In the first half of the 19th century, an Irish priest so impressed the pope that it led to the transfer of St Valentine’s remains from Rome to Dublin’s Whitefriar Street Church – an event that inspired fervent devotion among some but also provoked a sectarian backlash. Today, the relics continue to attract visitors from around the world.

In the 1830s, Pope Gregory XVI decided to gift a Dublin priest, Fr John Spratt, a reliquary containing the corporeal relics of St Valentine, a 3rd-century martyred Roman cleric.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Fr John Spratt and Whitefriar Street Church

Fr John Francis Spratt was ordained in 1820 and shortly after joined the Dublin community of Calced Carmelites on Cuffe Lane. A prominent figure in Dublin, he was known for his work as a temperance reformer and philanthropist, founding several charitable institutions, including an orphanage, refuge and a number of free schools.

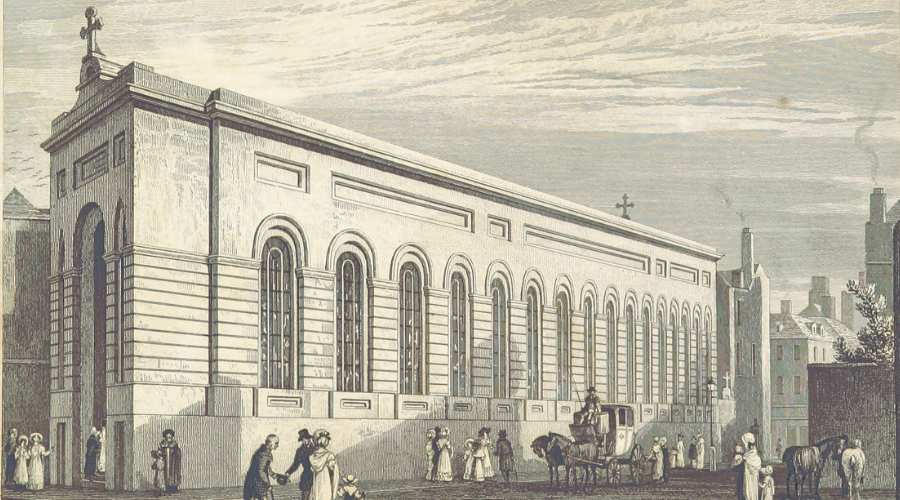

In about 1825, Spratt secured a site for a new church in Dublin city on Whitefriar Street where a medieval Carmelite priory had once stood. The project was led by esteemed architect George Papworth. The Church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, as it is officially named, was completed in 1826 and was consecrated the following year. Whitefriar Street Church was under Spratt’s administration as prior of the order.

All that remains of the original structure, designed by Papworth, now forms the southern aisle, as the church underwent significant remodelling, extensions and renovations over time.

How did St Valentine’s relics come to Dublin?

In 1835, during a visit to Rome, Fr John Spratt’s preaching skills drew large crowds and attracted the attention of the city’s elite, including the pope himself. Impressed by Spratt’s efforts, Pope Gregory XVI agreed to send the relics of St Valentine to the Irish priest as a token of esteem.

On 10 November 1836, St Valentine’s reliquary arrived in Dublin, accompanied by a letter from Cardinal Carlo Odescalchi, the Vicar General of the Diocese of Rome, confirming the authenticity of the relics contained within the reliquary.

Sign up to our newsletter

Dated 29 January 1836, the letter describes how, on 27 December 1835, the blessed body of St Valentine, the martyr, was removed from the cemetery of St Hippolytus on the Via Tiburtina, together with a small vessel tinged with his blood. The letter goes on to explain that the relics were subsequently placed in a wooden case, covered with painted paper, securely closed, tied with a red silk ribbon and sealed with official seals. The letter added that the relics were now being entrusted to Fr John Spratt.

A solemn procession carried St Valentine’s reliquary from North Wall to Whitefriar Street Church, where Archbishop Murray of Dublin received it and presided over a high Mass in celebration.

A F F I L I A T E A D

Around the time the relics arrived in Dublin, a printed handbill was circulated throughout the city, informing the public that the remains of St Valentine had been deposited in the Carmelite chapel on Whitefriar Street. It also announced that the pope had granted a plenary indulgence for those who said certain prayers before the sacred relics. Large crowds gathered in the church in the days that followed.

>>> READ MORE: Custom of sending Valentine cards temporarily died out in early 1900s Ireland

The relics caused a sensation among non-Catholics also. A week later, a letter from the Protestant Rev. C. M. Fleury, published in the Dublin Record, described his visit to Whitefriar Street Church. The letter explains that he was led by an attendant to the high altar, where a grating was fixed underneath it and through this grating, he saw what appeared to him to be a coffin case – the reliquary – covered with velvet and fringed with gold lace.

There, Fleury observed a group of worshippers lying face down on the ground, pushing their fingers through the grating to rub gloves and fragments of linen cloth against the velvet covering of the reliquary in the belief that the cloths would be imbued with healing properties.

| a system of iniquity

Fleury, deeply disturbed by what he had observed, denounced the Catholic practice of venerating relics:

“Perfectly disgusted with the whole business, I left the chapel immediately and thought it right to give publicity thus to what I had witnessed. When such an imposition can be fearlessly practised on Roman Catholics of every rank by their priests, I would ask what may they not be inclined to believe and do by the same masters? When such superstition openly prevails, are we not guilty, in the most awful degree, if we do not use every honest means in our power, by scriptural education and controversial preaching, to deliver our poor fellow countrymen from such a system of iniquity?”

Fleury’s remarks reflect the sectarian tensions of the time, less than a decade after Catholic emancipation.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Whitefriar Street Church continued to draw large numbers of visitors, but eventually, interest in the relics waned, particularly after the death of Fr Spratt in 1871.

Many recent reports claim that the relics of St Valentine were lost for decades after Spratt’s death until they were “rediscovered” in the 1940s. However, this may not be entirely accurate, as both the Irish Catholic and the Irish Independent published reports on the relics in 1906, and other Irish newspapers mentioned them in the 1910s and 1920s, with none suggesting that the relics had been lost. What these reports make clear is that the relics were not widely known, even among Dubliners.

According to a 1956 article in the Irish Independent, the relics had remained under the high altar until 1936, when they were placed under a temporary altar during restoration works and later stored in the community oratory (other reports say the sacristy).

St Valentine’s shrine at Whitefriar Street Church

St Valentine’s relics were restored to prominence at Whitefriar Street Church in 1956 as part of a major restoration programme. A new side altar and shrine were erected to house and display the reliquary, which features a statue of St Valentine, dressed in the red vestments of a martyr and holding a crocus – a work by Irish sculptor Irene Broe.

The reliquary’s inner cedar box containing the relics has never been opened and its seals remain unbroken to this day. The box is believed to contain the partial remains of St Valentine, though it is not claimed that all of the saint’s remains are present. Some recent reports have described these relics as his heart, but there is no evidence to support this claim. (More details on other relics associated with St Valentine below.)

>>> READ MORE: St Brigid’s relics returning to Kildare after a millennium

The shrine can be visited all year round and attracts people from around the world. A book in the church contains countless petitions addressed to St Valentine. For those hoping to visit, Whitefriar Street Church is located between Aungier Street, Whitefriar Place and Whitefriar Street – just a 5-minute walk from St Stephen’s Green.

St Valentine’s Day at Whitefriar Street Church

The most popular day to visit St Valentine’s relics at Whitefriar Street Church is, unsurprisingly, 14 February, St Valentine’s feastday. On this day, the reliquary is moved from its usual position at the side altar to the high altar for veneration. Special Masses are celebrated, which include a blessing of wedding rings.

Please help support

Irish Heritage News

A small independent start-up in West Cork

Give as little as €2

Thank You

Visitors come for many reasons: some seek blessings for upcoming marriages, others hope to find love and some visit to honour the memory of a deceased loved one.

Who was St Valentine?

Now regarded as the patron saint of lovers, the historical details surrounding St Valentine, a 3rd-century martyr, are complicated by the existence of several early saints and martyrs of the same name. The Roman Martyrology lists two Valentines from Italy, both with feastdays on 14 February.

One refers to a priest who, after performing healing miracles, was beheaded on the Via Flaminia, an ancient Roman road, during the reign of Emperor Claudius II. The other refers to Bishop Valentine from Terni – formerly Interamna, a town in Umbria in central Italy – who, after performing a healing miracle, was beaten, imprisoned and ultimately beheaded on the orders of Placidus, the prefect of Rome.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Both were decapitated supposedly on 14 February, within about 60 miles of each other and while various years are stated, these typically centre on the late 3rd century (around the 260s and 270s). The similarities between the two stories have led some to argue that they refer to the same man. One possibility is that two cults – one based in Rome and the other in Terni – grew up around the same martyr, but the stories became confused and diverged over time.

Where was St Valentine originally buried?

There is considerable uncertainty surrounding St Valentine’s original burial place and the current location of his remains, with numerous churches laying claim to his relics.

One widely accepted tradition holds that St Valentine was initially interred in the catacombs along the Via Flaminia. Catacombs served as underground cemeteries for early Christians, especially during periods of persecution. At some point in the medieval period, the saint’s relics were reportedly transferred to the Church of St Praxedes (Santa Prassede) in Rome.

Other accounts, particularly from Irish sources, state that St Valentine was buried in the cemetery of St Hippolytus (Hippolitus) along the Via Tiburtina, another ancient Roman road.

All these places are in relatively close proximity to one another, in and around Rome, contributing to the confusion surrounding the saint’s burial site.

A F F I L I A T E A D

Another popular tradition contends that St Valentine was buried in Terni either immediately after he met his demise on the Via Flaminia or shortly thereafter, and today, those remains are housed in the Basilica di San Valentino in Terni. The earliest church on the site was built over what many believe was the saint’s original tomb.

Whatever the case, relics attributed to St Valentine have become scattered across Europe. His skull is kept in the Basilica of Santa Maria in Cosmedin in Rome. In San Antón Church in Madrid, Spain, his reputed relics have been encased in a glass display since the late 18th century. A church in Glasgow, Scotland and a basilica in Prague, Czech Republic, also claim to possess portions of his remains. Other places, such as Savona (Italy), Slovakia, Poland, France, England and the Greek island of Lesbos, make similar claims. And then, of course, there are the relics housed in Whitefriar Street Church in Dublin.

St Valentine’s Day and its association with love

St Valentine has been venerated on 14 February in Western Christianity since at least the early medieval period, but it is not clear how long his feastday has been associated with romantic love.

While some argue that the saint’s possible role in secretly performing outlawed marriages between Christians laid the foundation for this association, there is no historical evidence for this in early accounts of his life. Instead, these medieval texts focus on the miracles he performed, the conversions to Christianity he inspired and the martyrdom he suffered as a result.

Sign up to our newsletter

Attempts to link the origins of Valentine’s Day courting customs with Lupercalia, a pagan Roman fertility festival held in mid-February, have long been debunked by historians as lacking a credible basis, although the outdated theory continues to be perpetuated in the press and on social media.

Instead, modern academic research has shown that the association between St Valentine’s Day and expressions of romantic love is probably a relatively recent development. (Though, of course, Christian couples have always invoked saints to intercede for blessings upon their marriages, and surely St Valentine was no different in this regard.)

A widely cited theory, advanced in particular by the late Dr Jack B. Oruch, an English professor at the University of Kansas, traces the romantic connotations of Valentine’s Day to Geoffrey Chaucer’s 14th-century poem Parliament of Fowls. In it, Chaucer describes birds gathering on St Valentine’s Day to choose their mates.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Other 14th and 15th-century poets soon followed Chaucer’s lead, employing the Valentine love theme. By the 15th century, the word “Valentine” had come to signify a sweetheart. A famous early example appears in a letter written in February 1477, in which Margery Brews of Norfolk refers to her soon-to-be husband John Paston III as her “right well-beloved Valentine” and signs it “your Valentine, Margery Brews”. This shows the growing link between St Valentine’s Day and love and courtship.

In some regions, by the 18th century, it had become common to exchange small tokens of affection, handwritten notes or poems on St Valentine’s Day. By the 19th century, this practice evolved into sending Valentine cards, establishing the custom as we know it today. Read about the history of Irish Valentine’s Day card-giving customs here.

Advertising Disclaimer: This article contains affiliate links. Irish Heritage News is an affiliate of FindMyPast. We may earn commissions from qualifying purchases – this does not affect the amount you pay for your purchase.

READ NOW

➤ Exploring the real Saint Patrick, insights from his own writings

➤ Leap year dances in Ireland 100 years ago

➤ The cuckoo in Irish folklore

➤ St Gobnait: patron saint of ironworkers, beekeepers and Ballyvourney

➤ Who was St Brigid – did she really exist?

A D V E R T I S E M E N T