In this genealogy guide, we examine the value of marriage settlements for Irish family history researchers. These legal agreements, which were not limited to the landed gentry as commonly believed, offer a window into familial relationships and the socio-economic circumstances of past generations.

What is a marriage settlement?

A marriage settlement, also known as a “marriage article”, was a prenuptial agreement arranged by the families of the prospective bride and groom. Unlike modern prenups, marriage settlements were generally drawn up to safeguard the interests of one or both parties when the marriage ended in the event of a death rather than divorce.

Marriage settlements were typically drafted by the parents or guardians of the prospective bride and groom, usually with the primary aim of protecting the family estate, but they often sought also to protect the interests of any children resulting from the marriage and the future widow, should her husband predecease her. As such, marriage settlements provided security to women at a time when married women could not own property.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

A review of Irish marriage settlements shows that the dowry (also called a “marriage portion”) was often bestowed upon trustees rather than being given directly to the future husband, thereby ensuring a measure of security for his future wife if he were to die first. In such instances, some settlements for wealthier couples also granted an annuity to his widow and any children they should have.

Less commonly, marriage settlements were arranged to protect, in the event of a disagreement, another family member who intended to reside with the couple, such as the mother of the bride or groom, or an aunt or uncle.

Given that marriage settlements generally document transfers of cash, property, land or other assets, the upper echelons of society, with their substantial resources, are best represented within these records. However, while it’s commonly thought that only the wealthy arranged marriage settlements, such agreements were not unusual by the 19th century, even among small farmers.

>>> READ MORE: Three siblings marry three siblings in unusual triple wedding in west Clare

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, many marriages in rural Ireland were arranged by matchmakers. The matchmaker was usually a trusted individual who was well known to both families. Before the wedding, specific terms would be agreed upon and a legal contract would be drawn up and signed by the two parties.

What info is included in a marriage settlement?

Marriage settlements provide a good deal of useful information for the genealogical researcher. The level of detail varies greatly, but these documents often span several pages. The general rule of thumb is that the wealthier the parties involved, the more detailed the contracts tend to be.

Most marriage settlements list the names, addresses and occupations of the prospective bride and groom. There’s often detailed information about assets and a detailed provenance of the lands and properties involved.

Sign up to our newsletter

Marriage settlements usually provide a good deal of information about the bride and groom’s parents and often other family members too. Sometimes, marriage settlements name the members of several generations within a family helping you to trace your ancestry further back. They can also refer to previous marriages, mistresses and children from previous marriages or born outside wedlock. Details like ages and dates of important life events are sometimes stated.

Some marriage settlements refer to earlier records to explain the property’s history, thereby opening up more avenues to investigate. They may refer to previous or existing agreements with landlords, tenants, the Irish Land Commission or the Estates Commissioners Office. They may cite earlier marriage settlements, wills, mortgages and leases.

>>> READ MORE: Tracing your roots online using old records of Irish gravestone memorials and “Mems Dead”

These pieces of information can serve as a gateway to discovering even more about earlier generations. Marriage settlements are especially useful for the period before 1864 when the civil registration of births, deaths and marriages was enforced legally. They can also be useful to bookend the length of time an individual was resident in a particular place. It can be hard to find information about women in Ireland before the mid-19th century but, as well as the prospective bride, the mothers of the bride and groom frequently feature in these records.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Where can I find my ancestor’s marriage settlement?

Typically, there were at least two original copies of the marriage settlement, which were kept by the two parties or their legal representatives. Even today, some families still possess the original marriage settlement or a copy in their own family collection.

Some marriage settlements may still be held in the family solicitor’s office. The potential for this is greater when the land has remained within the same family being passed down through the generations and the likelihood also increases when those families continue to use their local solicitors with longstanding practices.

Please help support

Irish Heritage News

A small independent start-up in West Cork

Give as little as €2

Thank You

Some marriage settlements were registered with the Registry of Deeds in Dublin. Registration was not compulsory in Ireland, though a registered deed had priority over an unregistered deed, so those with the means and know-how to register a marriage settlement often opted to do so. There was also a strong incentive to register the marriage settlement if it was believed that a future dispute could arise or if it was feared that the marriage settlement could be questioned sometime in the future.

The Registry of Deeds commenced in 1708 and most of the earlier marriage settlements that were lodged were those belonging to the landed gentry. From the 1780s, when the Penal Laws were relaxed, more people had recourse to the Registry and some marriage settlements between parties of modest means were registered, especially in the 19th century.

>>> READ MORE: Leap year dances in Ireland 100 years ago

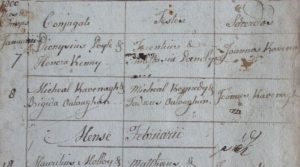

Original marriage settlements are not held in the Registry of Deeds, but their collections contain “memorials” of marriage settlements. A “memorial” is essentially a verbatim copy of the original marriage settlement or a detailed synopsis that the Registry of Deeds registrar or clerk drew up. The marriage settlements were transcribed in full into Transcript Books and specific details were extracted and entered into the Grantors Index and Land Index.

The Registry of Deeds records are held in various manuscript, microfilm and electronic formats in their office on Henrietta Street in Dublin, which is open to the public. There, you can view the records in person but appointments must be made in advance through their online booking system.

A F F I L I A T E A D

However, you may not have to travel all the way to Dublin to access the Registry of Deeds records you require. The website FamilySearch.org has made microfilmed images of the Transcript Books (which they call “Memorial Books”), Grantors Index and Land Index (also called “Place name Index”), covering the period from 1708–1929, available to view online for free.

The content of these records has not been transcribed on the FamilySearch website; this makes searching these records a time-consuming exercise. However, the volunteer-led Registry of Deeds Index Project has indexed and transcribed the essential details of a sizeable portion of the records, which can be searched for free. Perhaps you’ll be lucky enough to find your ancestor’s marriage settlement in their database.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

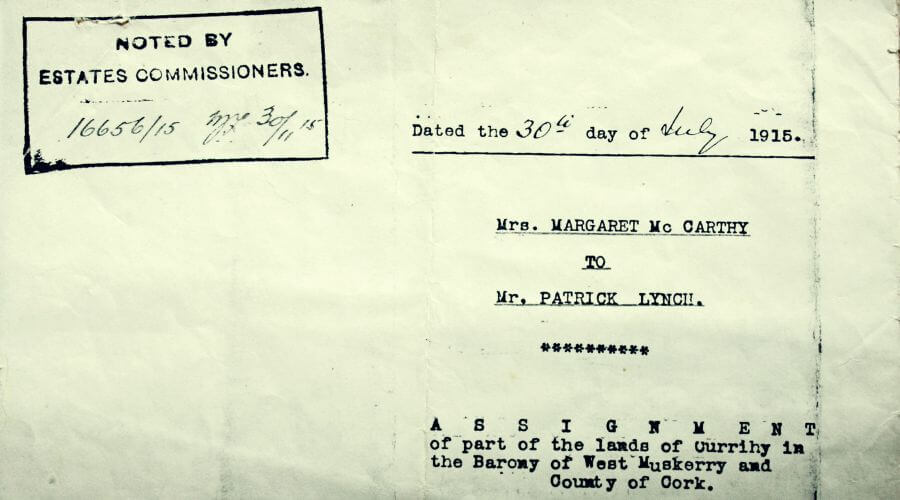

A 1915 marriage settlement from Co. Cork

In post-Famine rural Ireland, the eldest son typically inherited the farm from his father but by the early 20th century, it was not uncommon for a man to “marry into land”. A man marrying into land was known in Irish as “cliamhain isteach” and on his marriage, he was expected to pass over a “fortune” (similar to a woman’s dowry) to his future wife’s parents in order to be assigned the land.

One such example of this occurrence was the marriage of Patrick (Paddy) Lynch from Inchinahoury in the civil parish of Clondrohid in Co. Cork to Helena (Nellie) McCarthy from Currahy in the neighbouring civil parish of Inchigeelagh. In addition to their marriage settlement, other genealogical records and family lore are drawn on below to help expand the family history.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

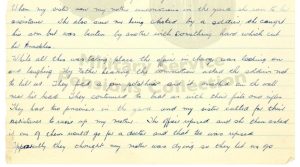

On 31 July 1915, Nellie and Paddy wed in the Catholic church in Ballingeary. This was only their third time meeting; Nellie was not quite 21 and Paddy was 31. They were married by Fr James O’Callaghan, who was later shot dead in Cork city by Crown forces during the War of Independence.

Prior to their wedding, a marriage settlement was prepared to facilitate the transfer of land. On the day before the wedding, Nellie’s mother, Margaret (a widow) and Paddy signed an indenture bestowing the small McCarthy family farm in Currahy to Paddy. In exchange, Paddy, who had spent several years in the United States, parted with £375, which he handed over to Margaret on the very same day.

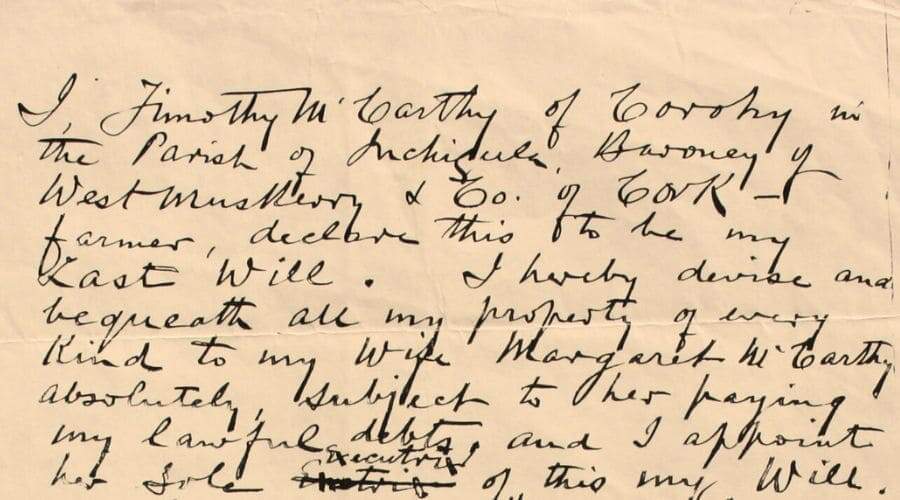

Margaret had been left the farm in Currahy in its entirety by her husband Timothy McCarthy, a tenant farmer, when he died in 1906. They had eight children together, one of whom had died at the age of three in 1889. Timothy also had two children from a previous marriage and one of them had also died in infancy shortly after his second marriage in 1881.

By 1915, the only children remaining at home with Margaret were Nellie and her two younger brothers: Jeremiah, aged 18 and Jack, aged 15. All of Nellie’s older siblings had emigrated to the United States, except for her eldest brother Denis, who had left home to work for another farmer.

The McCarthy farm had been part of the estate owned by Col. Jemmett Browne. Under the provisions of the Irish Land Act 1903, Margaret had agreed to purchase the 54-acre farm “in fee simple” for a sum of £174 and had sought an advance of this amount from the Irish Land Commission. By 1915, Margaret may have found herself in need of a cash injection to settle debts related to the farm, including the outstanding payment owed to the Land Commission.

A F F I L I A T E A D

And so, Margaret decided to seek a match for her 20-year-old daughter. With the help of Con Lynch, a relative of Paddy’s and a neighbour of the McCarthys from nearby Turnaspidogy, a match was arranged between Nellie and the recently “returned yank”, who was on the lookout for a farm.

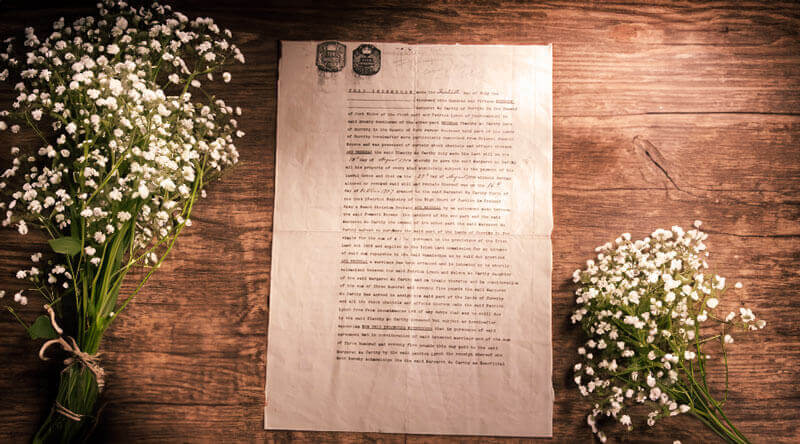

The two-page marriage settlement refers to the will made by Timothy McCarthy granting his wife Margaret “all his property of every kind absolutely subject to the payment of his lawful debts” and to the agreement between Margaret and the landlord Jemmett Browne to purchase this property for the sum of £174, with the support of the Land Commission.

The marriage settlement further stipulates that in consideration of the sum of £375 and the intended marriage between Paddy and Nellie, Margaret was transferring the land and “all the stock, chattels and effects” to Paddy free from any incumbrances and any debts affecting the land. The chattels and effects included stock, cattle, farming implements, dairy utensils, household furniture and “all other chattels and effects of every nature and kind on said lands”.

In return, Paddy agreed to “support, maintain, and keep” Margaret in the dwelling house on the farm “according to her station in life”, granting her “the use of the room containing the fireplace attached to the kitchen”. Margaret was ensuring her own comfort and wellbeing in their shared home.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

However, in the event of a disagreement between Paddy and his future mother-in-law, the following conditions were agreed upon: Paddy was to provide Margaret with the use of the aforementioned room together with

“the bed and bedding therein, three bags of potatoes and eight cribs of turf yearly, one quart of sour milk and one pint of new milk daily and a half a pound of butter weekly together with the sum of six pounds yearly payable half yearly from the date of said disagreement.”

Thankfully, no such disagreement occurred. Paddy and Nellie enjoyed a happy life together, raising 10 children until Paddy passed away in 1948. Margaret lived in harmony with the family, actively contributing to the household and helping to rear the children. She was well looked after until her death at the advanced age of 87, having outlived her son-in-law by two years.

Advertising Disclaimer: This article contains affiliate links. Irish Heritage News is an affiliate of FindMyPast. We may earn commissions from qualifying purchases – this does not affect the amount you pay for your purchase.

READ NOW

➤ Did your ancestor spend time in a workhouse?

➤ A guide to navigating Northern Ireland’s church records

➤ Find your ancestors in Ireland’s historical school records

➤ Irish civil records: what’s online and what’s not online?

➤ A genealogist’s guide to DNA testing for Irish family history research

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

One Response

Thank you for this exceptionally well written and informative article. I look forward to reading more articles on your site.