Clare

➤ Bandle stone at Noughaval – a remnant of an abandoned settlement and market in Clare

➤ Cloheen graveyard, Co. Limerick: evidence of its medieval past

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Archaeological Survey of Ireland, RMP CL017-020005-.

Anon. 1854. Proceedings and Transactions of the Kilkenny and South-East of Ireland Archaeological Society 3(1), pp.129-41.

Bourke, C. 2000. ‘The bells of Saints Caillin and Cuana: two twelfth-century cups’. In A. P. Smyth (ed.) Seanchas: Studies in early and medieval Irish archaeology, history and literature in honour of Francis J. Byrne. Dublin, pp.331-40.

Bourke, C. 2008. ‘Early ecclesiastical hand-bells in Ireland and Britain’. Journal of the Antique Metalware Society 16, pp.22-8.

Dwyer, P. 1878. The Diocese of Killaloe from the Reformation to the Close of the Eighteenth Century. Dublin.

Harbison, P. 1976. ‘The double-armed cross on the church gable at Killinaboy, Co. Clare’. North Munster Antiquarian Journal 18, pp.3-12.

Harbison, P. 2012. ‘Twelfth-century pilgrims the Burren’s first tourists? Part 2 – high crosses and a ‘T’- or tau-shaped crozier-reliquary’. Burren Insight 4, pp.16-17.

Husband, T. B. 1992. ‘The Winteringham tau cross and Ignis Sacer’. Metropolitan Museum Journal 27, pp.19-35.

Jones, C. 2004. The Burren and the Aran Islands. Cork, pp. 136-7, 140-41.

Mac Mahon, M. 2000. ‘The cult of Inghin Bhaoith and the church of Killinaboy’. The Other Clare 24, pp.12-17.

Murray, G. 2007. ‘Insular-type croziers: their construction and characteristic’. In R. Moss (ed.) Making and Meaning in Insular Art: Proceedings of the fifth international conference on Insular art. Dublin, pp.79-94.

Ó Floinn, R. 1990. ‘Two ancient bronze bells from Rath Blathmach, Co. Clare’. North Munster Antiquarian Journal 32, pp.19-31.

Schools’ Folklore Collection, vol. 0614, p.151.

[https://www.duchas.ie/

en/cbes/4922359/

4874033/5075923]

Westropp, T. J. 1900–02. ‘The churches of County Clare, and the origin of the ecclesiastical divisions in that county’. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 3rd series, vol. 6(1), pp.100-80.

Westropp, T.J. 1909. ‘Miscellanea: the termon cross of Kilnaboy, County Clare, sketched in 1854’. Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 39, pp.85-88.

Westropp, T. J. 1911. ‘A folklore survey of County Clare (continued)’. Folklore 22(3), pp.332-41.