Did a member of your family fall on hard times? Trace your ancestor’s story as we explore the surviving records for Ireland’s Poor Law Unions and their workhouses.

Even prior to the Great Irish Famine of 1845–52, the numbers of poor in Ireland had increased dramatically as a result of growth in population, their increasing reliance on the potato for sustenance, the division of land, a poor economy, the lack of waged work and the high rate of evictions, among other reasons. In Victorian Britain and Ireland, it was widely regarded among the elite that the poor, and particularly those that were able-bodied, were poor through their own fault.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

The workhouses

This period saw a shift towards incarcerating the poor in institutions, namely workhouses, away from “decent” society. The workhouses were designed through their physical structure and harsh regimes to punish the poor for their perceived idleness rather than to relieve suffering. The Irish Poor Relief Act came into effect in 1838 and consequently, Ireland was divided into 130 Poor Law Unions. A workhouse was built in each union and soon Ireland’s poor were being ushered behind the walls of these notorious institutions.

Between 1848 and 1850, 33 new Poor Law Unions were established and yet more workhouses were built. This workhouse system essentially replaced the traditional system of providing outdoor relief and almsgiving within the community.

The workhouses were designed by George Wilkinson and they followed a set layout: there was a small entrance block where the Board of Guardians and officers held meetings; the main block lay behind this and was usually a three-storey building containing the master’s office and several wards which had un-plastered walls, bare rafters, bare floors and straw mattresses; the block to the rear housed the kitchens, wash-houses, store rooms, bakery and often a hospital (infirmary); fever sheds were occasionally added later. Open fires were used for heating inside the workhouse but small windows were ineffective for ventilation, creating a smoky atmosphere. The buildings were often surrounded by a high stone boundary wall.

Paupers and inmates

The term “pauper” was applied to a recipient of Poor Law relief, while they were often known as “inmates” once resident in a workhouse. Before the Famine, ¾ of the population of Cork city were paupers. By 1847 Ireland’s workhouses were bursting at the seams with a nationwide average weekly number of 83,283 inmates. The numbers admitted were to further soar, with the weekly average number of inmates nationwide in 1851 standing in excess of 217,000.

In his tour of workhouses in the west of Ireland in 1850, Lord Sidney Godolphin Osborne observed that,

“The dirt and general filthiness of the yards, in which these barefooted, ill-clad children had to spend so many hours, made the whole affair more painfully offensive; dogs would have had more attention paid to them.”

>>> YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Life behind bars in Sligo Gaol

What do I need to know before I start?

Before beginning your search, try to find out the following:

- the name of your ancestor who spent time in a workhouse;

- when they were in the workhouse;

- the name of the workhouse or Poor Law Union.

Sign up to our newsletter

It is worth noting that in order to gain admission to the workhouse (typically) the whole family had to enter and destitution was a prerequisite. However, there are very many cases of parents abandoning their children at the workhouse.

Some would have lived substantial portions of their lives behind the high workhouse walls, while others may have been in and out of the workhouse on a regular basis, spending only short periods at a time inside.

Workhouse records

The full archival collection pertaining to a particular Poor Law Union and its workhouse could include indoor relief registers, admission and discharge registers, registers of births, deaths and marriages, inventories, punishment books, dietary books, the masters’ journals, minute books, medical registers, hospital records, vaccination registers, lunatic registers, outdoor relief registers, dispensary notices, account books, supplier contracts, receipts and correspondence (especially with the Poor Law Commissioners).

But the preservation of the records has been a rather haphazard process and the extent of preservation is variable from one union to the next. Unfortunately, much has been lost and many of the surviving collections are incomplete.

Where are the records kept?

Some are stored in central record repositories. For example, the records for the 28 Poor Law Unions in Northern Ireland are held in the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI) in Belfast; the records for the Dublin Unions are held in the National Archives and some of the records for Mayo have ended up in the National Library of Ireland. A large proportion of the records found their way to the local authorities, and are generally held in the archives or libraries run by the county council or city council in which the workhouse was located. Some records were simply retained in the workhouse, now often a hospital, or fell into private ownership.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

If you are wondering if the records for a particular workhouse have survived, it is worth checking the descriptive lists for the relevant archives, library or museum (these list all the collections in that specific repository). These lists are usually accessible online.

For example, detailed descriptive lists for the minute books for the meetings of the various Waterford Boards of Guardians can be accessed on the Waterford County Council website. Alternatively, you could contact the relevant repository directly and they will be able to assist. The records can be consulted usually by appointment only.

Below is an overview of some of the most useful records available, and will serve as a guide to researching your ancestor’s workhouse story.

- Admission and discharge registers

>

Unfortunately, very often admission and discharge registers have not survived or are missing. This is certainly the case for the Waterford workhouses. However, there are a small number of rare survivals scattered throughout Ireland.

The information contained in the registers varies enormously from union to union and over time but typically they include the inmate’s name, age, marital status, profession (if any), religion, previous address, state of health upon entering the workhouse, date of admission and date of discharge or death (if it occurred in the workhouse), as well as information regarding their next of kin. Some of these records pre-date civil registration, and so can help you break through a genealogical wall.

A small number of admission and discharge registers have been digitized and some are available on local authority websites.

>>> YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Digitized records for Stanwix Widows’ Almshouses in Thurles now online

For example, the admission and discharge registers for Shillelagh workhouse for the years 1842–1918 and for Rathdrum workhouse for the years 1842-1914 can be found on the Wicklow county council website. A number of admission and discharge registers for the workhouses in Thurles, Roscrea and Cashel have been digitized and are available on the Tipperary Studies website.

Workhouse admission and discharge registers can also be found on the subscription website Find My Past. This includes registers for the period 1840–1919 for three of the four Dublin workhouses (North Dublin Union, South Dublin Union and Rathdown Union), the registers for Sligo Union workhouse for the period 1848–59 and the registers for the Donegal workhouses (Unions of Ballyshannon, Donegal, Dunfanaghy, Glenties, Inishowen, Letterkenny, Milford and Stranorlar) for the period 1840–1922.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

It is worth noting that the North and South Dublin Unions frequently admitted paupers from across the country, not just those resident in Dublin, especially during the Famine. So no matter where your ancestor was from in Ireland, they could have been admitted to a workhouse in Dublin.

- Death and burial registers

>

Death was a common occurrence in the workhouses. In the winter of 1846–47, for instance, workhouse mortality reached 2,500 deaths per week nationwide. Some Poor Law Unions kept death registers recording the names of the deceased workhouse inmates, such as the 1848–50 death register for Cashel workhouse which is available to view on the Tipperary Studies website.

If the statistical books for a particular Poor Law Union have survived, these will probably record the number of deaths on a weekly basis but, unfortunately, will not include the names of the deceased. Clues about some deaths that occurred in the workhouse may also appear in contemporary newspapers, especially in the case of unusual deaths or during epidemics.

While initially some workhouse inmates were buried in the “ordinary” local cemetery, this was quickly abandoned in most Poor Law Unions in favour of separate cemeteries for inmates.

This was certainly the case in Clonakilty in West Cork where deceased inmates were brought “to a very distant and overcrowded graveyard” for the first couple of years before land was procured for a separate cemetery known as “Páircín a’ Chongair” (pictured below). This must surely relate to the sheer numbers dying in Clonakilty workhouse but also probably to a desire to again separate the workhouse inmates from “normal” society even in death.

>>> RELATED: The workhouse cemetery: “Clonakilty God help us”

In most cases, these designated cemeteries would have been consecrated by the chaplain of the workhouse.

In the early years of some workhouses, burials took place within the boundary walls of the workhouses (“intra-mural burials”), and often in the vicinity of the hospitals or fever wards. The remains of workhouse inmates at Manorhamilton (Co. Leitrim), Cashel (Co. Tipperary) and Kilkenny, for example, were uncovered in very close proximity to the workhouses and probably date to the 1840s/50s. Mass graves were not uncommon. In Kilkenny, for instance, excavations undertaken in 2006 identified the skeletons of approximately 970 individuals interred in 63 mass burial pits within the grounds of the workhouse.

In the vast majority of cases, the graves of workhouse inmates would not have been marked in any way, and so headstone inscriptions are not an avenue of research that can be explored. But some Poor Law Unions may have kept burial registers. These registers contain limited information, often no more than the date of burial, the name of the deceased and possibly the location of the grave. These records tend to be intermittent and patchy.

>>> YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Tracing your roots online using old records of Irish gravestone memorials and “Mems Dead”

If your ancestor was a member of the Church of Ireland (the Anglican church), it is possible that s/he would have been buried in the local church graveyard rather than the designated workhouse cemetery which was typically used predominantly for the burial of Catholic workhouse inmates. It should be noted that unlike their counterparts in the Roman Catholic Church, the majority of Anglican clergy tended to record burial details and so you may find your ancestor listed in the burial register for the cemetery used locally for burying Protestants.

- The minute books of the Boards of Guardians

>

The day-to-day management of each union and workhouse was the responsibility of a board of guardians, which included ex officio magistrates and others elected by ratepayers. The boards were answerable to the government-appointed Poor Law Commissioners, based in Dublin after 1847, and correspondence between the boards and the commissioners was regular.

The clerk of each union kept detailed minutes of the meetings of the board of guardians. In many instances the minute books have survived. These books are the best source of information on workhouses, containing invaluable details concerning the running of the workhouses, while also giving some insight into the lives of the destitute who resided within.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

The minute books usually contain information relating to the general business of the workhouses rather than individual inmates. However, individual inmates may have been named in the case of unusual circumstances, such as incidents relating to those who failed to keep the workhouse rules, who converted religion, who absconded, who were given help to emigrate or find employment or in the case of children who were boarded out.

The survival of the minute books is haphazard. For example, 75 books of minutes of the meetings of the Board of Guardians for the Clonakilty Poor Law Union, covering the years 1850–1924, are held in Cork City and County Archives on Great William O’Brien Street, Blackpool in Cork city. On the other hand, in the neighbouring Poor Law Union of Skibbereen the minute books unfortunately have been lost. This is particularly frustrating as Skibbereen is engrained in the Irish psyche as having suffered horrifically during the Famine and these records would no doubt have been illuminating.

Those who are researching the stories of individuals who spent time in the workhouses in Counties Wexford and Donegal are particularly fortunate as the minute books are available to view free of charge online. These original records are being released on a phased basis for Co. Wexford and currently you can view some of the minute books for the Unions of Enniscorthy, Gorey, New Ross and Wexford on the Wexford Archives website. Hopefully with further releases, we will have the opportunity to learn more about the riots (mainly involving women) that took place in New Ross workhouse in 1887 when the master and the paid vice-guardians were attacked.

The records for the Co. Donegal Unions of Ballyshannon, Donegal, Dunfanaghy, Glenties, Inishowen, Milford and Stranorlar are available on the Donegal County Council website but only for the years 1916 and 1917.

The Board of Guardian minute books for the Unions of Dublin, Galway, Donegal, Waterford, and four of the eight Co. Clare Unions – Ennistymon, Kilrush, Corofin and Ennis – are available on the subscription website Find My Past.

Extracts from the minute books from unions throughout Ireland have been transcribed and are available on various websites. In addition, the meetings of the Boards of Guardians were reported upon extensively in the newspapers of the time.

Civil records for workhouse inmates

From 1864 onwards there was a legal requirement to register the birth, death and marriage of every individual in Ireland; this obviously included every workhouse inmate. In most instances it would have been the duty of the master or matron of the workhouse to register these events with the local registrar for the district. This was in addition to their recording in the registers kept in the workhouse.

>>> RELATED: Irish civil records: what’s online and what’s not online?

Civil records are arranged by civil registration districts, which follow the same boundaries as the Poor Law Unions. Since it is not possible to search the civil records available online under townlands or parishes, it is important that you know within which “Civil Registration District/Office” the workhouse you’re interested in was located. A map of the registration districts is available online here.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

The General Register Office (GRO) for the Republic of Ireland holds all official records. The free website IrishGenealogy.ie provides access to the following civil registration records:

- Births index and original images: 1864–1924;

- Catholic marriages index and original images: 1864–1949;

- Non-Catholic marriages index and original images: 1845–1949;

- Deaths index: 1864–1974, original images: 1871–1974.

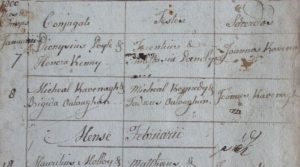

>

For those not available to view online, the original certificates can be ordered (for a fee) from the GRO. It is anticipated that more indexes will gradually be released online.

The official site of the Northern Ireland General Register Office (GRONI) allows access to the following:

- Birth records over 100 years old;

- Marriage records over 75 years old;

- Death records over 50 years old;

- Transcripts of records from 1922 onwards on a pay-per-view basis.

>

It is important to remember that in the past individuals, especially paupers, often did not know their date of birth or age, and so consequently, there may appear to be discrepancies between birth certs, baptism records and ages on census returns or death certificates.

The death certs of the workhouse inmates are perhaps the most revealing civil records. Along with the deceased’s name, marital status, occupation and age at death, brief details are provided regarding the cause of death. Reading between the lines, the death records can sometimes give you a glimpse of the conditions in the workhouse. Many deaths within the workhouse walls related to the spread of disease, while some resulted from poor diet, overworking, accidents or fights.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Church records for workhouse inmates

Church records include baptismal, marriage and less often burial registers. There is a great degree of variation in the level of detail contained within these records and there can be considerable variation even within a single parish or church. Transcriptions and original images of church records for some Roman Catholic, Church of Ireland and Presbyterian parishes are available on IrishGenealogy.ie and can be searched using your ancestor’s name or their parish. If you come up empty handed, there are a number of other ways to access these records.

>>> YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Our genealogical guide to navigating Northern Ireland’s church records

The original microfilm images of baptismal and marriage registers for over 1,000 Roman Catholic parishes, including the counties of Northern Ireland, can be viewed free of charge on the official website of the National Library of Ireland. The start date for a particular parish register varies enormously but is generally between the late 1700s and early 1800s, while the records available online conclude c.1880. The records on the NLI website are searchable by parish only and not by name. As such, it is necessary to know the name of your ancestor’s parish before commencing your search.

If your ancestor was born or wed post-1880, it is worth noting that most Catholic parishes hold their original records in local custody. Under these circumstances, we advise making contact directly with the relevant parish and they will be able to advise further.

Baptismal, marriage and burial records pertaining to members of the Church of Ireland community are housed in several different locations: some original registers are held in the National Archives, others in the Representative Church Body (RCB) Library and some are retained in the parishes. It is possible to visit the RCB Library and National Archives, both in Dublin, to conduct a search of these collections.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Records of Methodist births, marriages and burials which took place prior to about 1820 are also found in the Church of Ireland registers (for after this date, contact the local Methodist church). Unfortunately, a large volume of the Church of Ireland registers held in the Public Record Office was destroyed by fire in 1922 during the Irish Civil War.

If your ancestor was Presbyterian, their records are probably held in local custody or by the Presbyterian Historical Society. In Northern Ireland, PRONI holds many Presbyterian and Methodist records. Most records for Quakers are held in the Libraries of the Society of Friends in Dublin and Lisburn.

For workhouse inmates, some baptisms and marriages may have taken place within the dedicated workhouse chapel. However, in other instances, and especially in the case of those baptized in the Protestant faiths, the ceremonies took place in the local parish church.

>>> YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Understanding marriage settlements for Irish family history research

Census records for workhouses

If you had an ancestor in the workhouse in the early 20th century, they may have been present when the 1901 or 1911 census was carried out. There are few surviving census remains before 1901 and there are no censuses currently available for consultation after 1911.

Searching the online census records may help you determine whether your ancestor was in a workhouse at a certain date. The transcriptions of the 1901 and 1911 census returns can be searched for free and originals downloaded for free on the National Archives Census website. It is possible to search by name (“Search Census”) or by location (“Browse”). In the case of workhouse inmates, it is probably best to search by location because very often only the initials of the inmates – and not their full names – were recorded; this makes it a rather difficult task to try to track down a particular individual.

>>> YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: What can the census tell us about Ireland’s first president, Douglas Hyde?

The census forms that you need to pay particular attention to are Form E which is the “Return of Paupers in Workhouses” and Form I which is the “Return of Idiots and Lunatics in institutions” (the latter because workhouses very often had designated wards for people with disabilities or mental health conditions).

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

As well as their initials, the census return states their age, sex, religion, birthplace, occupation, marital status, years married, children born, children living, literacy, knowledge of the Irish language, specified illnesses, the number of years affected, the cause of the illness and if “Deaf and Dumb; Dumb only; Blind; Imbecile or Idiot; or Lunatic”.

Pictured above are a Form E return and a Form I return for the 1911 census. As you can see in this sample of occupants of Kilkenny workhouse all were Roman Catholics, many were illiterate unmarried servants from Kilkenny city or county, and a number had serious health conditions.

Emigration records for workhouse inmates

Emigration played a key role in the system of relief. Some workhouse inmates secured passage to America or Australia from family members, sometimes aided by the union. For instance, in Milford (Donegal) the Board of Guardians was requested to sanction the expenditure of £3 from the rates of Termon electoral division to pay the balance of the cost of passage to Philadelphia for a six-year-old named Catherine Murray. Her parents, who were already residing in Philadelphia, could only afford to pay £2 7s towards her passage.

Assisted (or forced) emigration also became a feature of some workhouses. Women and orphan girls in particular were favoured. By the 1840s, the colonial authorities in Australia wanted to recruit female settlers because of the gender imbalance, with the ratio standing at eight or nine males to every female. The Australian authorities funded the transportation of females emigrating from Ireland to Australia but demanded that the girls be in good health, preferably aged between 14 and 18, have industrial skills and “be imbued with religion and morally pure”. The scheme was called the Earl Grey Famine Orphan Scheme after its proponent Henry Grey, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies.

In Australia it was hoped that the girls would work, marry, have children and help colonize the continent. The scheme had the added bonus that it would reduce numbers in the fiercely overcrowded workhouses. Through this scheme between 1848 and 1850, over 4,000 females were sent to Australia, including 137 girls from the Mayo workhouses and 110 from Skibbereen workhouse alone.

We mentioned earlier that the minute books for the Wexford workhouses are available online. These contain information pertaining to the Earl Grey emigration scheme (1848–50). In the Gorey minute books, for example, the prospective female emigrant’s name, age and qualifications – their ability to read, write, spell, knit, sew and wash – are recorded, as well as the length of time that each girl had been an inmate in the workhouse; this is particularly valuable given that the admission and discharge registers for this union have not survived.

More emigration schemes followed that sent workhouse inmates to locations other than Australia. Between 1851 and 1870, some 27,425 workhouse inmates were assisted to emigrate, with hundreds sent from the workhouses in Kerry and Clare in 1851 alone.

Sign up to our newsletter

Tracing their emigration can be a difficult task but some passenger ship lists are available online on genealogy websites, though many of the records are only viewable via paid subscription.

Information about emigrants was usually gathered at the port of destination rather than the place of departure. Pre-1923 immigration records for Australia are held in relevant state archives and libraries. From 1855–90, Castle Garden was the official immigration centre in the United States at the Port of New York, while Ellis Island opened in 1892 and continued in use until 1924. The Castle Garden website has a free online searchable database of 11 million immigrants and the Ellis Island website has a free online searchable database of over 22 million arrivals. Information about records for emigrants to Canada from 1865 onwards is available in the Library and Archives Canada website.

Census records in the destination country may also prove useful, as well as naturalization records.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

County homes and county hospitals

After the 1850s the numbers entering workhouses diminished significantly. In 1872 the Irish Poor Law Commission was abolished and its duties were given to the newly formed Local Government Board for Ireland. Eventually, many workhouses came under the management of religious orders, such as the Sisters of Mercy.

The workhouses closed in the early 1920s and most of the buildings came under the County Schemes which grouped all the former Poor Law Unions in each county into districts, with each district administered by a board of health or a board of public assistance. Many of the workhouses became county homes and county hospitals, and very often the workhouse inmates remained within their walls. Unfortunately, the conditions in many of these institutions remained primitive for decades after and the lives of many of those who remained improved little.

Advertising Disclaimer: Irish Heritage News is an affiliate of FindMyPast and the British Newspaper Archive – we earn commissions from qualifying purchases.

Sign up to our newsletter

Subscribe to the Irish Heritage News newsletter and follow us on Facebook, X and Instagram for all the latest heritage stories.

READ NOW

➤ Irish genealogy news round-up, June 2025

➤ Tracing your roots online using old records of Irish gravestone memorials and “Mems Dead”

➤ The workhouse cemetery: “Clonakilty God help us”

➤ A guide to navigating Northern Ireland’s church records

➤ Find your ancestors in Ireland’s historical school records

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Crossman, V. 2003. ‘The New Ross workhouse riot of 1887: Nationalism, class and the Irish Poor Laws’. Past and Present 179, pp.135-58.

Donegal County Archives, Milford Board of Guardians, DCA/BG/119/1/6, 26 Jun. 1854.

Geber, J. 2012. ‘Burying the Famine dead: Kilkenny Union workhouse’. In J. Crowley, W.J. Smyth and M. Murphy (eds) Atlas of the Great Irish Famine, 1845–52. Cork, pp.341-48.

Higginbotham, P. The Workhouse: the story of an institution.

[https://www.workhouses.org.uk/]

Kearney, T. ‘Irish Famine orphan story’.

[https://skibbheritage.com/irish-famine-orphan-story/]

Keneally, T. 2012. ‘The Famine and Australia’. In J. Crowley, W.J. Smyth and M. Murphy (eds) Atlas of the Great Irish Famine, 1845–52. Cork, pp.550-60.

Lynch, L.G. 2014. ‘An Assessment of Health in Post-medieval Ireland: ‘One vast Lazar house filled with famine, disease and death’’. Unpublished PhD thesis, University College Cork.

[https://cora.ucc.ie/bitstream/

handle/10468/

1417/LynchLG_PhD2014.pdf?sequence=2]

Mitchell, S. ‘The female orphan scheme to Australia in the 1840s’.

[https://womensmuseumofireland.ie/

articles/the-female-orphan-scheme-to-australia-in-the-1840s]

O’Connor, J. 1995. The Workhouses of Ireland: The fate of Ireland’s poor. Dublin.

O’Leary, M. 2017. ‘The origins of Clonakilty Poor Law Union and workhouse, 1850–52’. Clonakilty Historical & Archaeological Journal 2, pp.149-77.

O’Leary, M. 2021. ‘’Clonakilty God help us’: the early years of the workhouse, 1852–56’. Clonakilty Historical & Archaeological Journal 3, pp.281-323.

Osborne, S. G. 1850. Gleanings in the West of Ireland. T. & W. Boone.

3 Responses

Thankyou for this great insight of the workhouses and how they worked. I am a descendant of one of those Earl Grey Orphans, that came to Australia in 1848. Since reading this I would love to find out where my MaryAnn Early came from, was she and her sister’s in a workhouse?. On the ships records (the Lady Kennaway 1848) it stated that she came from Sligo R/C couldn’t read or write and that she had a mother. MaryAnn was with her two sister’s Elizabeth and Ann . On death certificates of MaryAnn and Ann they both have different father’s ….. John Boyle and Michael Early, Roscommon was mentioned on one certificate as place of birth. As yet we haven’t found Elizabeth’s place of death.

The 3 sister’s did there bit for populating the new colony…. Elizabeth had 7 children, MaryAnn had 12 and Ann had 5.

If anyone could help me find out anymore information on these 3 resilient beautiful women I would be forever grateful. Thank you

Hi there, interesting!! Elizabeth Early born 1851, Kilanummery, Co Leitrim. Daughter of Thomas Early 1830-1875, Kilanummery.

I am also a descendant of one of the Irish Famine Orphans to Australia. Her name was Mary Therese Taaffe. Also her younger sister Eliza came to Australia on the Inconstant with Mary. Mary was 16, Eliza 14. They came from North Dublin Workhouse and arrived here in 1849. Mary went on to marry Samuel Knowles (aka Dunn) in Adelaide, who was an absconder from Tasmania penal colony. They had 14 children on the Victorian goldfields.