Between 1746 and 1752, Edward Synge, Bishop of Elphin, sent 221 letters to his only surviving child, Alicia, then a young teenager. The letters reveal great banter between the pair, while also offering a unique peek into the everyday lives of the upper echelons of mid-18th-century Anglo-Irish society.

Who was Edward Synge?

Born in Cork in 1691, Edward Synge came from a long line of influential Anglican clergymen. He was the eldest son of Edward Synge, Archbishop of Tuam, from Innishannon and the grandson of Englishman Edward Synge, who rose to the position of bishop of Cork, Cloyne and Ross. His granduncle and brother were also bishops, while other family members held various important clerical positions. They were also related to the famous Irish playwright John Millington Synge (1871–1909), author of The Playboy of the Western World.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Educated in Cork by the Scotsman Mr Mulloy and then in Trinity College Dublin, Synge’s first appointment was the living of St Audoen’s church, Dublin, in 1719. After several subsequent appointments, he was consecrated bishop of Clonfert in 1730. Translated to Cloyne a year later and to the Diocese of Ferns and Leighlin two years after that, before he was finally appointed bishop of Elphin in 1740, where he remained until his death in 1762. He became known as “Edward Elphin” to distinguish him from all the other Edwards in the Synge family.

A towering figure, Synge was over 6ft tall, of independent mind and something of a philosopher. He was a critic of the penal laws, which he believed were damaging to society. In their place, he argued for a limited form of tolerance and liberty of conscience. But he strongly advocated for conversion and encouraged proselytization through education and charity schools for Roman Catholic children. Always politically active, he backed Henry Boyle, 1st Earl of Shannon, as the speaker of the Irish House of Commons; the latter went on to play an important role in Irish politics for almost 50 years.

Sign up to our newsletter

The Synge family

In 1720, Edward Synge married Jane Curtis from Roscrea, Co. Tipperary. The couple had seven children: Edward, Sara, Jane, Catherine, Mary, Robert and Alicia. The family lived in a large house on Kevin Street in Dublin. They were very wealthy and life in the capital kept them busy.

Sadly, most of the Synge children died in infancy or in their youth, though Edward died at age 18 and Robert lived until he was about 21, while Alicia was the only one to survive into old age. Synge was dealt another massive blow with the untimely passing of his wife in 1737 after a two-day illness.

Edward Synge’s letters to Alicia

To meet his pastoral duties, the widowed bishop spent the summers in his diocese in Elphin, Co. Roscommon, while his only surviving child, Alicia, remained in the city with her governess and companion Blandine Jourdan (a member of the Huguenot community and granddaughter of the first librarian of Marsh’s Library).

>>> YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Letters from 1812 written by noted botanist Ellen Hutchins explored in new podcast

It is through Edward Synge’s 221 letters to his adolescent daughter that he is best known. These were written in the summers of 1746 through 1752. The letters were kindly gifted to the Library of Trinity College Dublin by the late historian Dr Marie-Louise Legg (1933–2015), a descendant of Edward and Alicia Synge. Legg transcribed and published the large collection of letters in her book The Synge Letters: Bishop Edward Synge to His Daughter Alicia, Roscommon to Dublin, 1746-52, which is available to purchase on Amazon.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

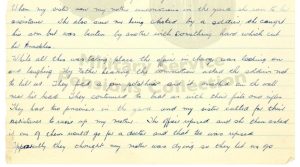

Unfortunately, Alicia’s letters have not survived. Still, her father’s voice charts her journey to womanhood while also offering a peek into the everyday lives of the upper echelons of mid-18th-century Anglo-Irish society.

The letters reveal great banter between the pair and are littered with the many good-humoured pet names he applied to his daughter, such as “My Dear Giddy Brat”, “Miss Sly-boots”, “Mrs Giddy-boots”, “Mrs Bold-face”, “my little Bee”, “my poor Mumper”, “sawcy Madam” and “Huzzy”. Forever teasing her, he frequently refers to her “prattle”:

“Your prattle either with tongue or with pen, will always be pleasing to me”.

“My Dear Girl’s long letters are very pleasing; and if you manage so as not to distress or embarrass your self with writing them, I care not how long they are – you may do as I do, Take a whole sheet, and fill it with Girl’s prattle as I do mine with Old Dad’s.”

Please help support

Irish Heritage News

A small independent start-up in West Cork

Give as little as €2

Thank You

At times his teasing feels relentless:

“But don’t you, Huzzy, in your Apology betray some Vanity? How come you to imagine that my not hearing from you the Evening of the day on which I left you, would make me uneasy? Especially as you observ’d, I did not bid you write. But thus young Damsels are wont to set a high Value on themselves and thence to fancy that others do.”

Synge was a devoted and loving father but ever critical. Alicia was a wealthy heiress and the bishop attempted to prepare her for the life that lay ahead of her. Most importantly, Synge wanted her to master the art of letter-writing, a necessary business skill for her future. He regularly corrected her spelling, grammar and expression. In doing so, he quotes some of her sentences and so, on occasion, we hear Alicia’s voice, if only momentarily. She affectionately calls him “Dear Dada”.

“Huzzy, you are still careless in Spelling, and in ten lines, I don’t see a Stop. A little care will mend this. Pray, My Dear, take it. I’ll note the false spellings in your last. For bear, you write bare. For shopping you write shoping. For patient, you write petient. These are but three: but they are three too many.”

The pair enjoyed gossiping about engagements, marriages and scandals but, in particular, the letters are filled with Synge’s observations on Alicia’s education, reading matter, manners, social conduct, exercise habits and tastes in fashion and music.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

The clergyman also fretted constantly over his daughter’s health and diet. This is hardly surprising since all the other family members were, by this time, deceased. It was on account of Alicia’s seemingly fragile constitution that Synge had her remain in Dublin, where she was regularly attended by a doctor, while he summered in rural Roscommon.

“It just comes into my mind to give you a little bit of advice about your Diet … You appear fonder of broil’d meats, and meats roasted high and brown, than of any other. I apprehend that both are bad for your little scurvy, which may grow worse, and invade your face.”

Though she was tall like her father, Synge expressed his hopes on more than one occasion that Alicia would be like his wife in all aspects except her ill health. Alicia was only about four years old when she lost her mother.

“I flatter my self that you are your good Mother’s daughter in understanding, as well as in feature. I pray God you may be like her in every thing, but her bad health. I can’t wish you any thing more for your advantage.”

Above all, Synge desired Alicia to marry well and become a mother. But, perhaps surprisingly for the time, both father and daughter strongly disapproved of child brides and opposed youthful marriages. Also, the bishop warned against marrying purely for money and regularly encouraged Alicia’s independence, driving her to make decisions for herself.

Upstairs, downstairs

In 1749 Synge employed 17 servants in Elphin, all Protestants. His letters are filled with many comical observations of the servants:

“Mrs Heap [the housekeeper in Elphin] … really does just nothing at all, but keep the Linnen and Grocerys, how well, I know not, nor do I enquire … Mrs Heap gave her Self no trouble. She lyes a bed till eight or nine, and then saunters about as she pleases. She spends most of her time in the Servants Hall, or in her own room, they with her; and as far as I can observe Darning, or pretending to darn is her chief employment. While I am away she has nothing to do, and therefore does nothing while I am here.”

“Tom’s [Synge’s valet] heighth and conceit grow every day less tolerable. Besides his near-sightedness disqualifys him for shaving me right.”

A F F I L I A T E A D

Synge also often harshly complains about “poor Stupid Shannon”, his steward at Elphin, who had broken most of the bishop’s water glasses. On more than one occasion, individuals in the employment of the Synges were dismissed on counts of drunkenness, dishonesty and idleness, as well as lesser misdemeanours.

“I cannot bear Supple [the butler at Elphin], and resolve to part with him when I go to town … He is glum sullen, conceited Fool, and plagues, I won’t say frets me every day of my life. So that I must get another or go without.”

Nonetheless, Synge regularly referred to his servants as “my family” and sent one of his Roscommon servants, “Poor Billy Beaty”, who had a sore leg, all the way to Mercer’s Hospital in Dublin for treatment. The bishop was on the hospital board.

The bishop’s achievements

In Dublin, Synge was a governor of the workhouse and the Blue Coat Hospital, a trustee of Dr Steevens’ Hospital and the treasurer of Erasmus Smith Schools (an educational charity), as well as holding positions on numerous other boards.

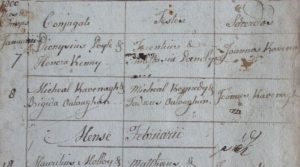

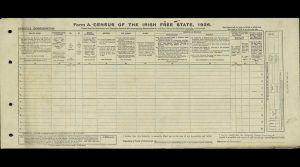

In 1749, Synge set out to establish the number of Protestants and Catholics residing in his diocese in what became known as the Elphin Census. This was an immense undertaking for the time, with nearly 20,000 households, of all denominations, recorded.

>>> RELATED: The 1749 Census of Elphin

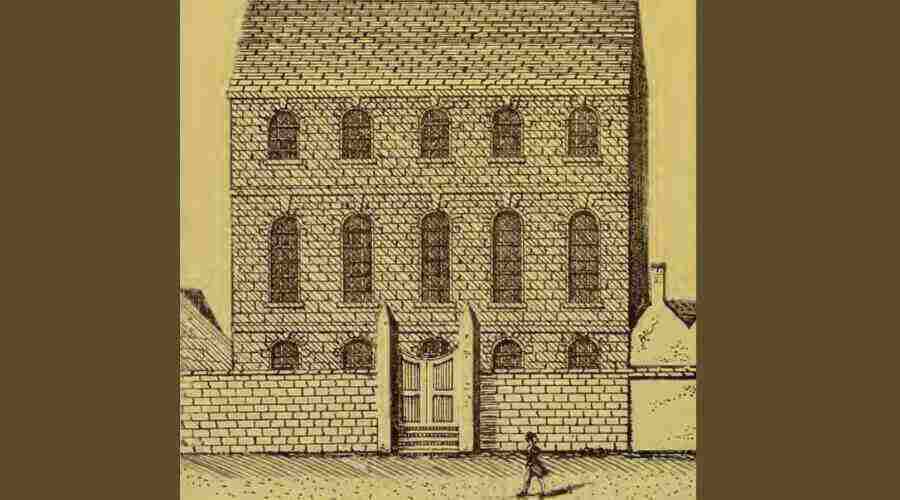

At Elphin, he also supervised the building of a new cathedral (now demolished) and an episcopal palace. Synge imported all sorts of flowers, trees and vegetables for his garden and park at Elphin; they also kept peacocks there. Some of the letters to Alicia are taken up with describing the building and furnishing of the new house. In 1747, Synge described his episcopal residence as follows:

“The Scaffolding is all down, and the House almost pointed, and It’s figure is vastly more beautifull than I expected it would be. Conceited people may censure its plainess. But I don’t wish it any further ornament than it has. As far as I can yet judge, the inside will be very commodious, and comfortable.”

A Palladian-style building, it comprised a three-storey, east-facing main block, with quadrants linking this block to wings on either side. The central block was destroyed in a fire in 1911 and later demolished. The two wings survive, of which the southern example was restored as a private residence about a decade ago.

Synge was a trustee of the Linen Board. The Roscommon soil suited flax growing and Synge promoted the linen industry locally. His letters often comment on the effect of the weather on flax growth in the region as well as on his own crop.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

A harpsichord player, Synge was musically talented. Composer George Friedrich Handel described him as “a Nobleman very learned in Musick”. Synge attended the first performance of Handel’s Messiah, which was performed in the new music hall in Fishamble Street, Dublin, in 1742. Handel’s concerts supported the fledgling Mercer’s Hospital.

Sign up to our newsletter

Aged approximately 71, Edward Synge died on 27 January 1762 and was buried in the family vault in the Vicar’s Bawn at St Patrick’s Cathedral, Dublin, where his wife had been laid to rest more than two decades before.

Alicia’s life

In her mid-twenties, Alicia married Joshua Cooper of Mercury (now Markree Castle), Co. Sligo, in 1758 in Elphin. She was then worth £50,000. An MP for Castlebar and Co. Sligo, Cooper voted against the Union.

The couple had three or four sons and a daughter, though sadly two of the children died in infancy. Cooper died in 1800 and his heir, Joshua Edward, was certified a “lunatic” soon after; the estate was then placed in the hands of the Masters of Lunacy in 1804.

Alicia passed away three years later in the Synge homestead in Kevin Street, aged about 74. It was said she died of a broken heart. She was buried in the Vicar’s Bawn at St Patrick’s Cathedral, near her dear dada.

Alicia’s descendants, the Coopers, preserved her father’s letters. They can be read in full in The Synge Letters: Bishop Edward Synge to His Daughter Alicia, Roscommon to Dublin, 1746-52.

Advertising Disclaimer: This article contains affiliate links. Irish Heritage News is an affiliate of FindMyPast. We may earn commissions from qualifying purchases – this does not affect the amount you pay for your purchase.

READ NOW

➤ Charting Judith Chavasse’s life in West Cork and Waterford through her diaries and memoirs

➤ The notorious Miler Magrath, simultaneously a Catholic and Protestant bishop

Gargett, G. and Sheridan, G. 1999. Ireland and French Enlightenment, 1700-1800. Springer.

Legg, M-L. 2009. ‘Synge, Edward’, Dictionary of Irish Biography.

[https://www.dib.ie/

biography/synge-edward

-a8427]

‘Saucy Mistress Boldface’ [podcast]. The Lyric Feature, RTÉ, 4 Apr. 2021.

[https://www.rte.ie/

radio/podcasts/

21934012-saucy-

mistress-boldface-

the-lyric-feature/]

Synge, E. 1996. The Synge Letters: Bishop Edward Synge to his daughter Alicia, Roscommon to Dublin, 1746-1752. Ed. by M-L. Legg. Lilliput Press: Dublin.

Synge, K. C. 1937. The Family of Synge or Sing. G.F. Wilson: Southampton.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T