Frances Sheridan was a pioneering 18th-century Dublin-born writer whose novels and other writing accomplishments contributed to Ireland’s early literary tradition and inspired generations of writers within her own family.

Early life

Frances Chamberlaine – or Miss Fanny as she was known – was born in 1724 to a family of English extraction. Her mother, Anastasia Chamberlaine (née Whyte), died soon after Frances was born and her father, Dr Philip Chamberlaine, was an Anglican minister and long-time rector of the Church of St Nicholas Within in Dublin city, where the family lived. As an infant, Frances suffered an accident and was slightly lame from then on, requiring assistance on long walks.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Although admired as a preacher, Dr Chamberlaine was considered eccentric by many and among his greatest aversions was female education. Writing, he believed, was wholly unnecessary for girls and women, as he claimed that this knowledge could only lead to the “multiplication of love-letters”.

Despite his opposition to his daughter’s education, Frances’ loving brothers helped with her studies by stealthily providing her with reading and writing materials. In particular, her eldest brother Walter instructed her in writing and Latin, while her brother Richard taught her botany. Frances herself went on to tutor a young male outcast in her father’s parish who was considered incapable of instruction. She succeeded in teaching him to read and repeat prayers.

Early writing efforts

At the young age of 15, unknown to her father, Frances composed Eugenia and Adelaide, a romance in two volumes. She wrote it on her father’s coarse, discoloured paper used for the household accounts. Published posthumously and without her name, the comic drama was later successfully adapted for the stage by her eldest daughter. Frances next tried her hand at writing a couple of sermons.

Thomas Sheridan

Dr Chamberlaine’s mental health began to deteriorate around the same time as Frances entered adulthood, which allowed her some extra freedom. She occasionally accompanied her brothers to the theatre. Before this, she had been unable to attend as her father strongly objected to such forms of entertainment. It was there that Frances first set eyes on Thomas Sheridan, a highly educated Anglo-Irish actor and theatre manager from Co. Cavan – his father was a close friend of Jonathan Swift, and Thomas was Swift’s godson.

Sign up to our newsletter

Theatre riots

Thomas had been enjoying a degree of success in Dublin’s Theatre Royal (i.e. Smock Alley Theatre in Temple Bar), but this was overshadowed in January 1746 by a series of events, which became known as Kelly’s Riot. This was sparked when Mr Kelly from Galway forced his way backstage at the theatre in an attempt to pursue the celebrated Irish actress George Anne Bellamy. Thomas valiantly came to her aid, rebuking Kelly, upon which a scuffle broke out involving the two men.

Claiming he had been beaten by Thomas, Kelly gathered a band of his friends who vowed to avenge him. They returned to the theatre on several occasions to issue threats and cause disturbances. Others in literary and college circles began to rally behind Thomas and publicly display solidarity with him. Among them was Edmund Burke, then a student and later the renowned political theorist remembered for his support of Catholic emancipation.

A paper written in Thomas’ defence appeared in Faulkner’s Dublin Journal on 25 January 1746. It was followed by an anonymous pamphlet filled with poetic verses penned by Frances. Despite every attempt made to defend Thomas, a riot took place in the theatre one night when he was due to perform on stage in a charity play. This disturbance led to a series of arrests and Thomas was tried for assaulting Kelly, but was immediately acquitted on the grounds that Kelly had provoked him.

A F F I L I A T E A D

Kelly was subsequently tried, found guilty, fined £500 and sentenced to three months in prison. The fine was remitted at Thomas’ request and, remarkably, he stood as solicitor and bail for the same man who had once threatened his life. His popularity – and that of the theatre he managed – rose significantly as a result of this act of generosity.

The impressive pamphlet championing Thomas’ cause ultimately led to an introduction between him and Frances once the riots had come to a conclusion.

Marriage and family life

Thomas and Frances were soon married in 1747. They lived comfortably in Upper Dorset Street in Dublin, but also spent time in Thomas’ family home in Cavan. Thomas had purchased this country residence, called Quilca House, from his brother and it was there that Frances was at her happiest. This is also the house where Jonathan Swift wrote parts of Gulliver’s Travels and later immortalized it in his Quilca poems.

Between 1747 and 1758, Frances gave birth to six children. Sadly, one of their sons, Sackville, died as an infant, while their eldest child, Thomas, died at the age of three. Frances’ maternal tenderness has often been commented upon, and it has also been acknowledged that she excelled in every aspect of domestic affairs.

Her calm, composed disposition and affectionate nature helped to forge pleasant childhood memories in the minds of each of her children who reached adulthood. In the 1740s and 1750s, Frances devoted herself to raising her young family, which left little time for writing.

More rioting

In the early years of their marriage, Thomas continued in his role as manager of Smock Alley and became a revolutionary figure in the development of theatre in Ireland. However, he soon found himself embroiled in further drama after forming an elite theatrical club of intellectuals, mainly politicians, commonly dubbed the “Beef-Steak Club”. Unusually for the time, the Irish actress Margaret (Peg) Woffington was elected president of the club in 1753. She was known for her dislike of her own gender, declaring that “the conversation of women consisted of nothing but silks and scandal”.

>>> YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: Curtains up: a nostalgic look at Cork’s old opera house and the Harold Pinter connection

Given the involvement of political figures in the club, non-members working in theatre and members of the public began to display dissatisfaction. Thomas insisted on the professional dignity of actors by removing audience members from the stage and directed the actors not to repeat speeches attacking the government, as demanded by the public during stage performances. His instructions, however, were disregarded. Some have claimed that Thomas allowed the actors to perform such speeches at their own discretion, while others have commented that he attempted to censor the actors.

Whatever the case, rioting erupted at the theatre one night in March 1754, largely prompted by the actor Mr Digges, who was known for disobeying the manager’s commands. Feeling threatened, Thomas quickly exited the building and set off home. Much of the theatre’s property was destroyed as rioters searched in earnest for him.

News of the riots reached his family before he arrived home. A servant, exaggerating the events, informed Frances that the theatre was in flames and that her husband’s life was in imminent danger. Frances was then heavily pregnant with Sackville, and it was believed, at the time, that the shock she experienced contributed to the infant’s premature death just three months later.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Shifting fortunes

On hearing of the outrages, the Duke of Dorset offered Thomas a generous annual pension of £300, but he declined, believing that it would only serve to reinforce the idea that he was cosy with the government. Convinced that public opinion was against him, Thomas relinquished the management of the theatre and sub-let it for two years. He then moved to England, leaving behind his wife and children, but returned to Ireland in 1756 and resumed his duties as theatre manager. By this time, the dust had settled and his theatre colleagues welcomed him back.

Frances was by now spending much of her time at a retreat in Glasnevin, where she could enjoy her children’s company and they could all breathe cleaner country air. But the family’s fortunes were set to turn once again with the opening of a new theatre in Dublin in 1757. Many of Thomas’ best performers moved to the new establishment, and naturally much of the regular Smock Alley audience followed.

>>> YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE: The American tours of the Dublin Players, 1951–58

For some time now, Thomas had been turning his attentions to literary pursuits and so, without too much difficulty, he once again left the theatre. Frances and Thomas, accompanied by their son Charles Francis, headed for London, while the other two children, Richard Brinsley and Alicia, remained in Ireland in the care of relations. Richard and Alicia later boarded in a newly opened grammar school on Grafton Street, now the site of Bewleys, run by Frances’ cousin Samuel Whyte. About a year and a half later, the Sheridans sent for Richard and Alicia to join them in their new home on Henrietta Street in Covent Garden.

A F F I L I A T E A D

Life in London and a return to writing

In 1758, Frances gave birth to a baby girl in London, the only one of their offspring born in England. Thomas was now busy perfecting his system for teaching English elocution, while also enjoying a degree of stage success at Drury Lane Theatre, alongside the renowned David Garrick – although tensions and rivalry existed between the two actors.

In England, Frances found herself surrounded by a circle of distinguished friends, among them the writer Samuel Richardson, who encouraged her to write after perusing her early novel Eugenia and Adelaide. Another supporter in re-igniting her literary talent was the author Sarah Fielding, sister of the novelist Henry Fielding. With this encouragement, Frances returned to writing, producing The Memoirs of Miss Sidney Bidulph, which was written in diary format and faithfully paints a picture of the life of a middle-class woman in the mid-18th century.

During the course of composing this work, Frances looked upon Richardson as her guide and only told her husband about the novel after it was completed. It is said that she kept a small trunk beside her while writing, in which she hid the manuscript whenever Thomas entered their home. The text was published in 1761 and became an instant success, soon being translated into French. A friend of the family, the distinguished writer Samuel Johnson (better known as Dr Johnson), humorously remarked upon its content:

“I know not Madam ! that you have a right, upon moral principles, to make your readers suffer so much.”

To date, The Memoirs of Miss Sidney Bidulph remains her best-known work, with several editions having been published.

Please help support

Irish Heritage News

A small independent start-up in West Cork

Give as little as €2

Thank You

By 1762, Thomas was receiving a £200 annual pension on the grounds of his literary merits, which indicates the royal favour shown to him. He was now engaged in rewriting the English dictionary, while the family were spending much of their leisure time in Windsor. They enjoyed walking in Windsor Park, and on one occasion the eldest daughter, Alicia, innocently brought home a fawn she had found in the royal enclosures – a hanging offence no less!

That summer in Windsor, Frances began to write her first comedy and theatrical essay, The Discovery. She read it to Garrick, who stated that it was “one of the best comedies he ever read” and begged her to permit him to perform it on stage. By this time, Frances’ health was deteriorating and she was experiencing intervals of illness. In February 1763, The Discovery was first performed to great success at Drury Lane, with both Thomas and Garrick playing parts.

Frances soon finished another comedy, entitled The Dupe, but it never achieved much success. Unfortunately, Thomas was now away on business in Dublin, and in his absence, she most keenly felt this blow to her literary career. This disappointment, combined with her husband’s absence, prompted her to write the poem “Ode to Patience”.

Thomas returned to England in the spring of 1764, which lifted her spirits once again. Frances then toured with him as he gave lectures on oratory in Bath, Bristol and Edinburgh. On one occasion, she returned on her own to London, where one night, while deeply engrossed in reading in bed, her curtains caught fire. Thankfully, the blaze was quickly extinguished, but Frances never again indulged in reading in bed by candlelight.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Life and literary pursuits in France

In September 1764, the Sheridans moved to France, drawn by the considerably lower cost of living. All of their children accompanied them except Richard, who remained in the care of Dr Robert Sumner, a master at Eton and later headmaster at Harrow.

Settling eventually in the city of Blois, the family lived a rather quiet life due to their financial struggles, as their affairs were now somewhat disordered. Because France was a Catholic country, Thomas established a Church of England service for his family, read by him every Sunday, which attracted a small Protestant congregation. Nevertheless, the family integrated well, befriending and regularly visiting Catholic clergy, including Fr Mark, an Irish Capuchin priest. The children exchanged gifts with friendly nuns in the neighbourhood, and Frances was taught music by a Jesuit on the Spanish guitar.

During their first year living at Blois, the mild climate seemed to improve Frances’ health, allowing her to resume writing. Over the next two years, she delved into the genre of the oriental tale, composing The History of Nourjahad, an instructive moral fiction that promotes the idea that true happiness depends on the regulation of the passions, rather than on outward prosperity. The idea for this poetical work came to her as she reflected on the inequalities of men.

Sign up to our newsletter

The History of Nourjahad was published posthumously in 1767 and enjoyed considerable popularity, being translated into French, Russian and Polish, and later dramatized by Sophia Lee, author of a series of Canterbury Tales.

During her time in Blois, Frances also added two additional volumes to The Memoirs of Miss Sidney Bidulph, the second and third volumes only being released after her death. In addition, she wrote another comedy, A Trip to Bath, but this was never fully completed, although Garrick expressed interest in staging it.

Decline in health and untimely death

In autumn 1766, Thomas was due to make an extended visit to Ireland, while Frances and the children were to remain in Blois. Frances planned to spend the time teaching her eldest daughter. Their impending separation, which obliged Frances to remain in a foreign country, the language of which she imperfectly understood, played heavily on her mind.

A few days before Thomas was due to leave, Frances was suddenly seized with a fainting fit and a low fever. Witnessing her strength rapidly decline, Thomas decided against leaving. For two weeks, she issued domestic orders from her sickbed and retained her senses until the day before her death.

Frances passed away peacefully at the age of 42, in the presence of her loving husband. She was buried in a private cemetery owned by a Protestant family just outside Blois. The funeral entourage was escorted by a procession of military men, but it took place at night by torchlight to avoid any conflict with Catholics, though some Catholics did form part of the party of dragoons.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Frances Sheridan’s legacy

Frances Sheridan’s legacy cannot simply be measured by her literary output, which is regrettably small, but must also consider the achievements of her children, to whom she devoted herself wholeheartedly. All four children who survived to adulthood followed in their mother’s footsteps.

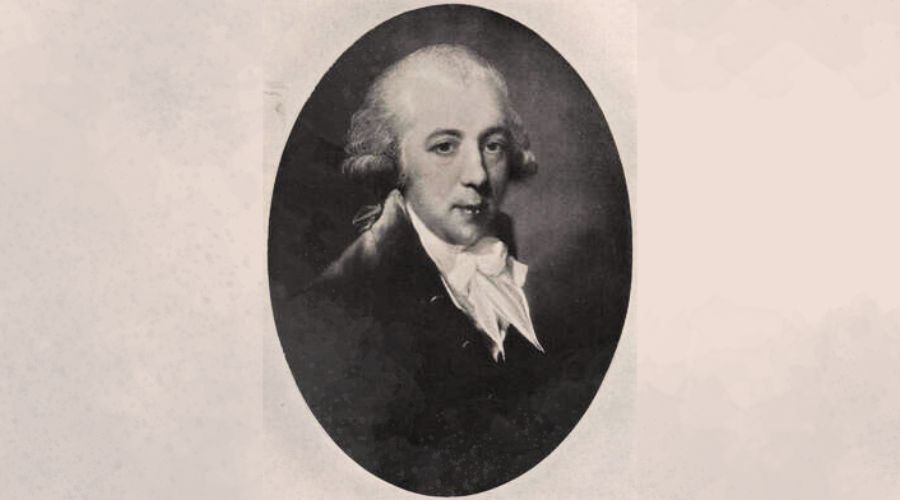

Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751–1816) became a world-famous playwright, poet and satirist. His mother’s incomplete and unperformed play A Trip to Bath (only published in 1902) had a significant influence on his work and is said to have inspired his comedic play The Rivals. Richard was also a politician. Although he left Ireland at a young age, he campaigned for Irish independence, developed ties with the United Irishmen and devoted himself to the cause of Catholic emancipation.

Richard’s older brother, Charles Francis Sheridan (1750–1806), was also a politician and a skilful pamphleteer. In May 1772, he was appointed secretary to the British envoy in Sweden and later wrote A History of the Late Revolution in Sweden, which was well received and translated into French. In 1793, he published two pamphlets: the first an essay defending Ireland’s rights as an independent kingdom and the second a statement supporting Catholic relief and defending Edmund Burke.

As a result of her own upbringing, in which she was forced to study in secret, Frances placed great importance on the education of her daughters. Both daughters also wrote. The eldest, Alicia Sheridan Lefanu (1753–1817), wrote a play, Sons of Erin, which was produced in London in 1812, while the journals of Frances’ youngest daughter, Anne Elizabeth (Betsy) Sheridan Lefanu (1758–1837), were published in 1960.

Much of this article is based on the biography of Frances Sheridan published in 1824, written by her granddaughter Alicia Lefanu, also a poet. These female writers remain largely understudied.

An earlier version of this article first appeared on Herstoric Ireland (www.herstoricireland.com – no longer online). Reproduced here with permission.

Advertising Disclaimer: This article contains affiliate links. Irish Heritage News is an affiliate of FindMyPast and the British Newspaper Archive. We may earn commissions from qualifying purchases.

READ NOW

➤ Life’s unexpected turns for the Mayo-born Margaret Martin who almost boarded the Titanic

➤ The “Lady of the Lake”: Beezie and her island

➤ Cork doctor’s reflections on service in North Africa and Italy during World War 2

➤ “Rebel Wife” film tells the story of Clonakilty heroine Mary Jane O’Donovan Rossa

➤ A rare glimpse of how gentry women in Co. Cork lived and ran their households

A D V E R T I S E M E N T