We explore the fact and fiction behind a Roscommon folktale concerning the apprehension of a priest and subsequent rescue by force moments before he was to be hanged.

The folktale

In c.1937, Strokestown schoolgirl Betty Murray recorded a local folk story involving a priest who, during penal times, was to be hanged just outside the village of Cootehall in northern Roscommon. Soldiers gathered at the execution site, while Catholics assembled on a nearby hill where they hatched a plan to save the priest. An unnamed man who was “more or less intoxicated, but … a crack shot” came forward and fired at the hangman, killing him. The soldiers dispersed and the locals saved the priest, or so the story goes.

Betty collected this tale from 68-year-old William Madden from Farnbeg as part of the nationwide Schools’ Folklore Collection.

Fact or fiction?

Irish Roman Catholics had been suppressed from as early as Tudor times but between 1695 and 1756, this suppression intensified with the introduction of the penal laws, which were imposed on both Catholics and Protestant dissenters to encourage them to accept the established Anglican Church of Ireland; they were not fully removed until 1829 with Catholic emancipation.

We must bear in mind that the folktale recalling the liberation of the Roscommon priest was written down much later, in c.1937. As to the authenticity of the story, it seems to be grounded in some truth, though the finer details may have been somewhat misconstrued.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Following the Williamite War, religious persecution escalated in Ireland. The penal laws forbade any manifestation of the Catholic religion, but the extent to which the legislation was enforced differed from place to place and changed over time.

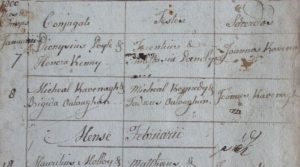

In 1697, under the terms of the Banishment Act, all Catholic bishops and “regular” clergy (those belonging to religious orders) were instructed to leave Ireland. By 1704, priests were obliged to register, but only one priest could be registered per civil parish. A comprehensive record of all registered priests was drawn up.

All other priests were not allowed to minister and were obligated to leave the country, while no priests were allowed to enter from abroad. But soon, even registered priests were targeted.

Please help support

Irish Heritage News

A small independent start-up in West Cork

Give as little as €2

Thank You

In 1709, the Abjuration Act obliged all priests to renounce the Jacobite claim to the British throne, which related to the movement supporting the restoration of the Catholic House of Stuart. The oath declared acceptance of Queen Anne as the lawful queen. If a priest did not swear this oath by 25 March 1710, he would be liable to arrest and deportation.

However, the pope decreed that no Catholic could take the oath and so most refused but by doing so, they forfeited any legal protection that the Registration Act had provided registered priests. Consequently, priests were forced into hiding and Catholic mass houses were abandoned. A reward of £20 was offered for the discovery of clergymen leading to their apprehension.

>>> READ MORE: Recording Ireland’s mass paths through the voices of Irish emigrants in New York’s Tri-State area

To overcome the obstacles to their faith, Catholics created new secret spaces for worship and rituals. They gathered at remote locations to attend Mass, sometimes outdoors under trees, in ditches and at stone altars known as mass rocks, and other times indoors in small secluded chapels or private dwellings as in the case of an incident in Westport, Co. Mayo, for example. In April 1715, registered parish priest Fr Patrick Duffy came before the assizes for the Connacht circuit for saying Mass in Thomas Joyce’s home in Westport; Fr Duffy was also believed to be one of the vicar generals of the diocese of Tuam. Despite the dangers inherent in harbouring priests, this incident illustrates that parishioners used their houses to shelter clergymen.

The true story

In that same year – 1715 – it is recorded that no priests in Co. Roscommon had abjured. As a result, a determined effort was made at this time to round up the Roscommon clerics, which outraged locals.

Sign up to our newsletter

A case concerning a Franciscan friar from Roscommon named James Kilkenny attracted widespread attention. He had evaded the law for four years, but various primary documents record that the friar was arrested in October 1715. When being transported to Roscommon prison, the constables accompanying him were set upon and beaten by a group of locals while the prisoner was rescued. This may well be the true story behind what was documented by Betty Murray over two centuries later.

The saviours

The group of local Catholics who helped Friar James Kilkenny comprised both men and women. George Gore, Attorney General of Ireland, was ordered to prepare a proclamation promising a reward for capturing the cleric and anyone involved in the rescue operation. Issued on the 7th (or 11th) of November 1715, it offered a £100 reward for the apprehension of the cleric and £20 for the apprehension of his rescuers, who were named as Patrick Baken (or Beakin), Una McManus and Margaret Tristan. The reward was also extended to the capture of anyone else involved in the rescue.

In the dead of night, Patrick Baken was arrested along with Mary Baken. They were from the townland of Carroward, about 5km south of Cootehall village: the scene where Betty Murray’s story took place. Patrick and Mary were both tried at the summer Roscommon assizes in 1716, with Mary being found guilty of her involvement in the rescue operation and fined £20. It is highly unlikely that she would have had the means to pay this. Further details of the trial have been lost, but we may assume that Patrick fared no better.

A F F I L I A T E A D V E R T I S E M E N T

The captor

Additional information possibly concerning the same event can be found in the Schools’ Folklore Collection and was provided by Knockvicar student May Molloy. May speaks of a priest who escaped while in the custody of a man named Coote of Cootehall. She added that he “was always priest hunting”.

The Coote family settled first in Laois. The head of the family was granted the title Earl of Mountrath in the 1660s and was granted over 4,200 acres in counties Roscommon and Galway, along with over 15,000 acres in Leinster, while his brother was granted over 3,800 acres in Roscommon in 1674. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the 4th and 5th baronets lived at Coote Hall, a castle on the edge of the village of Uachtar Thíre, which, in time, also became known as Cootehall.

While relatively little is known of the phenomenon of the men who hunted down the outlawed Catholic clerics for a cash bounty, there is evidence that the Coote family was engaged in such activity and may have had a long history in this department. Sir Charles Coote, who built Coote Hall, was appointed provost-marshal of Connacht in 1605 and would have had sweeping powers to deal with the disorderly or anyone deemed to be acting outside the law. But it is Colonel Chidley Coote who is of greater interest in the context of this story. In 1709, he served as high sheriff of Leitrim and the state papers reveal that in 1711–12, he was responsible for committing priests arrested in Co. Sligo to jail. However, no member of the Coote family is named specifically in reference to the case of Friar James Kilkenny.

It may be that the stories recorded by pupils May Molloy and Betty Murray are the result of several different events woven together over time.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Would he have been hanged?

May Molloy wrote that Coote “had a hanging place at a gateway leading to his house”. Coote Hall was built at the beginning of the 17th century but was burned in 1798 and was subsequently replaced by a farmhouse. Access to the house is via an avenue and a fine gateway, which still stands (see image below). It is a pedimented triple-arched stone entranceway with a large central vehicular opening and with a smaller pedestrian opening to either side.

However, this particular gateway dates to c.1780, about half a century after the event involving Friar James and there is no further evidence indicating that this was the site of public executions.

The village of Knockcroghery, in southern Roscommon, derives its name from the Irish “Cnoc an Chrochaire”, meaning the “Hill of the Hangings”. The small but prominent hill in the townland of Creggan, at the northern end of the village, is commonly known as “Hangman’s Hill”. Tradition has it that during Cromwell’s campaign, Sir Charles Coote hanged the O’Kellys of nearby Galey Castle at this location when they refused to submit. Similarly, the nearby townland of Gallowstown (Lisnacroghy) is said to have acquired its name following executions undertaken there by Coote. However, The Compossicion Booke of Conought is the earliest source recording the name “Lisnecrohie” and it dates to 1585, some 15 years before the arrival of the Cootes to Ireland.

Nonetheless, the traditions surrounding these two placenames demonstrate that in Irish folklore, the Cootes had a reputation for carrying out executions, though the lore relates to the period prior to the introduction of the penal laws.

A review of the national folklore collection reveals many more stories concerning outlawed priests and priest-hunters in this region of Connacht. Some were not as fortunate as Friar James. One such priest, we are told, was shot dead while saying Mass at a mass rock at Kilmactranny (Carrickard), Co. Sligo, about 12km northwest of Cootehall. The entry in the Schools’ Folklore Collection records that the “image of his knee is still in the rock”; this idea of the supernatural transformation of the rock as a result of the killing of a priest is somewhat common in Irish folklore.

Research undertaken over the past decade by Dr Hilary Bishop (Liverpool John Moores University) into the myths and folkloric narratives pertaining to the penal period shows that there is little historical basis for the popular belief that priests were regularly murdered at mass rocks. Her work highlights that the penal era priest was a hunted man who endured much hardship, but historical records indicate that they were more likely to be imprisoned during the penal period rather than killed.

However, we do have some reports of priests being executed. For example, the Ipswich Journal reported on 29 April 1727 that in Limerick,

“Father Riley a Popish Priest was try’d there for marrying a Roman and a Protestant together, contrary to Law, for which he was found guilty and received Sentence of Death, and accordingly was executed … much lamented by many of the Country People.”

In the case of Friar James Kilkenny, it appears that he was never recaptured and it is difficult to determine his fate had he been less fortunate. May Molloy noted that the priest who had escaped Coote’s hands fled to Ballyformoyle, about 5km north of Cootehall, where he “said daily Mass on the mountain for several years”.

Advertising Disclaimer: Irish Heritage News is an affiliate of FindMyPast – we earn commissions from qualifying purchases. This does not affect the amount you pay for your purchase.

READ NOW

➤ Maolra Seoighe: the hanging of an innocent Connacht man

➤ Clogagh: a small West Cork community transformed by the Revolution

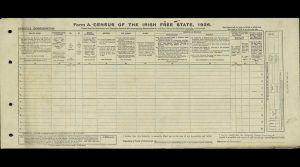

➤ What the census tells us about Ireland’s first president, Douglas Hyde

➤ Fr Lorcán Ó Muireadhaigh and the founding of “An tUltach” (The Ulsterman) in 1924

Archaeological Survey of Ireland.

[https://maps.archaeology.ie/

HistoricEnvironment]

Bishop, H.J. 2018. ‘Memory and legend: recollections of penal times in Irish folklore’. Folklore 129(1), pp.18-38.

Bishop, H.J. 2019. ‘Keeping the faith: the role of the Irish house during the penal era and beyond’. Review of Irish Studies in Europe 3(1), pp.1-16.

Burke, W.P. 1914. The Irish Priests in the Penal Times (1660-1760). N. Harvey and Co.: Waterford.

D’Alton, J. 1845. The History of Ireland, from the earliest period to the year 1245, when the Annals of Boyle, which are adopted and embodied as the running text authority, terminate: with a brief essay on the native annalists, and other sources for illustrating Ireland, and full statistical and historical notices of the barony of Boyle. Vol. 1. Dublin.

Irish Press, 15 May 1959.

Jefferies, H.A. 2009. ‘Penal days in Clogher’. History Ireland 17(3).

[https://www.historyireland.com/

penal-laws/penal-days-in-clogher/]

Kelly, J. and Lyons, M.A. 2014. The Proclamations of Ireland 1660–1820 Volume 3. Irish Manuscripts Commission: Dublin.

Murphy, C. 2013. The Priest Hunters: The true story of Ireland’s bounty hunters. O’Brien Press.

National Inventory of Architectural Heritage.

[https://www.buildingsofireland.ie/]

Placenames Database of Ireland.

[https://www.logainm.ie/]

Schools’ Folklore Collection, vol. 233, pp.514-15; vol. 253, p.169; vol. 259, pp.271-72. National Folklore Collection, UCD.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

One Response

I love Irish history. My late Mum and Dad were born in a beautiful village in county Limerick, north of Mitchelstown, on the foothills of the Galtee mountains, Ballylanders. I learnt a lot about the history of this beautiful part of Ireland.