We explore the documentary, archaeological and folkloric evidence relating to the Irish early medieval female saint Gobnait and take a close look at the popular pilgrimage dedicated to her in Ballyvourney.

St Gobnait

Believed to have lived in the 6th century, St Gobnait is the patroness of Ballyvourney in Co. Cork. This early Irish female saint is still revered today, not just in Ballyvourney but at many other church sites and holy wells in Munster. Her feastday is typically celebrated on 11 February, during which patterns are still held in her honour.

The term “pattern” (deriving from “patron”) refers to rituals of devotion, usually comprising pilgrimage rounds and stations, made annually to the patron of a church or holy well.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

St Gobnait in the early sources

Early recorded information on the saint is relatively scarce. Unfortunately, there is no known Life of St Gobnait. A saint’s “Life” is essentially a biography written after the saint’s death and is usually the principal source of evidence for a saint’s existence and life story.

St Gobnait is, however, mentioned in the Life of St Abbán, a male saint who was also linked with Ballyvourney. Two versions of this Life survive – a Latin Life (Vita Sancti Abbani) of probable 12th or 13th-century date and an abbreviated Irish Life (Betha Abáin) of later date. Both versions probably draw from earlier sources that have not survived.

Sign up to our newsletter

Referring to Ballyvourney by its old names “Huisneach” and “Boirneach”, these texts tell us that:

“In the territory of Muscraige, Abbán built a monastery called ‘Huisneach’ [Ballyvourney]. Abbán then surrendered this place and monastery to the virgin St Gobnait.” (Translation by Dr Ellen Ganly)

Despite the absence of her own hagiographical account, St Gobnait is referred to in several other medieval texts, including the 8th or 9th-century Martyrology of Tallaght, the 12th-century Book of Leinster and the 12th-century Martyrology of Gorman. According to the foremost expert on Irish saints, Dr Pádraig Ó Riain, the genealogies trace Gobnait’s ancestry to the Munster dynasty of the Múscraighe Midíne.

St Gobnait’s journey

Regardless of the meagre documentary evidence, Gobnait plays a prominent role in local lore in the parish of Ballyvourney, where she is still venerated with the utmost devotion, as well as in other early sites linked with the saint. Much of the story of St Gobnait has been handed down to us through oral folklore and placename evidence.

From the oral tradition, we learn that Gobnait either originated from or travelled to the island of Inis Oírr – the smallest of the Aran Islands. There, you’ll find the ruins of a small pre-Romanesque church called Kilgobnet (Cill Ghobnait) meaning Gobnait’s Church.

Please help support

Irish Heritage News

A small independent start-up in West Cork

Give as little as €2

Thank You

On Inis Oírr, an angel appeared to Gobnait and instructed her that she would see nine white deer grazing at the “port a h-aiséirí” or “place of her resurrection”. Setting off from the island, she moved down the country and left her mark on numerous places throughout Munster, which often preserve her name or alternative appellations and anglicizations of her name in the form of Deborah, Derivla, Abigail and Abby.

>>> RELATED: Who was the Ballyvourney thief, an Gadaidhe Dubh?

For example, in Co. Kerry, there are two early ecclesiastical sites named Kilgobnet, one on the Dingle Peninsula near Dún Chaoin and the other near the village of Kilgobnet not far from Killorglin. Both boast a variety of interesting monuments, including a holy well called Tobar Ghobnait (meaning Gobnait’s Well) on the Dingle Peninsula, while at the other site, a circular cell-like stone structure and a nearby ringfort were recorded as “St Gobnet’s cloghaun” and “Lissgubnet” respectively. At both sites, a pattern was traditionally held on the saint’s feastday, 11 February; however, only on the Dingle Peninsula are rounds of the various monuments still performed on this date.

A F F I L I A T E A D

Near Ballyagran in Co. Limerick, the antiquarian TJ Westropp recorded a church called Kilgobnet in c.1904, while close by is a ringfort named St Gobnet’s Fort and a holy well known variously as St Gobnait’s Well, St Derivla’s Well and St Deborah’s Well. In 1955, Caoimhín Ó Danachair noted the belief that “Saint Gobnait lived here” and “a white stag is sometimes seen at the well”. A fair was held here on 11 February into the late 1800s, while rounds of the well were still carried out up until the mid-1950s.

Also in Limerick, near Killmallock and probably associated with Cloheen graveyard and probable early church site, is another holy well dedicated to the saint called Tubbergubbanit but more often recorded as Deborah’s Well.

>>> RELATED: Cloheen graveyard, Co. Limerick: evidence of its medieval past

Further east in Co. Waterford, in the parish of Kilgobnet, you’ll find a medieval church dedicated to the saint, as well as a holy well previously called Tobergobnet. Again, in the past, a pattern was held at the well on 11 February.

Eventually, Gobnait found her way to West Muskerry in Co. Cork. The saint is said to have seen three white deer near Clondrohid, six in the townland of Killeen, before finally finding nine white deer, as foretold by the angel, at Gortnatubbrid in Ballyvourney. There, Abbán surrendered his monastic foundation to St Gobnait and there she remained for the rest of her life.

These are just some of the places traditionally associated with this early medieval saint. Amanda Clarke of Holy Wells of Cork and Kerry charts the potential route taken by St Gobnait and provides details of the various stopping points in a series of blog posts (starting here).

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

St Gobnait’s cult at Ballyvourney

St Gobnait’s churches

A short distance south of the village of Ballyvourney is an early medieval ecclesiastical site featuring two churches dedicated to St Gobnait – a late medieval parish church (Teampall Ghobnatan) and a 19th-century Church of Ireland building – surrounded by an enclosed graveyard (Reilg Ghobnatan). This church site is traditionally believed to be the site of St Gobnait’s foundation.

St Gobnait’s grave

Perhaps the most important site at Ballyvourney is the grave of the founding saint. Sited within the graveyard, a low grass-covered stone mound is believed to mark St Gobnait’s final resting place. The mound is surmounted by two flat slabs roughly carved with crosses and a piece of a bullaun stone, with another part of a bullaun nearby. At the base of the mound is a flat slab with two depressions, which pilgrims use as a kneeler.

St Gobnait’s house

Across the road from the graveyard is a stone-built circular hut structure measuring approximately 10m (30ft) in diameter. Tradition has it that the saint lived in this hut and so it is called St Gobnait’s House or St Gobnait’s Kitchen.

It was excavated in 1951 by MJ O’Kelly, Professor of Archaeology at University College Cork. Excavation revealed a large post-hole in the centre of the house, which probably supported the roof and two posts for the door frame. Beneath the circular structure was a wooden rectangular house(/s) possibly dating to the 9th or 10th centuries AD.

The excavation also revealed numerous iron-smelting and metal-working pits, furnace bottoms, tuyere fragments, crucibles and large amounts of charcoal and slag (the waste product of iron smelting). In relation to the extensive evidence for ironworking at Ballyvourney, it is interesting to note that Gobnait is the patron saint of ironworkers. The name Gobnait combines the pet name Gobba, which derives from “gobha” or “gabha” meaning “smith”, and the feminine suffix -nait/-naid.

Other artefacts found during the excavation – including a glass bead, a spindle whorl, knives, nails and stone objects such as flints, whetstones and quern stones – were interpreted as evidence of occupation during the first millennium AD. However, as radiocarbon dating had only been recently discovered, O’Kelly could not pin down the period of occupation more precisely.

A F F I L I A T E A D

Following the excavation, the circular hut was conserved and modern limestone columns were erected to mark the positions of the central post-hole and the post-holes that supported the door.

St Gobnait’s wells

Close to St Gobnait’s House, the excavation team uncovered a well that O’Kelly believed was used for domestic purposes connected with the hut site. After the excavation, the well was reconstructed and has since been venerated.

A holy well, traditionally called Tobar Ghobnatan, is located about 50m southeast of the cemetery.

St Gobnait’s medieval wooden statue

Significantly, a 13th or 14th-century wooden statue of the saint is kept in Ballyvourney. A rare survival, it is one of only five extant medieval wooden statues of Irish saints.

Made of oak, it is 69cm (27in) tall. Its back is hollowed out, which is a feature of medieval wooden statues of this form and date. The face is now featureless apart from the left eye. Her left arm is folded across her chest and her right hand is by her side, holding a fold of her dress. Her clothes still show some remnants of paint. Previous descriptions indicate she is wearing a red dress, white wimple and blue cloak.

The wooden statue of St Gobnait is now stored in the Catholic parish church in the village and is only placed on display twice a year: 11 February (St Gobnait’s feastday) and Whitsunday. Tradition has it that this statue replaced an earlier gold statue of St Gobnait, which was buried in a place known as “Clais na hIomhaighe” (“Pit of the Image”).

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

St Gobnait’s modern stone statue

Across the road from the graveyard and close to the excavated well stands a striking life-sized limestone statue of St Gobnait, carved by renowned Cork sculptor Séamus Murphy. It was unveiled on Whitsunday 1951, shortly before O’Kelly’s excavation began.

At the base of the statue, carvings of bees are the dominant motif in reference to St Gobnait’s patronage of beekeepers. The saint herself is reputed to have kept bees for their honey, which was an extremely important food source, with medicinal properties, at a period when sugar was unknown in Ireland.

One legend tells us that Gobnait sent a swarm of bees after raiders, who had attempted to steal cattle in Ballyvourney. Interestingly, St Gobnait is also known as Deborah and that name derives from the Hebrew word for bee.

Past devotion to St Gobnait at Ballyvourney

The two annual “pattern” days at Ballyvourney are the saint’s feastday (11 February) and Whitsunday. Pilgrimages in the saint’s honour probably commenced in the medieval period and Gobnait’s cult was certainly flourishing in Ballyvourney by 1601 when Pope Clement VIII granted a special indulgence of

“ten years and quarantines to the faithful who would visit the parish church of Gobnet on her feast-day, would confess and receive holy Communion and would pray for peace among Christian princes, for the expulsion of heresy and for the exaltation of Holy Mother Church.”

Two years later, on 1 January 1603, O’Sullivan Beare, along with his soldiers and followers, during their arduous journey from Beara to Breifne, on reaching

“the populous village of Ballyvourney, dedicated to Saint Gobnata … paid such vows as each one list, gave vent to unaccustomed prayers, and made offerings, beseeching the saint for a happy journey.”

Sign up to our newsletter

Sir Richard Cox described Ballyvourney in 1687 as

“a small village, considerable only for some holy relick (I think of St. Gobonett) which does many cures and other miracles, and therefore there is great resort of pilgrims thither.”

The relic referred to here is likely a reference to the medieval wooden statue of St Gobnait. In 1727, Protestant clergyman John Richardson wrote disparagingly of local belief in the power of this statue, declaring it “rank idolatory” (sic.). He gave the following account of the rituals involving the statue:

“It is set up for their Adoration, on the old ruinous Walls of the Church. They go round the Image thrice on their Knees, saying a certain number of Paters, Ave’s and Credo’s. Then they say the following Prayer in Irish, A Gubinet tabhair slán aon Mbliathan shin, agas Sábhál shin o gach Geine & sórd Egruas, go specialta on Bholgagh; that is O Gubinet, keep us safe from all kinds and sorts of Sickness, especially from the Small Pox. And they conclude with kissing the Idol, and making an Offering to it, every one according to their Ability, which generally amounts in the whole to Five or Six Pounds.”

Richardson noted that the statue was in the custody of the local O’Herlihy family. Traditionally, they were the hereditary stewards (“airchinnigh”) of St Gobnait’s graveyard and the keepers of the statue. They would lend it to people who were ill, especially those inflicted with smallpox.

>>> READ MORE: St Brigid’s Day customs and traditions in Co. Kildare in the 1930s

Richardson’s writings regarding local beliefs and customs are filled with anti-Catholic rhetoric:

“when anyone is sick of the Small Pox, they send for it [the statue], sacrifice a Sheep to it, and wrap the skin about the sick person, and the family eat the Sheep. But this Idol hath now much lost its Reputation, because two of the O Herlehy’s died lately of the Small-Pox.”

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

This wooden statue of St Gobnait was also mentioned by Charles Smith in his history of Cork in 1750. It was then “kept in a chest very private, and never exposed but upon festival days, and when it is carried to sick people”. Regarding the feastdays, Smith remarked that on those days, the statue was displayed in the graveyard on a small stone cross; there, pilgrims would encircle the statue on their knees while reciting prayers.

He also referred to a custom performed by pilgrims of tying handkerchiefs about the neck of the statue, “which they imagine will preserve them from several diseases”. Daphne Pochin Mould described a similar scenario in the 1950s, stating that “one lays the ribbon lengthwise, then around the neck and round the waist, and gives a final rub along the whole statue with it”. Traditionally, the statue was also used during oath-swearing rituals.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the saint’s feastday and Whitsunday attracted enormous crowds and accounts of boisterous activities on these days are numerous. For example, there are reports of faction fights between two long-feuding local families, the Lynchs and the Twomeys. Begging was also so common in Ballyvourney on these days that bacachs (beggars) earned the nickname “Cléire Gobnaiti” (“Gobnait’s Clergy”).

>>> YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Say it in Irish: beggar – bacach

Pilgrimage at Ballyvourney today

Although the pilgrimage rounds forming the Turas Ghobnatan have been adapted over time, they are still very much part and parcel of life in Ballyvourney. The most popular days to undertake the rounds are still St Gobnait’s feastday and Whitsunday but they can be performed at any time as a mark of devotion to the saint or to seek a cure for a sick relative or friend.

An ulaidh uachtarach (the upper station)

Today, St Gobnait’s House and the modern statue are grouped together as part of the first station. The rounds start at the statue with the following prayer in Irish:

“Go mbeannaí Dia dhuit, a Ghobnait Naofa,

Go mbeannaí Muire dhuit agus beannaím féin duit,

Is chugat-sa a thánag ag gearán mo scéil leat,

Is ag d’iarraigh leigheas ar son Dé ort.”(“May God bless you, O Holy Gobnait,

May Mary bless you and I bless you myself,

To you I come complaining of my situation,

And asking you, for God’s sake, to grant me a cure.”)

Twice the pilgrim walks around St Gobnait’s House and the statue making a large circle. Then, the pilgrim makes a smaller circle around St Gobnait’s House only. Each time a round (i.e. a circle) is made, the pilgrim recites seven Our Fathers, seven Hail Marys, seven Glorias and the Apostle’s Creed. The rounds are always walked slowly ar deiseal (in a clockwise direction).

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

As part of the ritual activities at the first station, pilgrims, using small stones, often carve crosses into the modern limestone columns that mark the position of the post-holes at St Gobnait’s House. The reconstructed well excavated in the 1950s is also visited by some pilgrims, as part of this station, who take a drink of its water.

An ulaidh láir (the middle station)

After this, the pilgrim continues to a number of stations within the graveyard, always walking in a clockwise direction and reciting the same prayers at each station (seven Our Fathers, Hail Marys and Glorias). The first of these stations is St Gobnait’s Grave. Pilgrims often leave behind votive offerings at the grave-site, such as rosary beads, holy statues, pieces of cloth and even mobile phones.

An tríú ulaidh (the third station)

Then, it’s on to the medieval church, which is circled four times (each time it is rounded, a decade of the Rosary is recited), stopping at the site of the ruined clogás (bell-tower), before entering the old church on the southern side.

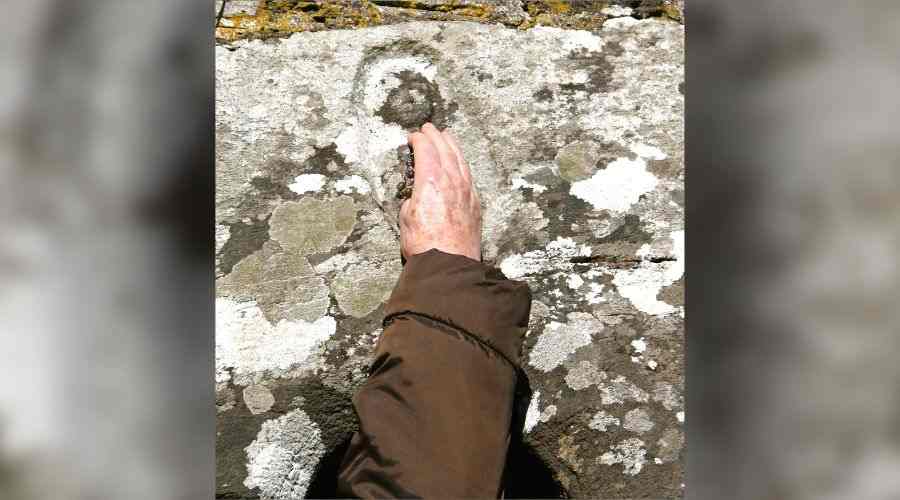

After reciting the usual set of prayers once again (seven Our Fathers, Hail Marys and Glorias), the devotee then goes to a window in the south wall of the church, where on the exterior there is an unusual carving portraying the torso, head and arms of a human figure.

Locally, it is believed to represent St Gobnait, but some archaeologists have interpreted it as a sheela-na-gig. Here, the pilgrim, stretching their arm out the window, makes the sign of the cross on the carved figure with rosary beads or a ribbon, and then makes the sign of the cross three times on their own forehead.

On leaving the church, the pilgrim again circles the church and then stops at the southeastern corner where the tomb of the 17th-century priest Fr O’Herlihy is located. In the past, the priest’s thigh bone was rubbed on ailing body parts in the belief that it would bring about a cure. As usual, seven Our Fathers, Hail Marys and Glorias are recited at this stopping point.

The pilgrim then proceeds to the bulla, a spherical agate stone mysteriously lodged in the western gable of the church. The pilgrim makes the sign of the cross on the bulla and three times on themselves. The usual prayers are then recited. The bulla, very much associated with St Gobnait in her role as protector of Ballyvourney, has a long tradition of miraculously curing both humans and animals. The pilgrim rubs a ribbon or a handkerchief on the bulla, which is believed to have accrued the power to cure illnesses from the stone.

The final station

The final station of the pilgrimage is the holy well, Tobar Ghobnatan, a short walk from the graveyard. While walking along the road to the well, a decade of the Rosary is said (the fifth and final decade). After the usual seven Our Fathers, Hail Marys and Glorias are recited at the holy well, the pilgrim takes a drink from the well, which is believed to have healing powers.

The round typically finishes with one of the following two prayers being recited in Irish:

“Ar impí an Tiarna agus Naomh Ghobnatan mo chuid tinnis d’fhágaint anseo.”

(“Imploring the Lord and St Gobnait to relieve me of my sickness.”)

or

“A Ghobnait an dúchais

Do bhíodh I mBaile Mhuirne

Go dtaga tú chugamsa

Le d ’chabhair is le d’ chúnamh.”

(“O Gobnait of Ballyvourney, come to me with your help and your assistance.”)

Beside this holy well is a rag tree. Many offerings have been left behind at the well and on the tree, such as rosary beads, holy statues and pieces of cloth. By leaving behind these objects, pilgrims believe they are casting off their illnesses.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

The wooden statue

In c.1843, the Catholic parish priest in Ballyvourney assumed responsibility for the medieval wooden statue; even today, it remains locked away in the sacristy of the church for much of the year. However, if you happen to visit Ballyvourney on the saint’s feastday or Whitsunday, you will have the opportunity to view the statue in the Catholic church.

The customs associated with the statue have changed little in recent centuries. On the two annual pilgrimage days, devotees, following the old tradition, use ribbons to “measure” the statue lengthwise and around the waist and feet. These ribbons are known as “tomhas Ghobnatan” (“Gobnait’s measure”) and are believed to have curative properties. John Richardson, who claimed that the statue’s reputation was in doubt in the 18th century, would surely be surprised to find that it is still venerated to this day.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

If you have visited Ballyvourney or any other sites associated with St Gobnait, we’d love to hear from you in the comment section below. For those of you who have not visited Ballyvourney, you can take a virtual tour here.

Advertising Disclaimer: This article contains affiliate links. Irish Heritage News is an affiliate of FindMyPast. We may earn commissions from qualifying purchases – this does not affect the amount you pay for your purchase.

READ NOW

➤ Who was the Ballyvourney thief, an Gadaidhe Dubh?

➤ Who was Saint Brigid – did she really exist?

➤ How the relics of St Valentine ended up in Dublin

➤ Exploring the real Saint Patrick, insights from his own writings

➤ The Ballingeary Gaeltacht roots of Los Angeles’ Cardinal Timothy Manning

Archaeological Survey of Ireland, RMPs CO058-013001; CO058-034001; CO058-034003; CO058-034004; CO058-034005; CO058-034006; CO058-034007; CO058-034008; CO058-034009; CO058-034011; CO059-065003; CO070-039001; GA120-002001; KE052-003001; KE052-005; KE052-007; KE065-040; KE065-042001; LI038-150; LI040-110; LI041-071; LI046-009; LI046-012; WA031-001001; WA031-001003.

[https://maps.archaeology.ie

/HistoricEnvironment]

Chaomhánach, E. ‘The bee, its keeper and produce, in Irish and other folk traditions’.

[https://ia.eferrit.com/

ea/64d0dea0a812115d.pdf]

Clarke, A. ‘Three wells dedicated to St Gobnait, Baile Mhúirne’. Holy Wells of Cork and Kerry, 12 Feb. 2016.

[https://holywellscorkandkerry.com/

2016/02/12/

three-wells-dedicated-to-st-gobnait-ballyvourney/]

Clarke, A. ‘Thinking out Gobnait’. Holy Wells of Cork and Kerry, 23 Jun. 2019.

[https://holywellscorkandkerry.com/

2019/06/23/

thinking-out-gobnait/]

Clarke, A. ‘A peregrination part 1: the wanderings of St Gobnait’. Holy Wells of Cork and Kerry, 20 Feb. 2021.

[https://holywellscorkandkerry.com/

2021/02/20/

a-peregrination-the-wanderings-of-st-gobnait-1/]

Clarke, A. ‘A peregrination part 2: meet the family’. Holy Wells of Cork and Kerry, 28 Feb. 2021.

[https://holywellscorkandkerry.com/

2021/02/28/

a-peregrination-part-2-meet-the-family/]

Clarke, A. ‘A peregrination part 3: the home run’. Holy Wells of Cork and Kerry, 7 Mar. 2021. [https://holywellscorkandkerry.com/

2021/03/07/

a-peregrination-part-3-the-home-run/]

Clarke, A. ‘St Gobnait: she’s a fine woman’. Holy Wells of Cork and Kerry, 14 Mar. 2021. [https://holywellscorkandkerry.com/

2021/03/14/

st-gobnait-shes-a-fine-woman/]

Clarke, A. ‘Still in pursuit of St Gobnait’. Holy Wells of Cork and Kerry, 16 Jan. 2022. [https://holywellscorkandkerry.com/

2022/01/16/

still-in-pursuit-of-st-gobnait/]

Ganly, E. 2020. ‘The Life and Cult of St. Abbán: a dossier study’. PhD thesis, Maynooth University.

[https://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/

14872/1/Ellen%20Ganly-%20PhD%20

Thesis%20%28For%20

Exams%20Office%29.pdf]

Harbison, P. 1992. Pilgrimage in Ireland: the monuments and the people. Syracuse University Press: Syracuse.

Harris, D.C. 1938. ‘Saint Gobnet, abbess of Ballyvourney’. Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Seventh Series 8.2, pp.272-77.

Harris, D.C. 1939. ‘Saint Gobnet, abbess of Ballyvourney’. Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, Seventh Series 9.3, pp.177-78.

Herstoric Ireland. ‘Pilgrimage to St Gobnait of Ballyvourney’, 2 Dec. 2019.

[https://www.herstoricireland.com/

blog/pilgrimage-to-st-gobnait-of-ballyvourney]

Hurley, Fr. 1945–50. Fr. Hurley’s Notes. Unpublished historical and folkloric notes made by former parish priest of Ballyvourney deposited in Ballyvourney Library.

Kelly, M.T. 1897. ‘Saint Gobnata, and her hive of bees’. Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society 3.27, pp.100-06.

Lewis, S. 1837. A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland vol.1. S. Lewis & Co.: London, p.169.

Lynch, M.M. 2010. ‘The archaeology and folklore of pilgrimage in Ballyvourney’. Unpublished diploma dissertation in local & regional studies, UCC.

MacLeod, C. 1946. ‘Some mediaeval wooden figure sculptures in Ireland: statues of Irish saints’. Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 76.4, pp.155-70.

Nugent, L. 2020. Journeys of Faith: stories of pilgrimage from medieval Ireland. Columba Books: Dublin.

Ó Cuiv, B. 1990. ‘Béaltraidisiún Chorcaí: a chúlra’. Béaloideas 58, pp.181-202.

Ó Danachair, C. 1955. ‘The holy wells of Co. Limerick’. Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 85.2, pp.193-217.

Ó Danachair, C. 1960. ‘The holy wells of Corkaguiney, Co. Kerry’. Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 90.1, pp.67-78.

Ó hÉaluighthe, D. 1952. ‘St Gobnet of Ballyvourney’. Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society 185, pp.43-61.

O’Kelly, M.J. 1952. ‘St Gobnet’s House, Ballyvourney, Co. Cork’. Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society 185, pp.18-40.

Ó Riain, P. 2011. A Dictionary of Irish Saints. Four Courts Press: Dublin.

O’Sullivan Beare, P. pre-1621. Chapters towards the History of Ireland in the Reign of Elizabeth.

[https://celt.ucc.ie//

published/T100060/index.html]

Schools’ Collection, vol. 342, pp.135-42. National Folklore Collection, UCD.

Smith, C. 1750 (republ. 1893). The Ancient and Present State of the County and City of Cork. Guy and Co.: Cork.