By Madeline Hutchins

Madeline Hutchins, great-great-grandniece of Ellen Hutchins, discusses the short life and scientific contributions of Ireland’s first female botanist, revealing her relentless dedication to botanical research amid personal challenges. New discoveries add further tangible connections to Ellen’s remarkable story.

Ellen Hutchins: her story & recognition

Ellen Hutchins (1785–1815), of Ballylickey on Bantry Bay in Co. Cork, is widely recognized as Ireland’s first female botanist. She was also an accomplished botanical artist. Her reputation as a botanist has always held firm in her specialist areas of study – seaweeds, lichens, mosses and liverworts – with her name appearing as a finder of many species in botany books and her specimens in major herbaria still used for scientific research and plant identification. However, outside of these botanical circles, her name and the story of her life and work were not known.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

It is only relatively recently that her story – of a determined young woman, botanizing alone in a remote but exceptionally beautiful part of Ireland, intent on increasing our understanding of some of the most challenging of plants – has drawn considerable interest.

Despite struggling with her own ill health and having onerous caring responsibilities for her mother and a disabled brother, Ellen acquired a high level of specialist knowledge in a difficult branch of botany. She found and prepared a huge number of specimens, wrote copious letters and notes, and produced hundreds of watercolour drawings. These were sent to a specialist community of botanists, including the most eminent names of the day. In her short time botanizing, Ellen found about 20 new species, some of which were named after her in recognition of her service to science.

The survival of a substantial collection of correspondence provides a very direct and intimate glimpse into Ellen’s story, which includes her letters to fellow botanists and two of her brothers, as well as those she received from botanists. Her correspondence with eminent botanist Dawson Turner in Great Yarmouth on the East Anglian coast of England lasted seven years (1807–14), and over 120 letters have survived. Their correspondence covers much more than the plants they were studying as a deep and strongly supportive friendship developed between the pair. One theme is the books and authors that Turner and Ellen were reading, including Dante, Walter Scott, Lord Byron’s poetry and the Life of Tasso.

>>> RELATED: Letters from 1812 written by noted botanist Ellen Hutchins explored in new podcast

Professor Michael Mitchell’s publication in 1999, Early Observations on the Flora of Southwest Ireland: selected letters of Ellen Hutchins and Dawson Turner 1807–1814 (Glasnevin Publishing), was a significant milestone in revealing Ellen’s story. Ellen was given an entry in the Dictionary of Irish Biography in 2009; then, in 2015, the bicentenary of her death, a festival was held in her honour in Bantry and a plaque was unveiled in the churchyard where she is buried in an unmarked grave.

The Ellen Hutchins Festival is now an annual event held during Heritage Week and is run by a non-profit organization based in Bantry; it features walks and talks celebrating Ellen’s life and work, botany and botanical art, as well as the heritage, landscape, biodiversity and beauty of Bantry Bay.

Sign up to our newsletter

New finds and letters

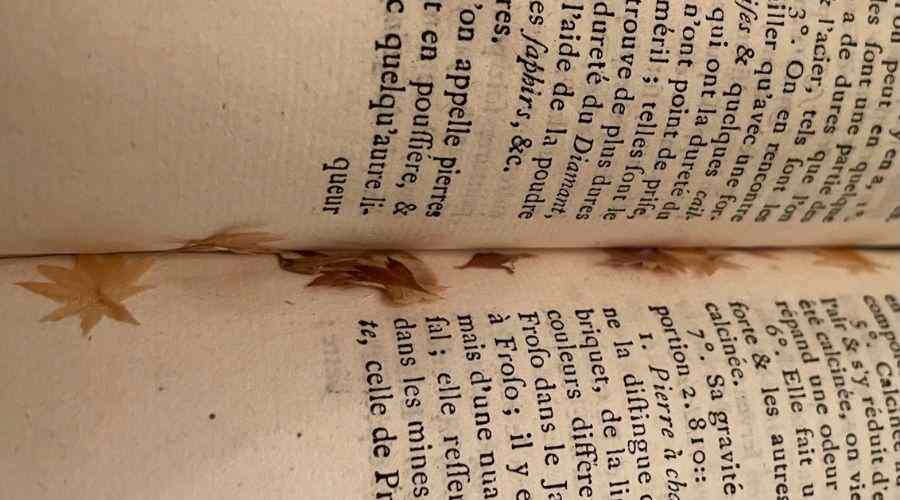

I’m still assembling information on Ellen’s story with regular new finds emerging, primarily letters and documents in public or private archives and family cupboards. While I have found many books of Ellen’s, including her copy of Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Aminta by Tasso and Dante (sent to her by Turner), none were on botany or natural history.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

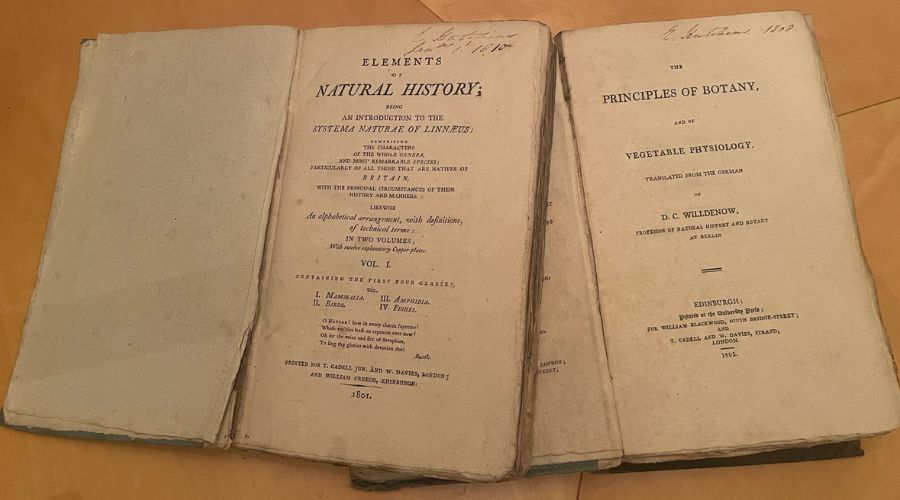

Therefore, the latest discoveries are very welcome: The Principles of Botany by Willdenow (1805) and Elements of Natural History by Charles Stewart (1801). Both have “E Hutchins” written in them and dates – “1808” in Willdenow and an exact date, “1st January 1810”, in the other.

Ellen delighted in seeing the details of a miniature world through her microscope and wrote of one particular seaweed: “I spent 5 days admiring it”. I sometimes find that reading a letter provides a similar window into another world and that it allows us to focus in on details and specific moments in Ellen’s life. In a letter to Dawson Turner on 5 January 1810, just four days after she penned her name and date in the Elements of Natural History book, Ellen wrote:

“How shall I thank you, my dear Sir, for your kind wish to gratify me by writing as soon as my little parcel arrived, & for the pleasure your letter gave me. Its arrival on New Year’s day I take as a good omen, & sincerely wish that this & many succeeding years may be productive of peace & health to you & those on whom your happiness depends. That you like the drawings is a great pleasure. Wherever you see any defect pray tell me that I may do better copies for you. I am not myself satisfied with the magnified parts of the Rivulariæ, but now that I have a better microscope if I can live till next season, you shall have much better magnified parts & I shall, I hope, be able to make some observations on the fruit which seems to me not of the same nature with that of Conferva gelatinosa. Think, my dear Sir, what a feast it was to have all those plants to examine & compose in one day. The impression it made & the reflections it produced I shall never forget…

I hope Mr. Hooker will soon give us the Jungermanniæ [his large work on liverworts]. What a delightful family they are. I often regret that Mr. Dillwyn has so completely concluded the Confervæ [his book on what was then a muddled genus of freshwater and marine algae, diatoms and bacteria]. Sometimes I think myself very ungrateful to feel dissatisfied when he has taught me all I know of that genus, but it is impossible not to feel regret. I am sorry to hear he is so plagued with law, of all earthly torments one of the worst. I hope you found the mosses in the last parcel interesting. All mosses are very much so, nothing delights me more than the sight of a great rock covered with a variety of mosses. In winter the rich shades of green they afford are very beautiful. I have a rock in my little flower garden, the north side of which is freely covered with mosses & ferns. I am sorry Mr. Woods was not as successful as he expected in Botany. I should think a traveller not likely to find a great deal unless he goes to some distant untried part of the world. Any country requires to be minutely examined & travellers seldom spend time enough at any one place to know what it produces [Woods had stayed in Killarney for a month or more].

Your letter by Captn. Mangin I have not yet received, but am in daily expectation of it, though letters & parcels are often long delayed they in the end are received in safety. I hope my last will not be as long on its journey as the two former ones.

Of late I have been much amused & occupied with shells, of which we have a better variety than I at first expected. Some I cannot satisfy myself about, & some rare ones I have got among others Venus triangularis finer than the figure represents, & being prettily coloured. You shall in some time have the best specimens I can procure of what our own shores produce. I have half blinded myself picking seashells out of sand.

Believe me, my dear Sir, very faithfully yours

E. Hutchins

Ballylickey

January 5th. 1810.”

There was a distinct seasonal pattern to Ellen’s botanical and natural history studies, with December, January and February used to catch up and plan ahead. During these months, she typically finished drawings, ordered or was given books, and the year before, on 21 January 1809, she wrote: “I have just procured a large store of drawing materials”. Winter also often brought illness to which she was very prone. In the same letter of 21 January 1809, Ellen stated:

“I should long since have answered your letter containing the mosses which I received above a month ago but that a few days after I wrote last to you I was attacked with a very severe illness from which I am now thank God recovering & though nearly free from pain I am much weakened. The mosses were a great treasure; they were all but two new to me.”

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Ellen’s letters show a lively use of language, lightness of touch and a lovely, confident writing style. She displays a great appreciation of beauty in plants and landscapes, referring to plants as “little beauties” or “treasures” and sometimes “friends”.

Natural pursuits

Ellen, like many botanists of her time, expanded her studies beyond botany to include sertulariae (a family of hydrozoans) and seashells, culminating in the discovery of two new seashell species. She observed that,

“our shores are too rocky to produce many species but we have immense banks of coral sand which is very useful & valuable for manure, with it we get many shells.”

Bantry Bay was very remote, hemmed in as it is by mountains, then with very poor-quality roads through them. We believe that Ellen probably never went to Cork city to visit its botanic garden or for any other purpose. She had a very small, but wonderfully diverse and rich, botanical world to explore, which had not yet been visited by other botanists – as Ellen said, “a distant untried part of the world” botanically.

Ellen, when her health and caring responsibilities allowed, was keen to get to the mountains and we know she ascended Sugar Loaf, Hungry Hill and Knock Boy – all considerable achievements for that era. In addition, she had the use of a boat, which enabled extensive exploration of Bantry Bay’s shores and islands. Often, she botanized alone or with the aid of a young boy or girl to help with her boxes and baskets.

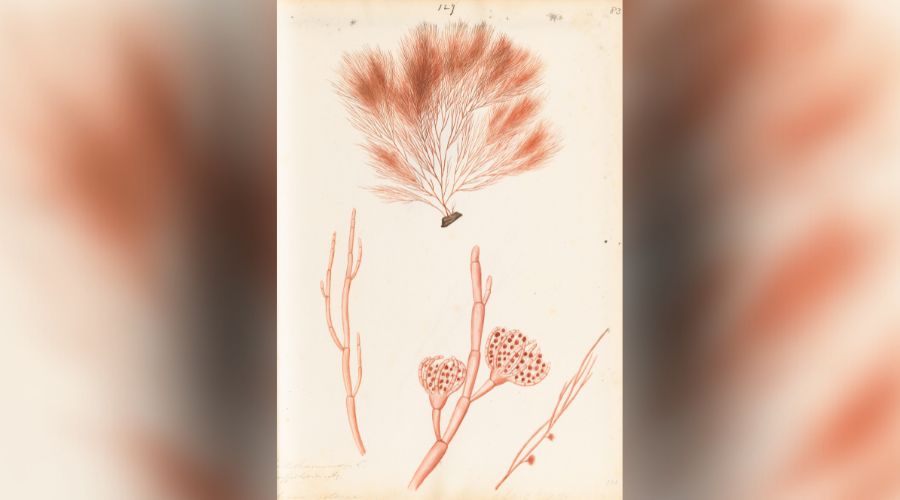

Botanical art & publications

While there are huge differences now in the equipment available, the process of spreading and drying seaweeds and plants to make specimens has hardly changed at all. Where there have been major changes is in the quality of microscopes, way beyond Ellen’s “better” one, as well as in the means of recording and sharing what specimens look like when fresh. Then, if Ellen found a new seaweed that lost its colour when collected, her only options were to describe it in words or capture it in a watercolour painting. Her skills in both were greatly admired by fellow botanists and aided in the development and sharing of knowledge about seaweeds.

In botanical art, much is the same now as then. Watercolour paper, pencils and paints have not undergone major changes other than removing toxic elements from the paints (making licking your brush much safer). Botanical art still serves science and the best of botanical plant portraits can give more information to today’s botanists than any photo.

Sign up to our newsletter

Ellen was adamant that, to be useful, botanical publications needed illustrations of each species. These were notably absent from the general botany books she had – Withering and Willdenow – but English Botany (covering all of Britain and Ireland) and the monographs that she contributed to on seaweeds and liverworts prided themselves in providing an illustration of each species.

Mosses and liverworts (Jungermanniae) held a special place in Ellen’s heart. In a letter of April 1813, Ellen wrote:

“Let me tell you how when I sat to rest my weary frame on a bank of moss I started up with pleasure at sight of Jungermannia viticulosa full of fructification & said to myself how glad Mr. T will be. I never felt more pleased than at finding it, so very interesting too.”

This was Ellen’s last active botanizing, as shortly after this, she became seriously ill.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Illness, death & an enduring legacy

Despite her deteriorating state, Ellen’s friendship and correspondence with Dawson Turner continued. Her last letter to him, in November 1814, ended very poignantly:

“I cannot write any more. I cannot read at all now or amuse my mind in any way & this is worse than pain to a mind once active & though ever struggling with disadvantages seldom unemployed. Send me a moss, anything just to look at.”

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Ellen died on 9 February 1815, just before her 30th birthday. Tributes to Ellen stressed her knowledge and her industry, her delight in sharing knowledge and being useful in helping others, also her generosity – exemplified by being willing to give away her last specimen of something very rare with no guarantee of finding another to replace it.

Ellen’s legacy is both the specimens held in major herbaria and also her story that provides a link to the past, resonates with the present and can, I think, influence the future.

Remembering Ellen Hutchins

Ellen is increasingly being given a place within accounts of Irish scientists, botanical artists and notable Irish women, with the most recent being in Patricia Butler’s book Drawn from Nature: the flowering of Irish botanical art and Gráinne Lyons’ Wild Atlantic Women and before those Botany & Gardens in Early Modern Ireland from Four Courts Press and Through her Eyes: a new history of Ireland in 21 women by Clodagh Finn. There is also the well-received historical novel A Quiet Tide by Marianne Lee. In 2022, an article on RTÉ Brainstorm assessed Ellen’s character and practice as a botanist against researcher qualities highlighted in a recent study published in Nature.

Ellen’s story is cited as an encouragement for girls to study science. Within the books for the Gill Education new Primary Irish Language Programme, Cosán na Gealaí, Ellen is highlighted as an exceptional role model for all children, particularly with regards to science and the environment. In September 2022, the HQ building of the Environmental Research Institute of University College Cork (UCC) was named the “Ellen Hutchins Building”, in recognition of her exceptional determination and dedication in her pursuit of scientific study against many odds.

While her modest nature would undoubtedly be shocked by all this attention, I hope Ellen would nonetheless approve of being useful as a role model.

Please help support

Irish Heritage News

A small independent start-up in West Cork

Give as little as €2

Thank You

Upcoming events & resources

The anniversary of Ellen’s death, 9 February, falls aptly between the new bank holiday for St Brigid’s Day and the International Day of Women and Girls in Science on 11 February. On Saturday, 10 February this year, the Environmental Research Institute of UCC is hosting an open house event in the Ellen Hutchins Reading Room of the Ellen Hutchins Building on the Lee Road. This gives you an opportunity to view the Ellen Hutchins’ archives, to make seaweed specimens and to try your hand at letter writing using early 1800s techniques.

On the dedicated website for the Ellen Hutchins Festival held in August every year, ellenhutchins.com, you can find transcriptions of much of Ellen’s correspondence, free resources on botany, a heritage trail and information on Ellen’s story, where the archives are held, the annual festival, a small biography of Ellen and a range of botany books.

Madeline Hutchins, a great-great-grandniece of Ellen Hutchins, is an organizer of the Ellen Hutchins Festival and a researcher of Ellen’s life and work.

READ NOW

➤ Letters from 1812 written by noted botanist Ellen Hutchins explored in new podcast

➤ How Cromwell’s Bridge in Glengarriff got its name

➤ Bishop Edward Synge and his “dear giddy brat”

➤ Ireland’s tradition of dry stone wall construction earns UNESCO recognition

➤ From Mayo to Buckingham Palace: the legacy of Tom Mulloy, an untrained “genius”

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

One Response

Ellen Hutchins initially was encouraged by Dr Whitley Stokes (1763-1845) of Trinity College, Dublin and Sneem, Co. Kerry and also mentored by Thomas Taylor MD of nearby Dunkerron, Kenmare, (her cousin via their Palmer ancestry). Taylor was born on a boat on the Ganges; he was an amateur botanist, with several publications on mosses and lichens and a friend of William Hooker and Dawson Turner. In 1815 Hooker married and spent his honeymoon in Ireland, staying with Taylor in Dublin and meeting Stokes.

Thomas Taylor found that work was getting in the way of his botanising so he quit his medical practice and moved to his Kerry home. At the outbreak of the Famine he was instrumental in setting up Kenmare’s Fever Hospital. In May 1847 he wrote to Hooker “Our distress in this district is grave indeed….100 die daily, painfully of Fever and Dysentery…. which would not have the same force but for the previous starvation. At the Poor House I attend daily 200 in the Epidemic. I am unassisted. More than 40 medical officers in Union Workhouses have already perished of Fever caught in the discharge of their duties. Assuredly my turn cannot be very distant.” He again wrote to Hooker in similar terms during September. He was prescient, he paid the ultimate price, dying of fever on February 4th, 1848. His herbarium is now in Harvard University