By Fiona Forde

Conducting efficient Irish genealogical research requires a basic understanding of the various forms of land division in Ireland. In this guide, Fiona Forde, aka the Irish Family Detective, introduces us to Ireland’s unique townland system. Exploring the administrative categorization of townlands and tracing the evolution of their names over time, this guide highlights the relevance of townlands for genealogical researchers.

Origins of the townland system

While people are the main driver in the study of local history and genealogy, knowledge of place is essential. The townland, one of the smallest and oldest surviving forms of land division in Ireland, forms the basis for all major Irish records: civil registration, census records, land records and, to a lesser extent, church records.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Not only do townlands serve as the foundation for most Irish genealogical research, they also hold a special place in the hearts of their inhabitants. According to Patrick Duffy, Professor Emeritus of Geography at Maynooth University, “for those born into townlands, first memories are rooted and never forgotten”. Despite being uprooted in later life, artists Patrick Collins and Tony O’Malley, who were raised in the Irish countryside, both retained a profound connection to the landscape of their childhood home, which manifested in their art.

According to official records, there are 61,098 townlands in the 32 counties of Ireland, which includes uninhabited townlands (mainly small islands). Historians generally agree that the townland framework, which had been established by the 12th century AD, inherited and maintained some earlier land divisions, such as those based on early medieval tribal septlands. Although boundaries often shifted over time, those defined by natural features, such as rivers and mountains, are likely original.

Sign up to our newsletter

Townland names

Most townlands can be categorized into two groups on the basis of their Irish names. The first group refers to natural features, either topographical or botanical. For example, “gleann”, meaning glen, in Glanmire (Gleann Maghair) and Glendalough (Gleann Dá Lach) or “saileach”, meaning willow tree, in Ardsallagh (Ard Saileach).

A F F I L I A T E A D

The second group refers to cultural elements, which are the product of human activity. For instance, “ceapach”, meaning plot of land or tillage plot, in Cappoquin (Ceapach Choinn) or ráth in Rathcooney (Ráth Chuanna) and Raphoe (Ráth Bhoth), which refers to a rath or ringfort – a type of early medieval settlement.

Also in the second group are the many townlands featuring the placename element “baile”, translated variously as home, place, land, farm or town, as in Ballymun (Baile Munna). The baile prefix, or a derivative of the word, appears in approximately one-tenth of all townland names.

Historical Irish texts indicate the existence of the baile from as early as the 11th century. For instance, the Annals of Ulster inform us that in 1011, Flaithbertach Ua Néill attacked Dún Echdach, now Duneight in Co. Down, burnt the fort (dún) and destroyed its baile. Additionally, according to one early poem, Ireland contained 184 trichaceds (trícha cét), each containing 30 baile biataigs, each of which, in turn, sustained 300 cows.

Not all baile townlands had their origin in the early medieval period as English influence on placenames began in the 12th century with the Anglo-Norman invasion. New placenames emerged, usually consisting of the Old English family name and the element “town” or “baile“. In Co. Cork, this is reflected in the townlands Piercetown and Ballincrokig from the Anglo-Norman families of Pierce and Croke.

Please help support

Irish Heritage News

A small independent start-up in West Cork

Give as little as €2

Thank You

The baile prefix is prolific in Ireland and geographer Patrick J. O’Connor has remarked on the flexibility of the baile placename, which seamlessly embraces various compounding elements, such as names of individuals or people (like Ballyphilip, Baile Philib or Baile Philip, meaning Philip’s town), land units or settlements (like Ballinoe, An Bhaile Nua, meaning new town), and topographical or botanical features (like Ballynahina, Baile na hEidhne or Baile na hAibhne, referring to the place of the river or the ivy-covered place).

The majority of names are of Irish-language origin, while others derive from English and Old Norse. For example, Fota Island, in East Cork, was recorded in 1573 as “Foty”, the “–y” ending in an island name indicating the probable Norse origin. The late Donnchadh Ó Corráin, a medieval history professor at University College Cork, believed that the name derived from the Old Norse “fódr oy”, meaning foot island, in reference to its position at the mouth of the River Lee between the mainland to the north and Great Island to the south.

In the 17th century, King Charles II remarked that the “barbarous and uncouth names of places in Ireland … much retard the reformation of the country”. Many English townland names, entirely disconnected from their earlier Irish names, were introduced between the 17th and 19th centuries. For example, the townland Cloch an Easpaig, meaning bishop’s stone, near Clonakilty in West Cork, had become “Ashgrove” by at least 1811.

The Down Survey

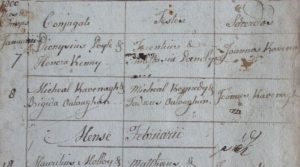

During the Down Survey, 1656–58, many Irish placenames were anglicized, with the names often translated as they were spoken. Referring to this process, the late district justice and antiquary Liam Price noted:

“English sounds being very different from Irish, many names have undoubtedly been corrupted beyond recovery in the process of anglicization.”

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

The Down Survey, directed by William Petty, physician-general to the English army in Ireland, was the first ever detailed land survey on a national scale anywhere in the world. The exercise sought to measure all the land to be forfeited by the Catholic Irish in order to facilitate its redistribution to English Protestant merchant adventurers and soldiers. This resulted in the first systematic mapping of Ireland with unprecedented levels of accuracy and uniformity.

The Down Survey of Ireland Project, led by Trinity College Dublin, began in 2011 and has its own dedicated website. Accessible on the site are digital images of all the surviving Down Survey maps at parish, barony and county level, with many recognizable townland names appearing on the maps. The maps also depict roads, rivers, towns, churches, castles and houses.

By comparing these maps to modern Ordnance Survey (OS) maps, we can see a fairly close correlation between many of the townlands of the 1650s and modern townland boundaries and names.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Also available on the Down Survey site are the written descriptions, known as “terriers”, that accompanied the original barony and parish maps. Much useful information can be gathered from these records. For instance, the terrier for the parish of St Finbarr’s (Finbarries / Finbarris) in Cork records that Thomas Gould owned 548 acres of arable land in the townland of Lehannaghmore, known today as Lehenaghmore. The surname Gould (from Gowlles) has been associated with Cork since the 15th century; several individuals bearing this surname held the position of mayor of Cork at least 30 times between 1442 and 1640.

Another component of the Down Survey website is the “Historical GIS”. It brings together other related contemporaneous sources – which includes information from the Quit Rent Office version of the Books of Survey and Distribution, the 1641 Depositions and the 1659 Census – in a Geographical Information System (GIS) that georeferences these sources with modern maps (OS, Google Maps and satellite imagery). This GIS allows you to search for landowners by name (1641 and 1670).

Logainm.ie

While the Down Survey website is an excellent primary source, many of the townland names have evolved over time and another website documents their evolution, citing each source for every instance of name change listed. The Placenames Database of Ireland, now more commonly known as Logainm.ie, is a comprehensive management system for the toponymic data, records and research of the Irish State.

Logainm.ie notes that the townland name of Newgrange, for example, derives from the Irish An Ghráinseach Nua, with “gráinseach”, meaning grange or monastic farm and “nua”, meaning new. Also included for each place are numerous scanned images of the original card indexes in which Irish scholars of the pre-digital age recorded meanings and spellings of the placename from historical sources; for each spelling recorded, the website also lists the source. The sources cited for the townland of Newgrange date from 1540 to 1836. A separate collection of resources on the site provides access to historical maps, accounts of the administrative structure of Ireland, and essays and manuscripts by placenames scholars.

Logainm.ie produces evidence of the complete transformation of Irish placenames when English speakers attempted to adapt the townland names to English phonetics and orthography. This process, as highlighted by Daithi Mac Carthaigh in a letter to the Irish Times, resulted in:

“place-names which had immediate resonance and which were rooted in local topography, history and environment … [being] reduced to meaningless collections of sounds.”

The townland name Ballinvriskig in Co. Cork demonstrates the mutation of toponyms over time. On Logainm.ie, its modern Irish name is recorded as “Baile an Bhrioscaigh” (elsewhere, it has been translated as “Béal Átha an Bhrioscaigh”). The second element of the placename, “an Bhrioscaigh”, could have its origins in the Irish term “briosc”, meaning light, easily broken-up soil.

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Alternatively, it could derive from “Brioscú”, an Irish translation for the English surname Briscoe – a family originally from Cumberland who settled in Ireland in the 12th century. (In fact, there is a village named Brisco, also known as Birksceugh, in what was formerly the historic county of Cumberland, now Cumbria.) The notebook of the OS field officers who surveyed Ballinvriskig townland in 1841 records the “received name” as “Briscoe’s town”.

The townland name has been spelt in a variety of ways over the centuries, but only some variants are recorded on Logainm.ie. “Ballyverskig” appears in the Civil Survey (1654–56), “Ballenvriskigg” with “Edward Gallwey gent” noted as titulado in the 1659 Census, and “Ballinbriskig” in the administration bonds from 1811. However, as Irish words beginning with “bh–” are pronounced like a “v” sound, and given that the earlier recorded spellings use a “v” at the start of the second element of the townland name, it may be that the name derived from “briosc” (with the genitive case being “an bhrioscaigh”) and not the family name Briscoe.

Sign up to our newsletter

In contrast, the etymology of the nearby townland of Sarsfield’s Court (Sarsfieldscourt) is much more straightforward. The surname de Sáirséil first appears in Ireland about the time of the Anglo-Norman invasion, when the family settled in Dublin, Limerick and Cork. In the 13th century, a member of the Sarsfield family secured a grant of land to be held in knight’s service to Barrymore (Sarsfield’s Court is in the barony of Barrymore).

During the 17th century, the fortunes of the family ebbed and flowed, and by the final years of that century, the fate of the Sarsfields was sealed when their land was forfeited and subsequently, in February 1703, the estate was purchased by Thomas Putland. According to historian and priest T.J. Walsh, all that remained of Sarsfield’s Court by 1953 was an ivy-clad ruin, which was situated on the lands of William O’Neill. Despite the crumbling façade, its Tudor character was then still visible as the stone-mullioned windows on the eastern side remained intact.

In the 1830s and 1840s, the OS standardized the anglicized spellings of all townlands, yet many persisted in using non-standardized spellings, including in official records and many people continue to use these non-standardized spellings up to the present day. This can present a challenge for genealogical researchers.

A F F I L I A T E A D

Administrative categorization of townlands

The key to Irish family history research lies in part in the name of the townland where your family lived. For example, townlands were ideal land divisions for facilitating the introduction of civil registration of non-Catholic marriages, which was enacted in 1845 and expanded to include all births, deaths and marriages in 1864. To ensure efficient management of civil registration, neighbouring townlands were grouped together to form a registrar’s district. Groups of these districts, in turn, were amalgamated, creating superintendent registrars’ districts.

Take, for example, Michael Collins, the Irish War of Independence leader: according to his birth record, he was born in the townland of Woodfield, in the district of Rosscarberry, in the union of Clonakilty, in the county of Cork. The 1901 census return for the Collins family places Woodfield in the district electoral division of Coolcraheen. Even more confusing for those researching their family history are the land records; for example, Griffith’s Valuation, from the mid-19th century, notes that Woodfield was in the (civil) parish of Kilkerranmore, in the barony of Ibane and Barryroe.

>>> RELATED: Who was Michael Collins’ mother? Mary Anne O’Brien explored

Griffith’s Valuation used the categories of townlands, civil parishes and baronies to tabulate the ownership and tenantship of land. (Check out my guide here for more information on Griffith’s Valuation.) Civil parishes are equivalent to the historic Church of Ireland parishes, which tend to more closely align with ancient land divisions than the Catholic parishes, which often amalgamated several civil parishes. Barony divisions may be pre-Norman but are occasionally later.

Thankfully, there are a number of websites that are essential for any genealogical research: Logainm.ie is a useful starting point to determine the electoral division, civil parish, barony, county and province where your townland of interest is located; this information and other categorizations can also be found in the Townland Index and here for the province of Munster. One thing to note is that present-day boundaries might not align with those used in the past for administrative purposes. (This useful table provides links for accessing further information on various types of land divisions.)

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

At the heart of all this research is the townland and Pat Loughrey rather aptly sums up their importance:

“Townland names, like the landscape to which they relate, are precious records of the history, legends and mythology of their communities [and] also contain keys to local history which are available from no other source.”

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

Fiona Forde, the Irish Family Detective, holds a diploma in genealogy studies and a master’s in local history from University College Cork. She teaches the family history programme at Ashton Adult Education, Cork and regularly presents to local history societies and community groups. You can visit her website here.

Advertising Disclaimer: This article contains affiliate links. Irish Heritage News is an affiliate of FindMyPast. We may earn commissions from qualifying purchases – this does not affect the amount you pay for your purchase.

READ NOW

➤ Stories behind common Irish surnames explored in new genealogy series, “Sloinne”

➤ A guide to navigating Northern Ireland’s church records

➤ Did your ancestor spend time in a workhouse?

➤ A genealogist’s guide to DNA testing for Irish family history research

➤ Tracing your roots online using old records of Irish gravestone memorials and “Mems Dead”

Notes:

The term “Old English” refers to people of Anglo-Norman descent who settled in Ireland from the 12th century, as distinct from the “New English” settlers who arrived during the 16th and 17th centuries.

The Down Survey obtained its name from the recurring use of the expressions “by the survey laid down” and “laid down by admeasurement”.

Sources:

Birth register, Michael Collins, born 16 Oct. 1890, registered 5 Nov. 1890, Union of Clonakilty.

[https://civilrecords.

irishgenealogy.ie/

churchrecords/images/

birth_returns/

births_1890/02404/

1896440.pdf]

Campbell, J. 1987. ‘Patrick Collins and “the sense of place”’. Irish Arts Review 4.3, p.48.

Census of Ireland, 1901, Collins household, house 19 in Woodfield, Coolcraheen, Cork.

[http://www.census.

nationalarchives.ie/

pages/1901/Cork/

Coolcraheen/Woodfield/

1162061/]

Down Survey of Ireland,

[https://downsurvey.

tchpc.tcd.ie/index.html].

Duffy, P. 2004. ‘Townlands: territorial signatures of landholding and identity’. In B. S. Turner (ed.) The Heart’s Townland: marking boundaries in Ulster. Downpatrick, p.20.

Griffith’s Valuation, Woodfield, parish of Kilkerranemore.

[https://griffiths.askaboutireland.ie/

gv4/z/zoomifyDynamicViewer.php?

file=053050&path=./pix/053/

&rs=53&showpage=1&mysession

=2895400219334&width=&height=].

Loughrey, P. 1985. ‘Communal identity in rural Northern Ireland’. Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review 74.295, pp.307-08.

Mac Carthaigh, D. 1999. ‘Restoring Irish place-names.’ Irish Times, 1 Sept. 1999.

[https://www.irishtimes.com/

opinion/letters/

restoring-irish-place-names

-1.222547]

MacCotter, P. 2008. Medieval Ireland: territorial, political and economic divisions. Dublin.

McErlean, T. 1983. ‘The Irish townland system of landscape organisation’. In T. Reeves-Smyth and F. Hammond (eds) Landscape Archaeology in Ireland. British Archaeological Reports (British Series) 116, Oxford, pp.315-39.

O’Connor, P. J. 2001. Atlas of Irish Place-names. Newcastle West, p.21.

Ó Corráin, D. 1997. ‘Note: Old Norse place names I: Fodri, Foatey, Fota’. Peritia 11, p.52.

Ó Murchadha, D. 1959. ‘Where was Insovenach?’. Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society 64.199, p.61.

Ordnance Survey Ireland. ‘Townland’.

[https://data.gov.ie/

dataset/townland?

package_type=dataset]

Petty, W. 1851. The History of the Survey of Ireland, Commonly Called “The Down Survey”, A.D. 1655-6. T. A. Larcom (ed.) Dublin, pp. vii, 326.

Placenames Database of Ireland,

[https://www.logainm.ie/en/].

Price, L. 1951. ‘The place-names of the Books of Survey and Distribution and other records of the Cromwellian settlement’. Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland 81.2, p.94.

Seebohm, F. 1914. Customary Acres and Their Historical Importance. London, p.49.

Wilson, J. M. 1870. The Imperial Gazetteer of England and Wales. Vol. 1. Edinburgh, p.275.

2 Responses

Thank you very much for this wonderful newsletter, the content is always of great interest and the writing is excellent, I enjoy it immensely every time.

I’ve just discovered this site and am excited to see more!