This is the story of the horrific Maumtrasna massacre and how a local man was cruelly put to death for a crime he didn’t commit.

Maumtrasna massacre

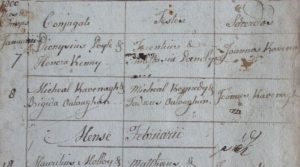

On 17 August 1882, five members of the Joyce family were killed in a savage attack as they slept in their beds in the remote valley of Maumtrasna, near the Mayo/Galway border, in an area known as Joyce Country. The victims were John Joyce, his wife Brighid, his mother Mairéad and his children Peigí and Micheál. Another son, Patsy, aged nine or ten was badly beaten but survived.

Patsy’s older brother, Mairtín, had been working as a farmhand in a neighbouring parish and fortunately, he was away from home that night.

It was presumed that the motive for the attack was connected with stealing sheep.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

The murders were described in the Irish newspapers of the time as “foul”, “dastardly”, “brutal”, “bloody” and “one of the blackest pages of our crime history” (Freeman’s Journal, 15 Dec. 1882), while a British newspaper called the locals “scarcely civilised beings … far nearer to savages than any other white men” (The Spectator).

Eyewitnesses

Soon after the murders, information given to the police by Anthony Joyce led to the arrests of ten local men. Anthony claimed that he was woken on the night in question by dogs barking and that he saw a band of men proceeding to John Joyce’s house, whom he followed and then watched as they entered the house.

He identified the following men as part of the murderous band: Anthony Philbin, Thomas Casey, Thomas Joyce, Patrick Joyce of Shanvallycahill, Patrick Joyce of Cappancreha, Martin Joyce, Myles Joyce, John Casey, Patrick Casey and Michael Casey.

Sign up to our newsletter

This story was corroborated by his brother John Joyce of Derry and John’s son Patrick, who also claimed to have followed the men.

Soon Anthony’s story was also supported by two of the men arrested, Philbin and Thomas Casey who became informers (approvers) for the Crown in the trial that ensued. While Philbin claimed he was ignorant as to the nature of the errand when they set out that night, Thomas Casey explained that the men were working under the orders of two others, Nee and Kelly, who were not in custody, and that these two were the true architects of the massacre.

The trial

The trial of the eight men spanned eight days. Some of the accused could neither speak English nor understand it but their trial took place entirely in English and the young solicitor defending the accused did not have a word of Irish. At this juncture in history, an Irish person who denied all knowledge of the English language was viewed by officials with scepticism and his/her “ignorance” of the language was seen as a ploy to subvert the judicial process.

An Irish translator, Head Constable Evans, was to communicate the proceedings of the trial to the accused but it seems that his services were employed inconsistently.

Throughout the trial, there were also discrepancies in evidence. The testimonies of the various witnesses differed with regards to the number of offenders, and while some stated that the men wore dark coats and did not obscure their faces, others swore that the assailants wore flannel waistcoats and had their faces blackened.

Some female relations provided alibis, often in Irish, for the accused, claiming that the men had not left their homes on the night in question. Other Irish-language evidence was seemingly suppressed by a prosecution eager for convictions.

One of the Irish-speaking prisoners was 45-year-old tenant farmer Myles Joyce, more commonly known among his own people as Maolra Seoighe. He was the third man arraigned and his case was spread over two days. Thomas Casey claimed that Maolra was one of the five men who forced in the door of the victims’ home. The jury took six minutes to return a guilty verdict. The Crown clerk informed Maolra of the verdict in English, which was translated into Irish by Evans after which a “change then came over the prisoner”. Maolra responded in Irish and the translator rendered it as follows:

“He leaves it to God and the Virgin above his head. He had no dealing with it; no more than the person who was never born … He slept in his bed with his wife that night, and he had no knowledge about it whatever. He is quite content with whatever the gentlemen may do to him but whether he is to be hung or crucified he is as free as he can be.” (Nation, 25 Nov. 1882)

It was reported that although Maolra exhibited considerable emotion in delivering this speech, he did not lose his self-control to the slightest degree. His heavily pregnant wife, Brighid, pleaded in Irish for mercy to be shown.

It had emerged during the course of the trial that the murderous scheme had been plotted in the house of Michael Casey; nearing 70 years of age, he was the oldest of the ten men.

On the eighth day of the trial, the court proceedings were brought to an abrupt end, when the counsel for the defence, Mr Malloy, withdrew the plea of not guilty for the remaining prisoners (Michael Casey, Patrick Joyce of Cappancreha, Martin Joyce, Thomas Joyce and John Casey) and in its stead, entered a guilty plea to the indictments of wilful murder.

>>> YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: The workhouse cemetery: “Clonakilty, God help us”

All eight men – including the three who had earlier pleaded not guilty but were found guilty – were sentenced by Judge Barry to be hanged on 15 December 1882. Malloy entered a plea for mercy for the five men who had admitted their guilt, arguing that they were acting under the orders of others. The judge explained that he would be glad if the Crown extended mercy and that this appeal would be sent to the Lord Lieutenant, the 5th Earl Spencer (great-granduncle of the current princes William and Harry), in whose power this rested.

It soon emerged in the press that Earl Spencer had ordered that rewards be paid to the Crown witnesses: Anthony and John Joyce each received £500, while Patrick received £250 (Belfast Newsletter, 11 Dec. 1882). £500 equated to over four years’ wages for a skilled tradesman in the 1880s. The men were also offered free passage out of the country but this was declined. These men were cousins of three of the men sentenced: Maolra and his brothers Martin and Patrick (Cappancreha).

On 11 December, a mere four days before the hangings were to take place, the death sentences for the men who had professed their guilt were reprieved. These five men were to escape with their lives but were to pass the remainder of it in penal servitude. In response, the Leinster Express (16 Dec. 1882) wrote that there was,

“nothing to justify Lord Spencer’s exercise of clemency respecting the five men … There is most assuredly nothing in the character of the crime of which the prisoners were guilty to command consideration. The murder was a daring and cruel execution of a cool-blooded decree pronounced by a secret society whose aims are to subvert the laws of the country.”

The five prisoners left the county jail in Galway on 14 December to be transported to a penal prison in England. The hangings of the other three men – Maolra Seoige, 35-year-old Patrick Joyce (Shanvallycahill) and 35-year-old Patrick Casey, all tenant farmers – were to go ahead as planned.

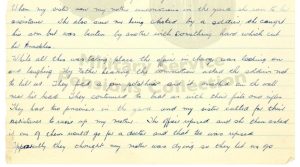

Maolra’s wife Brighid wrote the following letter to the Freeman’s Journal in English (a language she did not understand):

“Sir, I beg to state through the columns of your influential journal that my husband, Myles Joyce, now a convict in Galway jail, is not guilty of the crime … I earnestly beg and implore his Excellency the Lord Lieutenant to examine and consider this hard case of an innocent man, which leaves a widow and five orphans to be before long a dhrift [sic] in the world.”

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Imprisoned

The three men sentenced to death had been placed in individual cells in the hospital section of Galway prison. They were attended to daily by Fr Grevan (Greaven) and Fr Nevell, and were also visited by the Sisters of Mercy.

The day before the executions were to take place, Patrick Joyce and Patrick Casey confessed to having been part of the murder party but they insisted on Maolra’s innocence, stating that he had neither “hand, act, nor part” in the murders (Freeman’s Journal, 15 Dec. 1882). They added that some guilty men remained free. One of the men wrote in English, “It is the greatest murder in Ireland that ever was if he [Maolra] is hanged”.

Some hope was entertained that Maolra would not suffer the extreme penalty of the law. The statements of the guilty men were immediately sent to Spencer who responded with the cold insistence that “the law must take its course”. No reprieve was granted to Maolra. By then, Brighid had given birth to their daughter.

The executions

During this time, the hangman, William Marwood, was making his way from England to Galway prison. He had come prepared to execute eight men, only hearing that five of the sentences were commuted when he arrived in Galway. The scaffold had been made specifically for the execution of the eight men and was located in the hospital yard of Galway prison, a short walk from the prisoners’ cells. It was inspected carefully by Marwood who made some last-minute alterations.

On the morning of 15 December, Mass was celebrated at 7 o’clock in the prison chapel. Maolra was then led from his cell by two warders. He repeated in Irish the responses to the prayers which were being read by Fr Grevan.

Marwood placed the three men in a row, the tallest in the centre. Maolra pleaded desperately with the executioner as he placed the noose around his neck, “Cia’n fá mé chur ann báis?” (“Why should I be put to death?”). Up until the very end, he continued his protest of innocence in Irish:

“I am going before my God. I was not there at all. I had no hand or part in it. I am as innocent as a child in the cradle. It is a poor thing to take this life away on a stage; but I have my priest with me.”

The Galway Express reported that Maolra’s last words were “Arrah táim ag imeacht” (“I’m going”).

As Marwood stooped to draw the bolt, Maolra turned to make a fresh plea of innocence. In doing so, the rope got caught where his wrist was pinioned to his body; this apparently went unnoticed by the hangman. It was only when the drop fell that Marwood realized that something was wrong. The rope from which Maolra hung could be seen to vibrate and swing slightly. Marwood was seen muttering, “bother the fellow”. For a few minutes, he pushed the body with his boot, while pulling the rope with his hand backwards and forwards in order to disentangle it. “Through this fearful mishap it is believed that Myles Joyce’s death was a terrible one” (Nation, 23 Dec. 1882).

A F F I L I A T E A D

Maolra’s departure from this life was not straightforward. Patrick Casey and Patrick Joyce seemed to die without a struggle and the death register records the cause of their deaths as “Fracture of the neck being the result of hanging”, but Maolra’s reads “Strangulation being the result of hanging”. At a later inquest into the latter’s death, the jury wished to call Marwood but the coroner would not permit this.

The aftermath

Within a month of the executions, it was reported in the Kerry Independent (15 Jan. 1883) that Maolra’s ghost had appeared numerous times within the grounds of Galway prison and as a result, the matrons and wardens there had applied for transfers. Officials and soldiers alike claimed they had been followed by a “tall mystic figure”.

Please help support

Irish Heritage News

A small independent start-up in West Cork

Give as little as €2

Thank You

Soon after, one of the widows of the men executed and a brother-in-law of Maolra were accused of using intimidating language towards the Crown witnesses and were imprisoned. Subsequently, the witnesses were granted police protection. A couple of months later, a fight broke out in Boyle’s pub in Churchfield between Maolra’s relations and the witnesses, accompanied by five men from the Constabulary, during which the witness Anthony Joyce was severely wounded with a sword that “destroyed his nose” (Kerry Independent, 5 Mar. 1883).

In 1884, Thomas Casey, the approver (informer), told the Archbishop of Tuam, Dr John McEvilly, that he had caused the death of an innocent man, Maolra Seoighe, and the imprisonment of four other innocent men, which included Maolra’s two brothers. The archbishop sought an inquiry and lengthy debates ensued in the British parliament.

A F F I L I A T E A D

The cause of the Maumtrasna men was championed in particular by Tim Harrington, MP with the Nationalist Party. Harrington conducted his own inquiry, visiting the area and questioning locals and priests.

He discovered that the men had been convicted on the basis of perjured evidence, and as we know, the so-called witnesses were paid handsomely for their services to the Crown. While they had claimed that they had followed the murder gang on the night of the killings, it was apparently well known that Anthony Joyce had learnt about the murders for the first time the following morning on being told by his daughter while out working. The evidence given by Philbin, the other approver, did not tally with that given by the three Crown witnesses, and Thomas Casey’s most recent revelations differed from them all, as did other evidence that Harrington gathered from locals.

Harrington argued for justice in the House of Commons and raised concerns over Spencer’s influence in the trials. The Irish Executive, however, refused at every turn to make public the depositions of the other two men executed regarding Maolra’s innocence. Equally, they refused to undertake a full, public and independent inquiry.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

The pardoning

Maolra’s innocence is widely accepted and his wrongful execution was one of the most notorious miscarriages of justice in legal history in Ireland. In 2016, two members of the House of Lords, David Alton and the late Eric Lubbock, sought to have the case reviewed. Britain’s justice minister, Crispin Blunt, conceded that Maolra was “probably an innocent man” but he would not seek a pardon unless new evidence emerged.

In April 2018, the unprecedented posthumous pardoning of Maolra Seoighe was granted by President Michael D. Higgins. At the time, it was the only pardon to have been granted by the Irish government that involves a case that took place prior to the founding of the Irish state.

Advertising Disclaimer: This article contains affiliate links. Irish Heritage News is an affiliate of FindMyPast. We may earn commissions from qualifying purchases – this does not affect the amount you pay for your purchase.

READ NOW

➤ Fr Lorcán Ó Muireadhaigh and the founding of “An tUltach” (The Ulsterman) in 1924

➤ Clogagh: a small West Cork community transformed by the Revolution

Belfast Newsletter, 11 Dec. 1882, p.5.

Death records, Myles Joyce, Patrick Joyce and Patrick Casey, 15 Dec. 1882, HM Prison, Galway.

[https://civilrecords.irishgenealogy.ie

/churchrecords/images/deaths_returns

/deaths_1882/06381/4831810.pdf and https://civilrecords.irishgenealogy.ie

/churchrecords/images/deaths_returns

/deaths_1882/06381/4831809.pdf]

Freeman’s Journal, 22 Nov. 1882, p.2; 15 Dec. 1882, p.5; 1 Sep. 1884, p.2; 20 Sep. 1884, p.5.

Irish Times, 16 Dec. 1882.

Kelleher, M. 2018. The Maamtrasna Murders: Language, life and death in nineteenth-century Ireland. Dublin.

Kerry Evening Post, 22 Nov. 1882, p.2; 31 Jan. 1883, p.2.

Kerry Independent, 20 Nov. 1882, p.4; 15 Jan. 1883, p.4; 5 Mar. 1883, p.4.

Kerry Sentinel, 21 Nov. 1882, p.4.

Kerry Weekly Reporter, 3 Mar. 1883, p.3.

Leinster Express, 18 Nov. 1882, p.5; 25 Nov. 1882, p.5; 1 Nov. 1884, p 5; 16 Dec. 1882, p.5; 1 Nov. 1884, p.5.

Nation, 25 Nov. 1882, p.5; 16 Dec. 1882, p.4; 23 Dec. 1882, pp. 1 & 4; 20 Sep. 1884, p.16.

Ó Cuirreáin, S. 2017. Éagóir: Maolra Seoighe agus dúnmharuithe Mhám Trasna. Cois Life.

Wexford People, 22 Nov. 1882, p.5; 13 Dec. 1882, p.4.

2 Responses

a good site

Wow an interesting case